Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

We're Still Here, Part 3: The San Fernando Valley

Because it IS my home. I'm a genuine, authentic Valley girl (hang around me long enough and you just might detect bits of my old accent).

(Well, it was my childhood home, anyway. I've lived in various beach towns continuously since 2001.)

Let's start in Calabasas and work our way east...

Michel Leonis, nicknamed "Don Miguel" out of fear rather than respect, discovered a dilapidated adobe house on the grounds of Rancho El Escorpion (huge naming opportunity missed here: Rancho El Escorpion sounds so much more badass than Calabasas - Spanish for "squashes"). He and his Chumash wife, Espiritu Chijulla, fixed it up (enclosing the rear staircase and adding the balcony), moved in, and lived here until their respective deaths.

The house - long empty and once again severely neglected - was nearly torn down in 1962 for - you guessed it - a supermarket parking lot. Thankfully, it's still with us today.

(I will devote separate entries to Leonis and to the Leonis Adobe Museum.)

Moving east, we find...

Running north-south from Ventura Boulevard to Granada Hills (okay, fine, it's interrupted in a couple of places), Amestoy Avenue was named for another French Basque ranching family - the Amestoys.

(The Amestoys will get their own entry.)

Just a few blocks east of Amestoy Avenue is one of their former homes - Rancho Los Encinos.

Four French and French Basque families - Garnier, Oxarat, Gless, and Amestoy - owned the rancho in turn. The original adobe is on the right. The two-story house on the left was built by the four Garnier brothers to house the rancho's employees, and is said to be a copy of the family home in France.

Although slightly beyond the scope of this entry, but worth noting, is the fact that Eugene Garnier once testified against Michel Leonis in court. Leonis, a brutal and terrifying thug who added to his vast land holdings through harassment and intimidation, burned the Garniers' newly planted wheat field and beat their employees. Eugene stated in court that he was testifying only because he was forced to do so, and later returned to France. His brother Philippe Garnier, bloody but unbowed, went on to build the Garnier Building and lease it to Chinese tenants.

I include this photo as proof that culture and beauty do, in fact, exist in the Valley if you know where to look. The Garnier brothers were legendary for their hospitality - so much so that Pio Pico's brother Andrés used to bring very special guests all the way to Rancho Los Encinos (from what is now downtown) - ON HORSEBACK. For BREAKFAST.

And those very special guests dined in the Garniers' grand salon, which boasted the most striking faux marbre walls in the history of Los Angeles. (I hope someone else takes the time to notice that the plastic food on the table is French in theme - grapes, brie, asparagus, and crusty-looking bread.)

At some point, an incredibly foolish individual elected to plaster over the faux marbre. The adobe was severely damaged in the Northridge earthquake of 1994, but with one silver lining - much of the plaster covering the salon's elaborately painted walls fell off. (Portions of the offending plaster remain. This is a very delicate old house, and that paint is well over 100 years old. Some things are best left well enough alone.)

(All four families merit, and will get, their own entries. Ditto Los Encinos State Historic Park, where the adobe and the ranch hands' quarters are located.)

The Amestoy family - the last French owners of the rancho - held onto much of the land (including these buildings) until 1944. After World War II, Rancho Los Encinos was subdivided into (what else) Encino and (my neck of the woods) Sherman Oaks.

On a personal note, my mother was completely shocked to learn that the Los Encinos adobe was a) still standing, b), continuously French-owned for much of its existence, c) right above Ventura Boulevard (a thoroughfare my family knows pretty well), and d) less than six miles from our old house in Sherman Oaks. She's said that if she had ANY idea, she would have taken me there when I was a child (in addition to Olvera Street, Chinatown, etc.).

Moving further east...

A street in Mission Hills was named for onetime mayor Joseph Mascarel. I suspect he owned land in the area (he owned significant amounts of land in FOUR counties). Today, he is so little-known that whoever made this sign didn't bother to check the spelling.

Heading further east...

Solomon Lazard was both French and Jewish, and was so popular with Angelenos of all ethnicities that he was nicknamed "Don Solomon" and often acted as floor manager for fandangos. He was the first President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, co-founded the City Water Company (later LADWP) with Prudent Beaudry and Dr. Griffin, founded the City of Paris department store (which he later sold to his cousins, Eugene and Constant Meyer), and was active in the Golden Rule Lodge and the Hebrew Benevolent Society. Today, he's been reduced to a street sign on a cul-de-sac in San Fernando. (There was a different Lazard Street long ago, and Mayor Mascarel lived there until his death. It was renamed Ducommun Street. I'll explain why when I get to Charles Ducommun.)

Heading even further east, we reach our final stop in the furthest reaches of Glendale...

You know who Georges Le Mesnager was. This stone barn was built for his vineyard, located in what is now Deukmejian Wilderness Park. When it was damaged in a fire, his son converted it into a farmhouse - which the family lived in until the 1960s.

The barn has been undergoing a remodel/conversion into an interpretive center.

I knew nothing about any of these places until I began to research LA's forgotten French history - and one of them was just a few miles from my house. Small wonder that most Angelenos have NO idea about Frenchtown.

Sunday, August 6, 2017

We're Still Here, Part 3B: Rancho Los Encinos

Philippe Garnier, Gaston Oxarat, Simon Gless, and Domingo Amestoy.

Former residents. Note the prevalence of Basque surnames.

The original de la Osa adobe house. This is the second oldest structure in the Valley - and the only one that is pretty much unaltered.

Philippe Garnier's shaving stand.

Gaston Oxarat's saddle. This finely tooled piece was originally covered with tiny silver conchas (shells).

Juanita Amestoy wore this beautiful gown when she married Simon Gless.

Don Vicente de la Osa had previously turned the adobe into a stagecoach stop and roadside inn. The Garnier brothers, being from France, kicked the hospitality up a notch.

The Garniers had one of the adobe's rooms painted with beautifully detailed faux marbre panels.

Can you believe some idiot PLASTERED OVER these stunning walls? For over a century, no one knew this fine paint job was even there.

Try, if you can, to let your imagination fill in the blanks. It's a beautiful room now - it must have looked even better then.

The Northridge earthquake of 1994 severely damaged the adobe (one outer wall caved in, requiring extensive repairs). However, there was one silver lining: the earthquake may have damaged the house, but it shook much of the offending plaster right off the salon's walls. As you can see, some of the faux marbre is still covered by plaster. There is a good reason for this: the adobe is very old and very delicate. Some things are best left alone, even if they're not perfect.

What's that next to the adobe?

Sunday, March 1, 2020

The Crazy Life of Rémi Nadeau

Anglos called him "the crazy Frenchman". French Angelenos called him "crazy Rémi".

Was he really crazy? Was he hypersane? Or was he an eccentric visionary with a head for business?

We may never know the answer. But we do know his big dreams and "crazy" ideas made him rich.

Rémi Nadeau moved to Los Angeles in 1861. He quickly settled into the local French community - and secured a $600 loan from Prudent Beaudry.

With that loan, Rémi bought a wagon and a team of mules and set up his own freighting company.

Initially, Rémi made supply runs to faraway Salt Lake City - which took more than a month each way in those days. Harris Newmark reported that Rémi spent a few years in San Francisco, returning in 1866.

Rémi owned an entire city block - the same one where the Millennium Biltmore Hotel now stands. In his day, the land held his house, a stable, a corral, and a blacksmith shop.

Rémi's reputation as an eccentric was well earned: the Nadeau family's housekeeper wasn't allowed to clean the master suite. Mrs. Nadeau would do it herself. One day, when Mrs. Nadeau had fallen ill, Rémi's young niece Melvina Lapointe came over to help with the cleaning. While dusting, Melvina came upon a vase of fake flowers that seemed unusually heavy for its size. She pulled several wads of yellowed newspaper out of the top of the vase. To her surprise, the vase was filled with gold pieces! Mrs. Nadeau came into the room and instructed Melvina to put the vase back EXACTLY as she had found it so Uncle Rémi wouldn't change the hiding place.

In 1869, Rémi landed a very desirable contract: hauling silver and lead ore from the Cerro Gordo mines (near Lake Owens) to the Port of Los Angeles, where they would then be sent to San Francisco via ship for refining. (One of the partners in the Cerro Gordo mines was, of course, Victor Beaudry.)

The land in between Cerro Gordo and Los Angeles was rough, uninhabited, and in those days, devoid of roads. Rémi developed a large, heavy wagon with wide metal wheels that would be pulled by teams of twelve or more mules (depending on the load, twenty or more mules might pull a single shipment). The mines produced so much bullion that Rémi soon had 32 mule teams making regular runs to Cerro Gordo.

To maximize profits, Rémi sent the wagons to Cerro Gordo loaded with grain and other provisions. These would be sold to the miners, and the wagons would be reloaded with silver ingots for the return trip to San Pedro.

The owners of the Cerro Gordo mines demanded a reduction in freighting fees when Rémi's contract expired in 1871. Believing no one else could handle the task as well as his employees, he refused.

Barley prices had risen, and feeding hundreds of mules became very expensive. Rémi had taken out a loan from H. Newmark and Company to expand. Uncertain of his ability to pay the balance, he offered to turn over the freighting business to them. The company, believing in Rémi's ingenuity, encouraged him to find another contract instead.

Surely enough, a new opportunity soon arose when large deposits of borax were discovered in Nevada, and Rémi landed the contract. Boxes of 20 Mule Team Borax still reference Rémi's mule teams to this day.

When Rémi refused to renew his contract at a low rate, the mine owners had to route the silver bullion through other freighters in San Buenaventura (Ventura) and Bakersfield. Neither town could handle the output, and silver ingots began to pile up.

The Los Angeles business community wanted the silver trade back (it was the town's biggest moneymaker at the time), and tried to negotiate with the Southern Pacific Railroad - which announced a raise in freighting rates that would have made the plan too expensive.

Finally, the mine's owners (and the newly formed Chamber of Commerce) had to eat their humble pie and work out a fair contract with Rémi. He agreed to resume freighting silver bullion - on the condition that the mine's owners put up $150,000 to build freighting stations along his routes.

The Cerro Gordo Freighting Company soon had 65 stations ranging from San Pedro to Nevada to Arizona to San Francisco. Each station was a combination of hotel, trading post, blacksmith shop, and wagon repair shop, with stables and corrals for mules. Nadeau eventually had over 300 employees, and was so busy he put his brother-in-law, Michel Lapointe, in charge of the wagon works.

If you don't mind a 275-mile drive, Cerro Gordo is now open for tours (reservations required).

Some of the freighting stations grew into towns. In fact, one of them became the desert suburb of Indian Wells.

Eventually, railroads began to stretch across the Mojave Desert, reducing demand for mule teams. The Cerro Gordo Freighting Company sold off its mules and equipment, and Rémi began his next enterprise.

During the brief period of time that the Nadeau vineyard existed, it was believed to be the largest vineyard in the world.

Rémi also planted barley on the Centinela Rancho (modern-day Inglewood)...until extreme heat and a drought put an end to the barley crop.

In the 1880s, the Plaza and surrounding streets were still the city's primary business district. Rémi bought land at First and Spring Streets, and even Harris Newmark - Rémi's close friend and greatest supporter, who knew firsthand how smart and capable he was - called him crazy for buying land so far from the Plaza.

As per usual, Rémi didn't care what anyone else thought.

Initially, he planned to build a grand opera house or theatre with 1500 seats. (Even I think that was a crazy idea, considering Los Angeles' 1880 population was less than 12,000.) But that idea gave way to the city's tallest and grandest building of the era - a four-story business block, equipped with Southern California's first passenger elevator (made by Otis) and four fire hydrants on each floor, with apartments and office spaces planned for the upper floors and storefronts planned for the ground floor. No expense was spared, and the building was even equipped with twenty bathrooms - a VERY high number of bathrooms for the time.

Everyone laughed.

Everyone called the plan "Nadeau's folly."

Everyone said Rémi Nadeau, the crazy Frenchman, was crazier then ever.

Then "Crazy Rémi" leased the entire building to Ed Dunham, an experienced hotelier.

And just like that, everyone who was anyone checked into the Nadeau Hotel when they stayed in Los Angeles. It was the first truly first class hotel in the city. (Sorry, Pio Pico, but the Pico House didn't have an elevator, let alone twenty bathrooms.)

Sadly, it would be the final time Rémi got the last laugh. Less than a year after the Nadeau Hotel's 1886 grand opening, he passed away at age 68.

Rémi left the hotel property to his second wife, Laura, along with enough money to pay off its mortgage so she wouldn't have to come up with payments. His children from his first marriage (to Martha Frye) felt this was too generous a bequest for their stepmother and contested the will (sound familiar?).

The Nadeau Hotel was torn down in 1932 for the Los Angeles Times building.

Laura Nadeau decided to honor Rémi's memory with a 30-foot-high monument, topped with a marble statue of an angel, at the Nadeau family plot in Angelus Rosedale Cemetery.

Unfortunately, the Nadeau family plot happens to be very close to a rather large mature tree. Several years ago, according to a docent (who couldn't pronounce "Nadeau" correctly, plainly stated that she didn't know what Rémi did for a living, and rudely blew me off when I mentioned that he was a freighter...), a particularly windy rainstorm sent a very heavy tree branch crashing right onto the Nadeau plot. Every time I've visited Angelus Rosedale, a large and heavy chunk of monument has been in the same spot on the ground at a cockeyed angle. I was told that Rémi's living relatives couldn't justify the high cost of having it repaired. I get it - stonework is expensive.

When the monument was unveiled, the Los Angeles Herald claimed that Rémi's own accomplishments were the only monument needed to keep his memory alive. Rémi’s business interests accounted for ONE QUARTER of all exports leaving Los Angeles between 1869 and 1882. An earlier article in the Herald claimed Nadeau “has given employment to more men, and purchased more produce, and introduced more trade to Los Angeles than any other five men in this city.”

You'd think that would be enough. Sadly, you'd be as mistaken as the Herald.

Rémi's name is forgotten today, surviving only in the family plot and on street signs - Nadeau Street, in the Florence/Nadeau neighborhood, and Nadeau Drive (which most likely honors Dr. Hubert Nadeau, no relation), in Mid-City.

Now THAT is crazy.

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

He Built This City: Mayor Prudent Beaudry

Possessing boundless energy, exceptional business sagacity and foresight, Prudent Beaudry amassed five fortunes and lost four in his ventures, which were gigantic for that time, and would be considered immense today.

Have a seat, everyone...the lifetime I'm chronicling this week is best described as "epic".

Jean-Prudent Beaudry was born July 24, 1816 in Mascouche, Quebec - close to Montreal. When he was a young boy, the family moved to the neighboring town of Saint-Anne-des-Plaines.

There were five Beaudry brothers (and three Beaudry sisters). All of the Beaudry brothers worked hard and got rich, but Prudent, Jean-Louis, and Victor would make the history books. (Victor, the only other Beaudry to settle in Los Angeles, will be covered in another entry, because this one is going to be LONG.)

The Beaudrys, an industrious family of traders, sent their sons to good schools in Montreal and New York. Prudent and his brothers had the benefits of a great education and English fluency when they went into business for themselves.

Which they did, many times over.

Prudent started out in his father's mercantile business, then went to work at a different mercantile house in New Orleans, returning to Canada in 1842 to partner with one of his brothers. By 1844, he left the business to join Victor, the youngest Beaudry brother, in San Francisco. The Gold Rush was a few years away, but Victor had already established a profitable shipping and commission business in the city. Before long, the brothers were in the ice business (Victor later partnered with another future mayor, Damien Marchesseault, in distributing ice harvested in the San Bernardino Mountains). Perhaps not surprisingly for a native of Quebec, Prudent also got into the syrup business. Two years later, after Prudent had lost most of his money on real estate speculation (and more of it when insufficiently insured stock was destroyed in a fire), Los Angeles beckoned.

I'll let Le Guide Francais take it from here:

Starting with $1,100 in goods and $200 cash in a small store on Main Street, where the City Hall now stands, it is said that he cleared $2,000 in thirty days, which enabled him to take a larger store on Commercial Street. From that time on, Prudent Beaudry was one of the preeminent men of the economic, social, and political life of the Southwest.(The book, just to clarify, refers to the current City Hall, not the old Bell Block down the street. After Beaudry vacated the Commercial Street shop, Harris Newmark moved in. Ironically, Beaudry sold his dry goods business to Newmark twelve years later.)

Having earned a well-deserved vacation, Prudent left Los Angeles for Paris in 1855. The chief items on his itinerary were seeing the Exposition Universelle and consulting the great French oculist Dr. Jules Sichel. Prudent visited Montreal on his return trip to visit his brother Jean-Louis, who would serve as Mayor of Montreal for a total of ten years between 1862 and 1885. The Beaudrys, needless to say, were just as prominent in business, politics, and society in Quebec as they were in Southern California.

While Prudent was away, Victor was capably managing his brother's business interests. Prudent had purchased a building on the northeast corner of Aliso and Los Angeles Streets in 1854 for $11,000. Victor spent $25,000 - an absolute fortune at the time - on remodeling and improving the building. In this case, it was money well spent. After the Beaudry Block was improved, it was considered the finest building in Southern California for the time. Rents increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Prudent returned to Los Angeles in 1861 (Victor had been offered a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and found it difficult to manage his brother's business interests at the same time). He continued in the mercantile business until 1865. Due to stress, he retired...but not for long. The Beaudrys just weren't capable of being unproductive.

In 1867, Prudent Beaudry made one of his greatest real estate investments. The steep hill above New High Street, which he purchased at a Sheriff's Department auction for the pittance of $55 (I can't believe it either), was known as Bunker Hill. It would soon become famous for its Victorian mansions.

This purchase set Beaudry on a path that made him California's first realtor and first large-scale developer, in addition to an urban planner. Before long, he was buying extensive tracts of land, dividing them into lots, and selling them, working out of an office opposite the Pico House. One 20-acre tract, between Charity (Grand) and Hill from Second to Fourth, cost $517 and netted $30,000. Another tract, consisting of 39 acres bordered by Fourth, Sixth, Pearl (Figueroa) and Charity (Grand), earned $50,000.

The Beaudry brothers (smartly) kept buying land. They predicted - correctly, and beyond their wildest dreams - that after railroad lines connected Los Angeles to San Francisco and the East Coast, new settlers would pour into Southern California in droves. (If they could only see how right they were!) Prudent also bought land in modern-day Arcadia and near the Sierra Nevada mountains (building aqueducts to redirect mountain streams to his properties), and helped to found the cities of Pasadena and Alhambra.

One newspaper advertisement from 1873 lists 83 (yes, 83!) separate lots for houses, in addition to two full city blocks, multiple city tracts, and large land parcels in Rancho San Pedro, Verdugo Ranch, and the Warner and de la Hortilla land grants. A similar ad from 1874 notes, in bold, which of the streets with lots for sale had already had water pipes installed. It's no wonder Beaudry was able to keep his real estate business going every time he lost most (or all) of his money.

Severe flooding in January 1868 had undone nearly all of Jean-Louis Sainsevain and Damien Marchesseault's hard work on the city's primitive water system. As a developer, Beaudry was very concerned about improving the city for its residents. On July 22, 1868, a 30-year contract for the water system was granted to the newly-established Los Angeles City Water Company. The three partners in the Company were Dr. John Griffin, French-born businessman Solomon Lazard, and, of course, Prudent Beaudry (most of the employees were also of French extraction - chief amongst them, Charles Lepaon, Charles Ducommun, and Eugene Meyer - more on them in the future).

The Los Angeles City Water Company replaced Sainsevain and Marchesseault's leaky wood pipes with 12 miles of iron pipes, and continued to regularly make improvements on the water system until the contract expired 30 years later (the city purchased the system for $2 million - in 1898 dollars!). Although nothing could cancel out the previous water problems or Marchesseault's tragic suicide, the city of Los Angeles finally had a reliable water system that wouldn't turn streets into sinkholes. (If you live in Los Angeles and you like having running water, thank a Frenchman. Seriously, you guys owe us.)

You're probably wondering how Prudent managed to supply water to his hilltop property. In those days, hills weren't desirable places to build homes because water had to be transported in barrels via trolley or other vehicle. The city water company wasn't interested in solving the problem. But in case you haven't noticed yet, Prudent was smart, resourceful, and didn't give up easily. He knew that if running water was available, prospective homeowners would be more likely to consider hilltop lots and pay a good price for them. So he constructed a huge reservoir and a pump system that supplied water from LA's marshy lowlands to Bunker Hill. The pump system worked perfectly - and so did his plan. (I'll bet every land speculator in Southern California wished they had thought of that.)

Before long, Bunker Hill became THE place to build grand homes. At least two of its fabled Victorian mansions were built for other French Angelenos - entrepreneur Pierre Larronde and model citizen Judge Julius Brousseau.

Let it be known, however, that Beaudry developed for everyone. It's true that he built mansions and had a keen interest in architecture, but he also built modest homes on small lots for working families. And because he made modest properties available for small monthly payments, he made home ownership possible for buyers with lower incomes. He made considerable improvements to his land - paving roads, planting trees, and providing for water usage.

And Beaudry just kept developing land for the rest of his life. This Lost LA article includes an 1868 map showing five tracts recently developed by Beaudry.

The Bellevue tract included a garden he dubbed "Bellevue Terrace". This early park rose 70 feet above downtown, boasting hundreds of eucalyptus and citrus trees. Beaudry eventually put the site up for sale. The State of California bought it to develop a Los Angeles campus of the State Normal School, which would later become UCLA. When UCLA moved to Westwood in the 1920s, the hill was graded down and replaced with Central Library.

A few miles away, where North Beaudry Avenue meets Sunset Boulevard, there is an oval-shaped parcel of land that currently holds a church, a restaurant, and The Elysian apartment building. In the early 1870s, this was Beaudry Park - another garden paradise on a hill, boasting citrus groves and eucalyptus trees (and vineyards!). But the Beaudrys put it on the market a decade later. The Sisters of Charity snapped it up in 1883, building a newer facility and relocating St. Vincent's Hospital (sometimes called the Los Angeles Infirmary) here.

Beaudry owned a large tract containing one block of stagnant, foul-smelling marshland. No one wanted to build on the land, and it wasn't ideally suited to building anyway. In 1870, Beaudry got the idea to drain the marsh and turn the land into a public park. Naturally, he spearheaded the plan. Originally called Los Angeles Park, the land was renamed Central Park in the 1890s...and was renamed again later.

You know this park. There's a good chance you've been there (and there's a VERY good chance you absolutely hate its current incarnation).

Give up yet?

It's Pershing Square. (It used to be a very nice park. Trust me on this.)

Beaudry's dedication to developing, planning, and improving the city got him started in politics. He was elected to the Los Angeles Common (City) Council for three one-year terms (1871, 1872, and 1873). In 1873, he became the first president of the city's new Board of Trade. His name appeared in Los Angeles newspapers frequently throughout the 1870s and 1880s - mostly in the real estate sections (and in a bankruptcy case...the Temple and Workman Bank failed and took most of his money with it).

In 1874, Prudent Beaudry became Los Angeles' third French mayor, serving two terms. At the same time, his brother Jean-Louis Beaudry was serving as mayor of Montreal.

After finishing his second term, Beaudry bought the local French-language newspaper, L'Union. (I will cover LA-based French newspapers - three or four are known to have existed - at a later date.) Beaudry was already a director of the Los Angeles City and County Printing and Publishing Company.

Nearly all of Los Angeles' Victorian houses have been torn down over the years. However, neighborhoods like Angelino Heights still have Victorian-era homes. Guess who developed Angelino Heights? That's right - Prudent and Victor Beaudry (architect Joseph Newsom designed many of the houses). Carroll Avenue, beloved by preservationists for its high concentration of surviving Victorian homes (kitsch king Charles Phoenix even includes it on his annual Disneyland-themed DTLA tour as "Main Street USA"), is well within the original boundaries of Angelino Heights.

In the 1880s, Angelino Heights was one of LA's earliest suburbs. Cars would not be commonly used for quite some time. To serve the transit needs of potential home buyers, the Beaudry brothers (with several other real estate promoters) built the Temple Street Cable Railroad. This streetcar ran along Temple Street from Edgeware to Spring (it was soon extended to Hoover Street) every ten minutes and ran for 16 hours each day, making transportation fast and simple for residents of Angelino Heights and Bunker Hill. The Pacific Electric Railway eventually purchased the line (switching from cable cars to electric trolleys in 1902), and in time it passed to the Los Angeles Railway. The Temple Street Cable Railroad - far and away the most successful streetcar line in the city's history - ran from 1886 to 1946. SIXTY YEARS. Which is especially impressive considering the Pacific Electric Railway didn't even exist until 1901, and its less-traveled streetcar lines were converted to bus routes in 1925.

Funnily enough, Beaudry had sued the Los Angeles Railway in 1891. He claimed the Railway had excavated First and Figueroa Streets without the proper authority, rendered the streets useless, and blocked access to his property. (He also occasionally sued people who damaged his properties. Can you blame the guy? Building a city is hard work.)

When "Crazy Remi" Nadeau decided to liquidate most of his freighting company's equipment, it was purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company...which counted Prudent and Victor Beaudry among its shareholders. In the 1880s, the Beaudrys began to take on fewer and fewer projects, but they both remained vocal supporters of developing and improving Los Angeles.

Prudent Beaudry passed away on May 29, 1893, a week after suffering a paralytic stroke (Victor had passed away in 1888, with Prudent acting as executor of his sizable estate). An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County stated:

Prudent Beaudry, in particular, has the record of having made in different lines five large fortunes, four of which, through the act of God, or by the duplicity of man, in whom he had trusted, have been lost; but even then he was not discouraged, but faced the world, even at an advanced age, like a lion at bay, and his reward he now enjoys in the shape of a large and assured fortune. Of such stuff are the men who fill great places, and who develop and make a country. To such men we of this later day owe much of the beauty and comfort that surround us, and to such we should look with admiration as models upon which to form rules of action in trying times.Beaudry died a wealthy man (despite losing his fortune FOUR times), but ironically, he might have died even wealthier. A 1905 article in the Los Angeles Herald stated that nearly forty years previously (i.e. in the 1860s), he had begun to dig a well on one of his hilltop properties. After several hundred feet, he struck a deposit that "looked and smelled like tar." He promptly abandoned the half-dug well. That's right - Beaudry struck oil. But he wasn't looking for oil and had no use for it. Had he made the same discovery a few decades later, things may have been a little different.

The late Mayor's body was returned to his native Quebec. Like the rest of his family, he is buried at Notre Dame des Neiges (Canada's largest, and arguably most beautiful, cemetery). He never married and had no children, so his estate went to the other Beaudry siblings and their families.

Prudent Beaudry's importance as an urban planner and city developer is almost completely forgotten today. His work lingers in the names of Beaudry Avenue, Bellevue Avenue, and various other French-named streets in tracts he developed long ago. (Hill Street was once called Montreal Street in honor of the brothers' hometown - it isn't clear when it was renamed.)

(And, thankfully, Angelino Heights is still standing. I will lose my last remaining shreds of faith in humanity if something bad happens to those precious few surviving Victorians.)

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Early French Restauranteurs of Los Angeles: Victor Dol

Friday, January 12, 2018

Something is Rotten in Frenchtown

I strive to do that on this blog (barring the musical interludes).

I *could* petition the city of Los Angeles to turn a weedy vacant lot in the industrial core (formerly the original French Colony) into a French-themed tourist attraction à la Olvera Street...but I am not Christine Sterling and I don't think it's the best possible answer. There are still authentic surviving sites associated with the French in Los Angeles, and at least one of them would make a great museum.

And history museums, unlike tourist attractions, are expected to present the truth.

I've uncovered some uncomfortable truths in the course of my research (and the more research I do, the more I cringe at all of this):

- Seemingly reliable resources can conflict with each other. There are things I haven't blogged about yet because I'm not yet sure which version of a story is correct (and unlike some people, I actually care about getting the facts straight).

- The city of Los Angeles itself is an unreliable source at best. The most glaring example: Damien Marchesseault was elected Mayor SIX TIMES. He was one of LA's most popular mayors of all time. Yet, he does not appear on the city's official list of former mayors, and the memorial plaque in the Plaza that bears his name includes incorrect information (two months ago, the venerable Jean Bruce Poole had me take her to the marker and show her what was wrong with it). He has been erased from LA's narrative so thoroughly that we don't even know what he looked like (no surviving pictures have ever been found). The fact that Marchesseault Street is slated for a return to the map is nothing shy of a miracle. (Part 2 of that story coming soon.) Was Marchesseault erased by political rivals after his death, or was he forgotten so readily because his final term ended under an ugly storm cloud of scandal and suicide? (I'm going to find out. I'm not sure how, but I know I'm going to do it.)

- Wikipedia can bite me. In spite of the fact that it's a nightmare to edit, anyone can edit Wikipedia, and it's just too easy for someone with incorrect information (or worse, an agenda) to misinform anyone gullible enough to take the site's content at face value. Example: The last time I checked, the site claimed that LA's New Chinatown was previously Little Italy. While there were significant numbers of Italian immigrants in the neighborhood, the article fails to note that it was part of Frenchtown first. In fact, that's WHY Italians were attracted to the area. LA's French welcomed Italian immigrants - two founding members of the French Benevolent Society were, in fact, Italian. St. Peter's Church, long linked to LA's Italian community, was originally a cemetery chapel built in honor of French-born André Briswalter (the current building is from the 1940s, and it isn't clear if Briswalter is still buried on the site). And the various French-owned vineyards already clustered in the area would have spelled job opportunities to Italian immigrants with winemaking skills. No one talks about any of this (except me)...yet the vast majority of people reading that entry are going to take it at face value (in spite of the fact that to local historians, it is glaringly incomplete).

- LA's various French organizations (and the French consulate) have never responded to any of my requests for information and/or interviews. At one point, I even asked my dad if his boss would mind sending my contact information to the consulate through a French government employee he knows (the French are formal; we like introductions). Yeah...that didn't work either. (I've had many a question about why I have yet to publish anything on current French entities in LA. Now you know. I'm used to being ignored - but not by people/organizations with whom I have a shared goal. It's indescribably frustrating.)

- I'm ALREADY getting pushback on my idea for a museum. Someone I met recently very pointedly told me (more than once!) that the Pico House hosted an exhibit on the French in LA "a couple of years back". That exhibit ran from late 2007 to early 2008 - TEN years ago. Also, it ran for less than six weeks, wasn't well executed (photos on a wavy plastic wall with no physical exhibits? Are you kidding me? The French are responsible for some of the finest museums in the world...we can do SO much better than that), and has been forgotten by pretty much everyone else. I realize getting a museum open can easily take 10+ years, cost an absolute fortune, and require dealing with a lot of red tape (the Historic Italian Hall Foundation, which was founded to restore the Italian Hall and reopen it as a museum, was founded in the 1980s...and the museum opened in 2016). But, given what we're constantly up against, shouldn't historians and other concerned Angelenos work together to keep the rare surviving scraps of Old Los Angeles alive instead of writing off ideas that don't necessarily fit into a personal agenda?

- I keep finding factual errors in other historians' work. I don't want to diminish the importance of their research and accomplishments. I really don't. However, LA's forgotten French community was filled with amazing people who did amazing things, and I believe we owe it to them to AT LEAST tell their stories correctly.

P.S. In the meantime, I'm speaking at StaRGazing 2018, Greater Los Angeles Area Mensa's annual Regional Gathering. I'm scheduled for 3:20-4:40pm on Saturday, February 17. See you in San Pedro! (Get your ticket NOW. Seriously.)

Friday, August 31, 2018

Felix Signoret: Barber, Councilman...and Vigilante

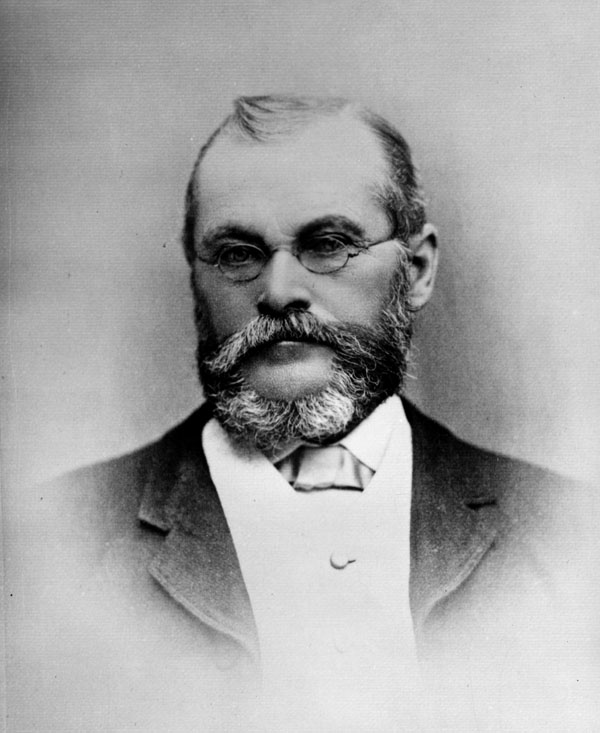

|

| Felix Signoret |

Regular readers may recall that, two years ago, I wrote about the violent life and death of Michel Lachenais. Today, we meet the leader of the lynch mob that finally put a stop to his misdeeds. (Beret-tip to reader Bob Edberg, who referred me to this picture.)

Felix Signoret was born June 9, 1825 in Marseilles, France. He arrived in California in 1856, becoming a naturalized citizen a year later, and married Paris-born Catherine Pazzan in 1858. They had five children - Rosa, Anne, Caroline, Louise, and Felix. Tragically, baby Felix only lived for a month. Louise fared little better, passing away at four months of age.

For some time, the only barber in Los Angeles who catered to non-Spanish clients was Peter Biggs. Although Biggs was clever and entrepreneurial, he had no talent for cutting hair. When Signoret, a massive, ham-fisted man who happened to be a very good barber, set up shop in town, Biggs initially reduced his prices and wound up changing jobs.

Signoret established a fine barbershop and invested his earnings in a saloon, billiard hall (LA was still the Wild West, after all), and in time, his own business block. Per the ads in the Jan. 5, 1876 edition of the Los Angeles Herald, tenants included multilingual physician Dr. J. Luppo and V. Chevalier's French drugstore (we'll meet Chevalier again later). Signoret Block, with hotel rooms on the upper floors and retail space at street level, opened in 1874 and stood at 15 Main Street opposite the Pico House. It boasted brick construction (which was not cheap) and - something very rare for Los Angeles - a mansard roof.

|

| Signoret Building |

|

| 1876 view of Main Street. Signoret Building on the right. |

Signoret was elected to the Common Council (now the City Council) in 1863 and served on the County Board of Supervisors in 1866. Oh, and he was also very active in the local Vigilance Committee. At one point, he even threatened to hang two attorneys who frequently secured acquittals for murderers.

Let me be VERY clear: I DO NOT condone vigilante justice. Due process of law exists for good reasons, and vigilantes have killed innocent people. That said, there is a reason someone like Signoret would join the Vigilance Committee in the first place.

Early Los Angeles was pretty much lawless. Forget what you've heard about Tombstone, Deadwood, and Virginia City - Los Angeles was the toughest of the tough frontier towns. John Mack Faragher, Yale professor and author of Eternity Street, tallied 468 substantiated homicides between 1830 and 1874 (at a time when LA County's population grew from under 1,000 to about 6,000). And Los Angeles - with only a sheriff and some deputies - was ill-equipped to deal with its high levels of crime.

Michel Lachenais was a particularly nasty piece of work - murdering an unarmed man at a wake, beating one of his vineyard workers to death and covering it up, shooting a man in the face (the victim survived but was blinded), and, finally, murdering one of the owners of the farm next to his after an argument.

Previously, Lachenais had gotten away with his crimes. But he was clearly a dangerous man, and his antics were extremely embarrassing to the town's law-abiding French community. When he was finally arrested for the murder of Jacob Bell, vigilantes (many of them French-speaking) took notice.

Lachenais' arraignment was postponed for three days in the hopes that the vigilantes would calm down. It didn't work.

The vigilantes met at Stearns' Hall, named Felix Signoret the committee president, reviewed Lachenais' violent life, and decided that Lachenais should hang for his crimes.

On the day of the arraignment, Signoret led the Vigilance Committee to the jail. The mob overpowered Sheriff Burns and his deputies, dragged Lachenais to a nearby corral gate, and hanged him.

Many, many people have taken the law into their own hands when the justice system failed to secure any actual justice. Signoret wasn't the only respected civilian to participate in lynchings when the law failed to convict a known murderer.

Why did Signoret (and, for that matter, the rest of the mob) face no consequences? Judge Sepulveda, who was fed up with lynchings, asked the Grand Jury to investigate and indict the mob's leaders. The Grand Jury concluded that if the court had done its job the first time Lachenais committed murder, the lynching would never have taken place.

The death of Michel Lachenais was the very last lynching committed in California. The Chinese Massacre the following year qualifies as a race riot. (Incidentally, the Vigilance Committee - which still had Signoret as one of its leaders - issued a statement making it quite clear that they were NOT responsible for the brutal attack that left eighteen Chinese dead - and that they had, in fact, organized to stop the riot.)

Signoret and a business partner, Le Prince, had a bank exchange at Arcadia and Main (per the 1875 city directory).

Signoret passed away in 1878 after a long battle with edema and was survived by daughters Rosa, Anne, and Caroline (Catherine had passed away in 1877). The Signorets are buried together in Calvary Cemetery, along with their children Felix and Louise.

As for the Signorets' elegant home on Aliso Street, it was later repurposed...as a brothel.

Friday, September 4, 2020

To Los Angeles On Her 239th Birthday

Whether September 4, 1781 was your exact founding date has been the subject of some debate, but no one alive today was there to see it, so like most Angelenos I'm content to consider today your birthday.

I know. It's a weird birthday and you can't celebrate like usual. Hopefully next year will be better. And ten years after that, your 250th should really be a big deal.

I think of you often, Los Angeles. I may live in a suburb (for reasons beyond the scope of this entry), but you've certainly been on my mind today. And it's because you're not okay.

I care about you, Los Angeles. I am bothered by the fact that you're not being looked after as well as you should be (with the exception of your wealthiest areas, you've been dirty and suffering from some degree of deferred maintenance for my entire life) and I am bothered that we keep losing so much of what makes you great to apathy, corruption, and greed. I am especially not happy with the poor stewardship you've been subjected to for all of this century and too much of the last one. It's not right and you deserve better.

I worry about you, Los Angeles. I worry about Angelenos who are struggling to survive on the street, or who are facing that prospect. I worry about you when a fire breaks out, and if a big enough earthquake hits (I haven't forgotten the 1994 Northridge quake), I'll worry then too. I worry about you when civilians clash with law enforcement. I worry that a certain subsection of the population - the people who just want to watch the world burn - hasn't learned anything from the 1871 Chinese Massacre, the 1965 Watts Riots, or the 1992 riots, and won't learn anything from 2020.

I weep for you, Los Angeles. I weep for the shameful and cruel way homeless Angelenos are treated. I weep for your public schools that are mediocre at best and shouldn't be. I weep for our losses - LACMA, Bunker Hill, pre-concrete Pershing Square. I weep for every exhausted commuter who can't live close to work due to finances or safety issues and rarely sees their loved ones. I weep for every Angeleno who doesn't have the right look or the right brand and thinks they're not enough (and I know a thing or two about this - I'm a pale, dark-haired, curvy Valley Girl who plays with scale models).

I pray for you, Los Angeles. I pray for civility, understanding, and peace between Angelenos. I pray that we'll stop losing the best of you to corruption, bribery, massive egos, and political favors. I pray for developers to think more like Prudent Beaudry (who developed for the wealthy, the working class, and everyone in between) and less like the people who plan to replace the Viper Room with a 15-story tower. I pray that we can save more of what makes you unique and special. I pray that the neglected Pico House doesn't rot from the inside out. I pray you'll have good, honest, and competent leadership in the near future, since in your 239 years of history you've had a lot of bad mayors and a lot of bad council members, and the people currently in charge are grossly unfit to care for you.

I love you, Los Angeles. Which is why I'm scared for you.

On this day I'm reminded of a scene from "Penny Dreadful: City of Angels". Tiago asks Lewis how they're going to save Los Angeles. Lewis responds that they're just trying to survive her. But how will you survive, Los Angeles?

My grandparents loved you so much. My parents say you used to be a great place to live. No one wants to see you turn into New York (both in terms of ugly skyscrapers and in terms of crime rate and livability).

Happy birthday, Los Angeles. May you rise from the ashes of 2020, no matter how impossible it seems (even Hurricane Katrina couldn't kill New Orleans).

With love from one of your millions of kids,

C.C.

Sunday, October 10, 2021

Erasing Frenchtown in Maps

I have been mapping historic French LA for 8.5 years.

It's harder than it looks. Among the many, MANY changes to the street grid, the intersection of Alameda and Aliso was erased, with Aliso rerouted into Commercial at Alameda Street in the 1950s to accommodate the 101 Freeway.

I get a lot of questions about this, and I think it's easier to explain with maps.This 1894 map detail shows the Maier and Zobelein brewery, formerly the El Aliso winery, in the bottom left corner. By this point, Jean-Louis Vignes' vineyard (formerly ground zero for the French community in LA) had been thoroughly developed into a mostly-residential neighborhood, and was still full of French residents like the Ducommuns, the Lazards, and Joseph Mascarel (who died in his Lazard Street home just a few years after this map was made). Maier and Zobelein was rebranded as Brew 102 in the 1940s, with the brewery tanks easily visible from the freeway and in photos.

Zoom in and you can see that Ducommun Street (misspelled here as "Ducummen") and Lazard Street were once two separate streets. Today, it's all Ducommun and it no longer reaches all the way to Alameda Street.

When the original street grid has been altered to this extent, mapping French LA is a bigger challenge than everyone thinks it is. On top of that, LA added numbering fairly late. I do still plan to reveal the Great Big Map of French LA someday; I'm just not sure when (or if) I'll ever be "done" enough.