Last weekend, I gave a presentation on the French in Southern California at San Diego Mensa's Regional Gathering in Palm Springs (video coming soon - IF I can get the darn thing uploaded).

The first, and most revealing, question in the Q&A concerned why LA's historically French neighborhoods are now associated with other ethnic groups.

The original Frenchtown - bordered by Main Street, 1st Street, Aliso Street, and the LA River - is now largely split between Little Tokyo and the industrial core, with the Civic Center bleeding into the northern end of the neighborhood.

As Frenchtown expanded to the north, it grew to include modern-day Chinatown. Why is Joan of Arc standing outside Chinatown's only hospital? Because it was the French Hospital until 1989, and until the 1930s, it was a French neighborhood. Naud Junction, the Fritz houses, and Philippe the Original (creators of the French Dip sandwich; in that location since 1951) are all in Chinatown for the very simple reason that it wasn't always Chinatown. (LA's original Chinatown was demolished in 1931 to build Union Station - long after the Sainsevain brothers lost their uncle's vineyard).

Pellissier Square is now called Koreatown. Why? Because much of central LA declined after the 1930s, making it an affordable place for Korean immigrants to live and start businesses by the time the Korean War ended.

They weren't the first Koreans in Los Angeles. Historically, Korean Angelenos tended to live in Bunker Hill.

(Incidentally, "Koreatown" is something of a misnomer. HALF of Koreatown residents are Latino, and only about one-third are Asian. Korean Angelenos do, however, account for most of the area's businesses.)

There are still clues to Koreatown's French origins. Normandie Avenue, one of the longest streets in Los Angeles County (stretching 22.5 miles between Hollywood and Harbor City), runs smack down the middle of Koreatown. The Pellissier Building, including the legendary Wiltern Theatre, proudly towers over Wilshire and Western. And if you look at the neighborhood's architecture - sure, it's largely Art Deco, but some of it is also French-influenced.

In the early days, Los Angeles was a fairly tolerant place. It wasn't a utopia by any means (case in point: the Chinese Massacre of 1871), but Los Angeles was more tolerant of non-WASPs than most North American cities.

By the 1920s, a plague began to infest Los Angeles on a grand scale.

Deed restrictions.

Sometimes called restrictive covenants, deed restrictions barred ethnic and/or religious groups from buying homes in particular areas.

Why? Who would do something so hateful?

Let's start by rewinding the clock to the 1850s.

In 1850, California became a state. Legally, Los Angeles should have started opening public schools at this point (due to separation of church and state), but LAUSD wasn't founded until 1853. By this time, there was a growing number of Protestant families - most of them Yankees - in town. The few schools that did exist in the area were all Catholic, and Protestant parents objected - loudly - to the idea of sending their kids to Catholic schools. (Many Catholic schools do accept non-Catholic students, and many non-Catholic parents may prefer them if the local public schools aren't good enough. But things were a little different 164 years ago.)

Fast-forward to the 1880s.

When railroads first connected Southern California to the rest of the United States, newcomers flooded the area. Most were WASPs, and the majority were from the Midwest.

Guess where else deed restrictions were common? That's right - the WASPy Midwest. (No offense to any WASPs or Midwesterners who may read this, but I don't believe in hiding the truth. I sure as hell have never pretended French Californians were perfect.)

Before too long, deed restrictions barred people of color from much of the city. Some even excluded Jews, Russians, and Italians. Homeowners' associations and realtors often worked together to keep restricted neighborhoods homogeneous. (My skin is crawling as I write this.)

Excluded ethnic and religious groups, therefore, tended to live in areas that weren't restricted against them.

French Angelenos, however, were a pretty tolerant bunch.

The first baker in the city to make matzo was Louis Mesmer, who was Catholic. His daughter Tina married a Protestant.

Harris Newmark - German and Jewish - was one of Remi Nadeau's best friends.

Prudent Beaudry's sometime business partner Solomon Lazard - French and Jewish - was so popular among Angelenos of all ethnicities that Spanish speakers called him "Don Solomon".

French Basque Philippe Garnier built a commercial building specifically to lease it to Chinese merchants, who weren't considered human beings by the United States government at the time.

No one batted an eye at the fact that quite a few of LA's earlier Frenchmen (including Louis Bauchet, Joseph Mascarel, and Miguel Leonis) married Spanish, Mexican, or Native American women.

Frenchtown didn't have deed restrictions. (It's true that we don't always get along with everyone, but you won't find many French people willing to do something that asinine.)

The original core of Frenchtown was largely taken over by the civic center and industry when the area was redeveloped in the 1920s (and when the 101 sliced through downtown). But part of it became Little Tokyo. Why? No deed restrictions.

In fact, when Japanese American internment emptied Little Tokyo during World War II, African Americans (many working in the defense industry) poured into the neighborhood, and for a time it was known as "Bronzeville". Again, it was still one of the few areas with no deed restrictions. (On a personal note, the original paperwork for my childhood home in Sherman Oaks - built in 1948 - included a restriction against selling to African Americans. No other ethnicities were excluded. Which should give my dear readers a rough idea of what African American home buyers faced at the time - and renters had even fewer choices. Deed restrictions were legally struck down in California in 1947 and nationwide in 1948, but in Los Angeles, they persisted into the 1950s. Nationwide, it was probably worse.)

LA's original Chinatown was emptied and razed to build Union Station. Where did all the Chinese Angelenos go? The area now known as Chinatown was full of French Angelenos first. Wikipedia incorrectly states that it was originally Little Italy. It's true that Italians did live in the neighborhood, but the French arrived before the first Italians did, and made up a larger percentage of the population. Why did the demographics change? No deed restrictions to keep out Chinese residents - or, for that matter, Italian residents. (Catholics of all origins occasionally clashed with Chinese Angelenos over religious differences, but the French community welcomed newcomers from Italy. Case in point: two of the French Benevolent Society's founding members were Italian. And the French Hospital did accept Chinese patients at a time when most hospitals wouldn't.)

LA's Jewish community was largely based in Boyle Heights for many years. Guess who else lived in Boyle Heights back in the day? There were Anglos, sure, but there were also Basque farmers. In fact, Simon Gless' big Victorian house was used as office space for the Hebrew Shelter Home and Asylum for many years (the last time I checked, it was a boarding house for mariachi musicians). Once again - no deed restrictions. (Why does Los Angeles County have so many Jewish residents? Because Jews have, historically, been more welcome in Los Angeles than in many other places. Los Angeles was a tiny frontier town when the first Jewish residents arrived, and in the Old West - where people had to work together to stay alive - how you treated people mattered more than what house of worship you attended.)

I haven't found anything on whether Pellissier Square ever had deed restrictions or not, but there's a reason Korean Angelenos originally clustered in Bunker Hill. Prudent Beaudry - who developed for everyone - developed Bunker Hill. Like Angelino Heights, Bunker Hill was unrestricted.

How did Frenchtown cease to be called Frenchtown?

Simple. As the city expanded westward, and as many French Angelenos moved west or left the city entirely in search of land for grazing livestock/farming/growing grapes, people who weren't welcome in other areas moved to the historically French - and historically unrestricted - neighborhoods.

If you were in the same situation, wouldn't you?

Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Showing posts with label Angelino Heights. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Angelino Heights. Show all posts

Saturday, June 3, 2017

Deed Restrictions and the Renaming of Frenchtown

Thursday, January 12, 2017

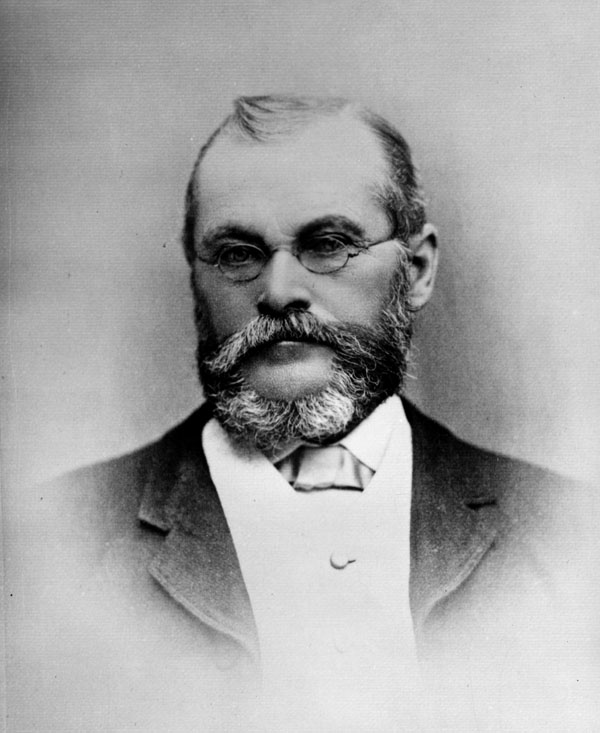

The Forgotten Beaudry Brother

We've covered Prudent Beaudry. But Victor, the youngest of the eight Beaudry siblings, is completely forgotten today.

Like his older brothers before him, Victor was born in Quebec in 1829 and educated in the best schools Montreal and New York had to offer. And like the rest of his brothers, he had a head for business and spoke fluent English. Since he arrived rather late in his parents' lives, Victor faced a challenge his brothers did not: he was only three years old when their father died.

In the late 1840s (sources disagree on whether it was before or after the Gold Rush began), Victor (now in his late teens) moved to San Francisco and established a successful shipping and commission business. Prudent, who was thirteen years older than Victor, later joined him, and the brothers then got into the ice business.

By 1850*, Victor was living in Los Angeles. He got back into the ice business with Damien Marchesseault, harvesting ice in the San Bernardino mountains and shipping it via mule train to Los Angeles. From the port of San Pedro, some of their ice was shipped to saloons in the faraway, but no less thirsty, city of San Francisco. Their ice house is long gone, but the area is still called Ice House Canyon. Victor also did some mining in the San Gabriel Valley and co-founded the Santa Anita Mining Company with Marchesseault in 1858. From 1855 to 1861, Victor managed Prudent's many business interests, at one point remodeling the aging Beaudry Block into Southern California's finest commercial building. He became a U.S. citizen in 1858 (beating older brother Prudent to citizenship by five years).

Three years later, Victor received a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and joined the First Regiment of Infantry in the United States Army, fighting for the Union cause. He remained in the Army until the bitter end of the Civil War, suffering health problems for much of his life as a result of his wartime experiences.

After the war, several of Victor's good friends from the Army were stationed at Camp Independence in Inyo County, and suggested he open a store there. This was a natural enough task for Victor, since he came from a family of successful merchants.

Victor soon acquired an interest in the Cerro Gordo silver mines, partnering with Mortimer Belshaw. Due to the mines' prodigious output (An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County puts the figure at 5,000,000 pounds of bullion per year), 400 mules were needed to haul the bullion 200 miles to San Pedro, where it would be sent via ship to San Francisco. Remi Nadeau (who had started his empire by borrowing $600 from Prudent to buy a freight wagon and mules) formed the Cerro Gordo Freighting Company with Victor and Belshaw. Years later, when Nadeau liquidated most of his freighting company's equipment, it was largely purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company - which just so happened to be partially owned by the Beaudry brothers. But we'll get into the details when we get to Remi Nadeau.

Because the Cerro Gordo mines stimulated so much business in the area (and on the route to LA), the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad was built. Before too long, the Southern Pacific Railroad also branched out to the Mojave Desert.

Victor returned to Montreal in 1872. The following year, he married the Sheriff of Montreal's daughter, Mary Angelena Le Blanc. Before long, the couple had five children (Victor, Oscar, Abel, Alva, and Mathilda). Victor returned to Los Angeles with his wife and children in 1881, building a house at 405 Temple Street (near Montreal Street, which was later renamed Hill Street) and working with Prudent in real estate development. You know this story. Angelino Heights, Temple Street Cable Railway, half of modern-day downtown...I won't rehash it here. Victor's name appeared in the real estate section of local newspapers almost as often as Prudent's (mostly regarding properties in the Angelino Heights and Beaudry Water Works tracts). The April 8, 1883 Los Angeles Daily Herald even lists Victor as the seller of Beaudry Park to the Los Angeles Infirmary (aka St. Vincent's Hospital).

Over the years, city directories and voter rolls simply listed Victor's occupation as "capitalist".

The Beaudrys returned to Montreal in 1886. Victor had experienced health issues since his stint in the Army, and by this time was suffering from inflammatory rheumatism. He passed away in Montreal on March 7, 1888. Prudent was notified by telegram that evening, and Victor's obituary appeared in the following morning's Los Angeles Herald.

For a few years after his death, Prudent and F.W. Wood, executors of Victor's estate, slowly liquidated Victor's impressive real estate holdings. (In November 1888, they were sued over an alleged one-fourth interest in the Old Cemetery tract Victor held. One of the plaintiffs was George S. Patton Sr. - General Patton's father.) Prudent is well known to local historians as a prodigious developer and real estate agent, but Victor's real estate interests were nothing to sneeze at.

The house on Temple Street is long gone. Today, the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels takes up most of the block. The former site of Victor's house is very close to the Cathedral's gift shop.

When Victor is remembered at all, he is remembered as Prudent's brother. While partnering with Prudent made him even wealthier, Victor accomplished quite a lot on his own and with different business partners. He should be remembered for his own merits, not merely for being the baby brother of two mayors.

*One source says Victor spent a few years in Nicaragua for business purposes. It does sound like something a Beaudry would do - however, I can't find a proper source citation, and the older sources say 1850. In the absence of proof, I'll leave 1850 as the date.

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

He Built This City: Mayor Prudent Beaudry

Possessing boundless energy, exceptional business sagacity and foresight, Prudent Beaudry amassed five fortunes and lost four in his ventures, which were gigantic for that time, and would be considered immense today.

Have a seat, everyone...the lifetime I'm chronicling this week is best described as "epic".

Jean-Prudent Beaudry was born July 24, 1816 in Mascouche, Quebec - close to Montreal. When he was a young boy, the family moved to the neighboring town of Saint-Anne-des-Plaines.

There were five Beaudry brothers (and three Beaudry sisters). All of the Beaudry brothers worked hard and got rich, but Prudent, Jean-Louis, and Victor would make the history books. (Victor, the only other Beaudry to settle in Los Angeles, will be covered in another entry, because this one is going to be LONG.)

The Beaudrys, an industrious family of traders, sent their sons to good schools in Montreal and New York. Prudent and his brothers had the benefits of a great education and English fluency when they went into business for themselves.

Which they did, many times over.

Prudent started out in his father's mercantile business, then went to work at a different mercantile house in New Orleans, returning to Canada in 1842 to partner with one of his brothers. By 1844, he left the business to join Victor, the youngest Beaudry brother, in San Francisco. The Gold Rush was a few years away, but Victor had already established a profitable shipping and commission business in the city. Before long, the brothers were in the ice business (Victor later partnered with another future mayor, Damien Marchesseault, in distributing ice harvested in the San Bernardino Mountains). Perhaps not surprisingly for a native of Quebec, Prudent also got into the syrup business. Two years later, after Prudent had lost most of his money on real estate speculation (and more of it when insufficiently insured stock was destroyed in a fire), Los Angeles beckoned.

I'll let Le Guide Francais take it from here:

Starting with $1,100 in goods and $200 cash in a small store on Main Street, where the City Hall now stands, it is said that he cleared $2,000 in thirty days, which enabled him to take a larger store on Commercial Street. From that time on, Prudent Beaudry was one of the preeminent men of the economic, social, and political life of the Southwest.(The book, just to clarify, refers to the current City Hall, not the old Bell Block down the street. After Beaudry vacated the Commercial Street shop, Harris Newmark moved in. Ironically, Beaudry sold his dry goods business to Newmark twelve years later.)

Having earned a well-deserved vacation, Prudent left Los Angeles for Paris in 1855. The chief items on his itinerary were seeing the Exposition Universelle and consulting the great French oculist Dr. Jules Sichel. Prudent visited Montreal on his return trip to visit his brother Jean-Louis, who would serve as Mayor of Montreal for a total of ten years between 1862 and 1885. The Beaudrys, needless to say, were just as prominent in business, politics, and society in Quebec as they were in Southern California.

While Prudent was away, Victor was capably managing his brother's business interests. Prudent had purchased a building on the northeast corner of Aliso and Los Angeles Streets in 1854 for $11,000. Victor spent $25,000 - an absolute fortune at the time - on remodeling and improving the building. In this case, it was money well spent. After the Beaudry Block was improved, it was considered the finest building in Southern California for the time. Rents increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Prudent returned to Los Angeles in 1861 (Victor had been offered a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and found it difficult to manage his brother's business interests at the same time). He continued in the mercantile business until 1865. Due to stress, he retired...but not for long. The Beaudrys just weren't capable of being unproductive.

In 1867, Prudent Beaudry made one of his greatest real estate investments. The steep hill above New High Street, which he purchased at a Sheriff's Department auction for the pittance of $55 (I can't believe it either), was known as Bunker Hill. It would soon become famous for its Victorian mansions.

This purchase set Beaudry on a path that made him California's first realtor and first large-scale developer, in addition to an urban planner. Before long, he was buying extensive tracts of land, dividing them into lots, and selling them, working out of an office opposite the Pico House. One 20-acre tract, between Charity (Grand) and Hill from Second to Fourth, cost $517 and netted $30,000. Another tract, consisting of 39 acres bordered by Fourth, Sixth, Pearl (Figueroa) and Charity (Grand), earned $50,000.

The Beaudry brothers (smartly) kept buying land. They predicted - correctly, and beyond their wildest dreams - that after railroad lines connected Los Angeles to San Francisco and the East Coast, new settlers would pour into Southern California in droves. (If they could only see how right they were!) Prudent also bought land in modern-day Arcadia and near the Sierra Nevada mountains (building aqueducts to redirect mountain streams to his properties), and helped to found the cities of Pasadena and Alhambra.

One newspaper advertisement from 1873 lists 83 (yes, 83!) separate lots for houses, in addition to two full city blocks, multiple city tracts, and large land parcels in Rancho San Pedro, Verdugo Ranch, and the Warner and de la Hortilla land grants. A similar ad from 1874 notes, in bold, which of the streets with lots for sale had already had water pipes installed. It's no wonder Beaudry was able to keep his real estate business going every time he lost most (or all) of his money.

Severe flooding in January 1868 had undone nearly all of Jean-Louis Sainsevain and Damien Marchesseault's hard work on the city's primitive water system. As a developer, Beaudry was very concerned about improving the city for its residents. On July 22, 1868, a 30-year contract for the water system was granted to the newly-established Los Angeles City Water Company. The three partners in the Company were Dr. John Griffin, French-born businessman Solomon Lazard, and, of course, Prudent Beaudry (most of the employees were also of French extraction - chief amongst them, Charles Lepaon, Charles Ducommun, and Eugene Meyer - more on them in the future).

The Los Angeles City Water Company replaced Sainsevain and Marchesseault's leaky wood pipes with 12 miles of iron pipes, and continued to regularly make improvements on the water system until the contract expired 30 years later (the city purchased the system for $2 million - in 1898 dollars!). Although nothing could cancel out the previous water problems or Marchesseault's tragic suicide, the city of Los Angeles finally had a reliable water system that wouldn't turn streets into sinkholes. (If you live in Los Angeles and you like having running water, thank a Frenchman. Seriously, you guys owe us.)

You're probably wondering how Prudent managed to supply water to his hilltop property. In those days, hills weren't desirable places to build homes because water had to be transported in barrels via trolley or other vehicle. The city water company wasn't interested in solving the problem. But in case you haven't noticed yet, Prudent was smart, resourceful, and didn't give up easily. He knew that if running water was available, prospective homeowners would be more likely to consider hilltop lots and pay a good price for them. So he constructed a huge reservoir and a pump system that supplied water from LA's marshy lowlands to Bunker Hill. The pump system worked perfectly - and so did his plan. (I'll bet every land speculator in Southern California wished they had thought of that.)

Before long, Bunker Hill became THE place to build grand homes. At least two of its fabled Victorian mansions were built for other French Angelenos - entrepreneur Pierre Larronde and model citizen Judge Julius Brousseau.

Let it be known, however, that Beaudry developed for everyone. It's true that he built mansions and had a keen interest in architecture, but he also built modest homes on small lots for working families. And because he made modest properties available for small monthly payments, he made home ownership possible for buyers with lower incomes. He made considerable improvements to his land - paving roads, planting trees, and providing for water usage.

And Beaudry just kept developing land for the rest of his life. This Lost LA article includes an 1868 map showing five tracts recently developed by Beaudry.

The Bellevue tract included a garden he dubbed "Bellevue Terrace". This early park rose 70 feet above downtown, boasting hundreds of eucalyptus and citrus trees. Beaudry eventually put the site up for sale. The State of California bought it to develop a Los Angeles campus of the State Normal School, which would later become UCLA. When UCLA moved to Westwood in the 1920s, the hill was graded down and replaced with Central Library.

A few miles away, where North Beaudry Avenue meets Sunset Boulevard, there is an oval-shaped parcel of land that currently holds a church, a restaurant, and The Elysian apartment building. In the early 1870s, this was Beaudry Park - another garden paradise on a hill, boasting citrus groves and eucalyptus trees (and vineyards!). But the Beaudrys put it on the market a decade later. The Sisters of Charity snapped it up in 1883, building a newer facility and relocating St. Vincent's Hospital (sometimes called the Los Angeles Infirmary) here.

Beaudry owned a large tract containing one block of stagnant, foul-smelling marshland. No one wanted to build on the land, and it wasn't ideally suited to building anyway. In 1870, Beaudry got the idea to drain the marsh and turn the land into a public park. Naturally, he spearheaded the plan. Originally called Los Angeles Park, the land was renamed Central Park in the 1890s...and was renamed again later.

You know this park. There's a good chance you've been there (and there's a VERY good chance you absolutely hate its current incarnation).

Give up yet?

It's Pershing Square. (It used to be a very nice park. Trust me on this.)

Beaudry's dedication to developing, planning, and improving the city got him started in politics. He was elected to the Los Angeles Common (City) Council for three one-year terms (1871, 1872, and 1873). In 1873, he became the first president of the city's new Board of Trade. His name appeared in Los Angeles newspapers frequently throughout the 1870s and 1880s - mostly in the real estate sections (and in a bankruptcy case...the Temple and Workman Bank failed and took most of his money with it).

In 1874, Prudent Beaudry became Los Angeles' third French mayor, serving two terms. At the same time, his brother Jean-Louis Beaudry was serving as mayor of Montreal.

After finishing his second term, Beaudry bought the local French-language newspaper, L'Union. (I will cover LA-based French newspapers - three or four are known to have existed - at a later date.) Beaudry was already a director of the Los Angeles City and County Printing and Publishing Company.

Nearly all of Los Angeles' Victorian houses have been torn down over the years. However, neighborhoods like Angelino Heights still have Victorian-era homes. Guess who developed Angelino Heights? That's right - Prudent and Victor Beaudry (architect Joseph Newsom designed many of the houses). Carroll Avenue, beloved by preservationists for its high concentration of surviving Victorian homes (kitsch king Charles Phoenix even includes it on his annual Disneyland-themed DTLA tour as "Main Street USA"), is well within the original boundaries of Angelino Heights.

In the 1880s, Angelino Heights was one of LA's earliest suburbs. Cars would not be commonly used for quite some time. To serve the transit needs of potential home buyers, the Beaudry brothers (with several other real estate promoters) built the Temple Street Cable Railroad. This streetcar ran along Temple Street from Edgeware to Spring (it was soon extended to Hoover Street) every ten minutes and ran for 16 hours each day, making transportation fast and simple for residents of Angelino Heights and Bunker Hill. The Pacific Electric Railway eventually purchased the line (switching from cable cars to electric trolleys in 1902), and in time it passed to the Los Angeles Railway. The Temple Street Cable Railroad - far and away the most successful streetcar line in the city's history - ran from 1886 to 1946. SIXTY YEARS. Which is especially impressive considering the Pacific Electric Railway didn't even exist until 1901, and its less-traveled streetcar lines were converted to bus routes in 1925.

Funnily enough, Beaudry had sued the Los Angeles Railway in 1891. He claimed the Railway had excavated First and Figueroa Streets without the proper authority, rendered the streets useless, and blocked access to his property. (He also occasionally sued people who damaged his properties. Can you blame the guy? Building a city is hard work.)

When "Crazy Remi" Nadeau decided to liquidate most of his freighting company's equipment, it was purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company...which counted Prudent and Victor Beaudry among its shareholders. In the 1880s, the Beaudrys began to take on fewer and fewer projects, but they both remained vocal supporters of developing and improving Los Angeles.

Prudent Beaudry passed away on May 29, 1893, a week after suffering a paralytic stroke (Victor had passed away in 1888, with Prudent acting as executor of his sizable estate). An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County stated:

Prudent Beaudry, in particular, has the record of having made in different lines five large fortunes, four of which, through the act of God, or by the duplicity of man, in whom he had trusted, have been lost; but even then he was not discouraged, but faced the world, even at an advanced age, like a lion at bay, and his reward he now enjoys in the shape of a large and assured fortune. Of such stuff are the men who fill great places, and who develop and make a country. To such men we of this later day owe much of the beauty and comfort that surround us, and to such we should look with admiration as models upon which to form rules of action in trying times.Beaudry died a wealthy man (despite losing his fortune FOUR times), but ironically, he might have died even wealthier. A 1905 article in the Los Angeles Herald stated that nearly forty years previously (i.e. in the 1860s), he had begun to dig a well on one of his hilltop properties. After several hundred feet, he struck a deposit that "looked and smelled like tar." He promptly abandoned the half-dug well. That's right - Beaudry struck oil. But he wasn't looking for oil and had no use for it. Had he made the same discovery a few decades later, things may have been a little different.

The late Mayor's body was returned to his native Quebec. Like the rest of his family, he is buried at Notre Dame des Neiges (Canada's largest, and arguably most beautiful, cemetery). He never married and had no children, so his estate went to the other Beaudry siblings and their families.

Prudent Beaudry's importance as an urban planner and city developer is almost completely forgotten today. His work lingers in the names of Beaudry Avenue, Bellevue Avenue, and various other French-named streets in tracts he developed long ago. (Hill Street was once called Montreal Street in honor of the brothers' hometown - it isn't clear when it was renamed.)

(And, thankfully, Angelino Heights is still standing. I will lose my last remaining shreds of faith in humanity if something bad happens to those precious few surviving Victorians.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)