Possessing boundless energy, exceptional

business sagacity and foresight, Prudent Beaudry amassed five fortunes

and lost four in his ventures, which were gigantic for that time, and

would be considered immense today.

-

Le Guide Francais, 1932

Have a seat, everyone...the lifetime I'm chronicling this week is best described as "epic".

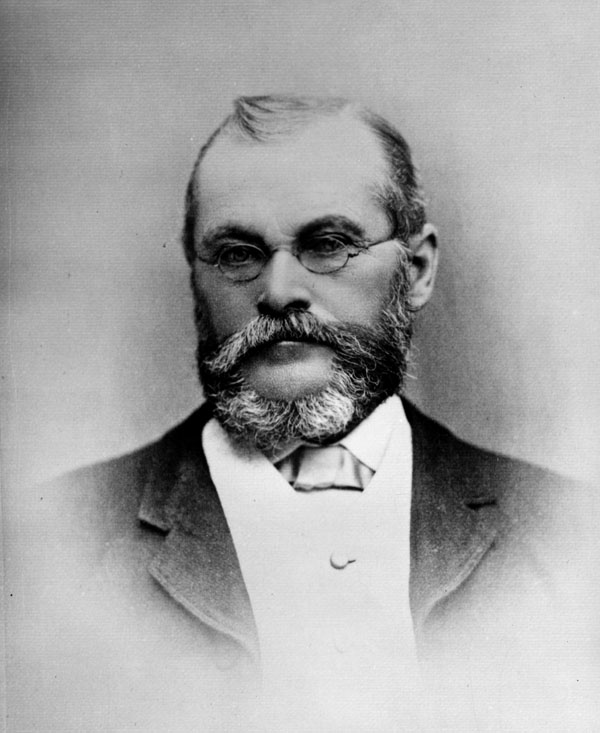

Jean-Prudent

Beaudry was born July 24, 1816 in Mascouche, Quebec - close to

Montreal. When he was a young boy, the family moved to the neighboring town of

Saint-Anne-des-Plaines.

There were five Beaudry

brothers (and three Beaudry sisters). All of the Beaudry brothers worked hard and got rich, but Prudent, Jean-Louis, and Victor would make the history

books. (Victor, the only other Beaudry to settle in Los Angeles, will be

covered in another entry, because this one is going to be LONG.)

The

Beaudrys, an industrious family of traders, sent their

sons to good schools in Montreal and New York. Prudent and his brothers

had the benefits of a great education and English fluency when they went

into business for themselves.

Which they did, many times over.

Prudent

started out in his father's mercantile business, then went to work at a

different mercantile house in New Orleans, returning to Canada in 1842

to partner with one of his brothers. By 1844, he left the business to

join Victor, the youngest Beaudry brother, in San Francisco. The Gold

Rush was a few years away, but Victor had already established a

profitable shipping and commission business in the city. Before long,

the brothers were in the ice business (Victor later

partnered with another future mayor,

Damien Marchesseault, in distributing ice harvested in the San Bernardino Mountains). Perhaps not surprisingly for a native of Quebec, Prudent also

got into the syrup business. Two years later, after Prudent had lost

most of his money on real estate speculation (and more of it when

insufficiently insured stock was destroyed in a fire), Los Angeles

beckoned.

I'll let

Le Guide Francais take it from here:

Starting

with $1,100 in goods and $200 cash in a small store on Main Street,

where the City Hall now stands, it is said that he cleared $2,000 in

thirty days, which enabled him to take a larger store on Commercial

Street. From that time on, Prudent Beaudry was one of the preeminent men

of the economic, social, and political life of the Southwest.

(The book, just to clarify, refers to the

current City Hall, not the old Bell Block down the street. After Beaudry vacated the Commercial Street shop, Harris Newmark moved in. Ironically, Beaudry sold his dry goods business to Newmark twelve years later.)

Having

earned a well-deserved vacation, Prudent left Los Angeles for Paris in

1855. The chief items on his itinerary were seeing the

Exposition Universelle and consulting the great French oculist

Dr. Jules Sichel.

Prudent visited Montreal on his return trip to visit his brother

Jean-Louis, who would serve as Mayor of Montreal for a total of ten

years between 1862 and 1885. The Beaudrys, needless to say, were just as

prominent in business, politics, and society in Quebec as they were in

Southern California.

While Prudent was away, Victor was

capably managing his brother's business interests. Prudent had

purchased a building on the northeast corner of Aliso and Los Angeles

Streets in 1854 for $11,000. Victor spent $25,000 - an absolute fortune

at the time - on remodeling and improving the building. In this case, it

was money well spent. After the Beaudry Block was improved, it was

considered the finest building in Southern California for the time.

Rents increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Prudent

returned to Los Angeles in 1861 (Victor had been offered a contract to

supply the Army of the Potomac and found it difficult to manage his

brother's business interests at the same time). He continued in the

mercantile business until 1865. Due to stress, he retired...but not for long. The Beaudrys just weren't capable of being unproductive.

In 1867,

Prudent Beaudry made one of his greatest real estate investments. The

steep hill above New High Street, which he purchased at a Sheriff's

Department auction for the pittance of $55 (I can't believe it either),

was known as

Bunker Hill. It would soon become famous for its Victorian mansions.

This

purchase set Beaudry on a path that made him California's first realtor

and first large-scale developer, in addition to an urban planner.

Before long, he was buying extensive tracts of land, dividing them into

lots, and selling them, working out of an office opposite the Pico

House. One 20-acre tract, between Charity (Grand) and Hill from Second

to Fourth, cost $517 and netted $30,000. Another tract, consisting of 39

acres bordered by Fourth, Sixth, Pearl (Figueroa) and Charity (Grand),

earned $50,000.

The Beaudry brothers (smartly) kept

buying land. They predicted - correctly, and beyond their wildest dreams

- that after railroad lines connected Los Angeles to San Francisco and

the East Coast, new settlers would pour into Southern California in

droves. (If they could only see how right they were!) Prudent also

bought land in modern-day Arcadia and near the Sierra Nevada mountains

(building aqueducts to redirect mountain streams to his properties), and

helped to found the cities of Pasadena and Alhambra.

One

newspaper advertisement from 1873 lists 83 (yes, 83!) separate lots for

houses, in addition to two full city blocks, multiple city tracts, and

large land parcels in Rancho San Pedro, Verdugo Ranch, and the Warner

and de la Hortilla land grants. A similar ad from 1874 notes, in bold,

which of the streets with lots for sale had already had water pipes

installed. It's no wonder Beaudry was able to keep his real estate

business going every time he lost most (or all) of his money.

Severe flooding in January 1868 had undone nearly all of

Jean-Louis Sainsevain and

Damien Marchesseault's

hard work on the city's primitive water system. As a developer, Beaudry

was very concerned about improving the city for its residents. On July

22, 1868, a 30-year contract for the water system was granted to the

newly-established Los Angeles City Water Company. The three partners in

the Company were Dr. John Griffin, French-born businessman Solomon

Lazard, and, of course, Prudent Beaudry (most of the employees were also

of French extraction - chief amongst them, Charles Lepaon, Charles

Ducommun, and Eugene Meyer - more on them in the future).

The

Los Angeles City Water Company replaced Sainsevain and Marchesseault's

leaky wood pipes with 12 miles of iron pipes, and continued to regularly

make improvements on the water system until the contract expired 30

years later (the city purchased the system for $2 million - in 1898

dollars!). Although nothing could cancel out the previous water problems

or Marchesseault's tragic suicide, the city of Los Angeles finally had a

reliable water system that wouldn't turn streets into sinkholes. (If

you live in Los Angeles and you like having running water, thank a

Frenchman. Seriously, you guys owe us.)

You're probably wondering how Prudent

managed to supply water to his hilltop property. In those days, hills

weren't desirable places to build homes because water had to be

transported in barrels via trolley or other vehicle. The city water

company wasn't interested in solving the problem. But in case you

haven't noticed yet, Prudent was smart, resourceful, and didn't give up

easily. He knew that if running water was available, prospective

homeowners would be more

likely to consider hilltop lots and pay a good price for them. So he

constructed a huge reservoir and a pump system that supplied water from

LA's marshy lowlands to Bunker Hill. The pump system worked perfectly - and so did his plan. (I'll bet every land speculator in Southern California wished they had thought of that.)

Before

long, Bunker Hill became THE place to build grand homes. At least two

of its fabled Victorian mansions were built for other French Angelenos -

entrepreneur

Pierre Larronde and model citizen

Judge Julius Brousseau.

Let

it be known, however, that Beaudry developed for everyone. It's true

that he built mansions and had a keen interest in architecture, but he

also built modest homes on small lots for working families. And because he made modest properties available for small monthly payments, he made home ownership possible for buyers with lower incomes. He made considerable

improvements to his land - paving roads, planting trees, and providing

for water usage.

And Beaudry just kept developing land for the rest of his life.

This Lost LA article includes an 1868 map showing five tracts recently developed by Beaudry.

The Bellevue tract included a garden he dubbed "Bellevue Terrace". This

early park rose 70 feet above downtown, boasting hundreds of eucalyptus

and citrus trees. Beaudry eventually put the site up for sale. The State

of California bought it to develop a Los Angeles campus of the State

Normal School, which would later become UCLA. When UCLA moved to

Westwood in the 1920s, the hill was graded down and replaced with

Central Library.

A few miles away, where North Beaudry

Avenue meets Sunset Boulevard, there is an oval-shaped parcel of land

that currently holds a church, a restaurant, and The Elysian apartment

building. In the early 1870s, this was Beaudry Park - another garden

paradise on a hill, boasting citrus groves and eucalyptus trees (and

vineyards!). But the Beaudrys put it on the market a decade later. The

Sisters of Charity snapped it up in 1883, building a newer facility and

relocating St. Vincent's Hospital (sometimes called the Los Angeles

Infirmary) here.

Beaudry owned a large tract containing one block of

stagnant, foul-smelling marshland. No one wanted to build on the land,

and it wasn't ideally suited to

building anyway. In 1870, Beaudry got the idea to drain the marsh and turn the land

into a public park. Naturally, he spearheaded the plan.

Originally called Los Angeles Park, the land was renamed Central Park in the

1890s...and was renamed again later.

You know this

park. There's a good chance you've been there (and there's a VERY good

chance you absolutely hate its current incarnation).

Give up yet?

It's

Pershing Square. (It used to be a very nice park. Trust me on this.)

Beaudry's

dedication to developing, planning, and improving the city got him

started in politics. He was elected to the Los Angeles Common (City)

Council for three one-year terms (1871, 1872, and 1873). In 1873, he

became the first president of the city's new Board of Trade. His name

appeared in Los Angeles newspapers frequently throughout the 1870s and

1880s - mostly in the real estate sections (and in a bankruptcy

case...the Temple and Workman Bank failed and took most of his money

with it).

In 1874, Prudent Beaudry became Los Angeles' third French mayor, serving two terms. At the same time, his brother

Jean-Louis Beaudry was serving as mayor of Montreal.

After finishing his second term, Beaudry bought the local French-language newspaper,

L'Union. (I

will cover LA-based French newspapers - three or four are known to have

existed - at a later date.) Beaudry was already a director of the Los

Angeles City and County Printing and Publishing Company.

Nearly

all of Los Angeles' Victorian houses have been torn down over the

years. However, neighborhoods like Angelino Heights still have

Victorian-era homes. Guess who developed Angelino Heights? That's right -

Prudent and Victor Beaudry (architect Joseph Newsom designed many of the houses). Carroll Avenue, beloved by preservationists

for its high concentration of surviving Victorian homes (kitsch king

Charles Phoenix even includes it on his annual

Disneyland-themed DTLA tour as "Main Street USA"), is well within the original boundaries of Angelino Heights.

In

the 1880s, Angelino Heights was one of LA's earliest suburbs. Cars

would not be commonly used for quite some time. To serve the transit

needs of potential home buyers, the Beaudry brothers (with several other

real estate promoters) built the

Temple Street Cable Railroad.

This streetcar ran along Temple Street from Edgeware to Spring (it was

soon extended to Hoover Street) every ten minutes and ran for 16 hours

each day, making transportation fast and simple for residents of

Angelino Heights and Bunker Hill. The Pacific Electric Railway

eventually purchased the line (switching from cable cars to electric

trolleys in 1902), and in time it passed to the Los Angeles Railway. The

Temple Street Cable Railroad - far and away the most successful

streetcar line in the city's history - ran from 1886 to 1946. SIXTY

YEARS. Which is especially impressive considering the Pacific Electric

Railway didn't even exist until 1901, and its less-traveled streetcar

lines were converted to bus routes in 1925.

Funnily

enough, Beaudry had sued the Los Angeles Railway in 1891. He claimed the

Railway had excavated First and Figueroa Streets without the proper

authority, rendered the streets useless, and blocked access to his

property. (He also occasionally sued people who damaged his properties.

Can you blame the guy? Building a city is hard work.)

When

"Crazy Remi" Nadeau decided to liquidate most of his freighting

company's equipment, it was purchased by the Oro Grande Mining

Company...which counted Prudent and Victor Beaudry among its

shareholders. In the 1880s, the Beaudrys began to

take on fewer and fewer projects, but they both remained vocal

supporters of developing and improving Los Angeles.

Prudent

Beaudry passed away on May 29, 1893, a week after suffering a paralytic

stroke (Victor had passed away in 1888, with Prudent acting as executor

of his sizable estate).

An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County stated:

Prudent

Beaudry, in particular, has the record of having made in different

lines five large fortunes, four of which, through the act of God, or by

the duplicity of man, in whom he had trusted, have been lost; but even

then he was not discouraged, but faced the world, even at an advanced

age, like a lion at bay, and his reward he now enjoys in the shape of a

large and assured fortune. Of such stuff are the men who fill great

places, and who develop and make a country. To such men we of this later

day owe much of the beauty and comfort that surround us, and to such we

should look with admiration as models upon which to form rules of

action in trying times.

Beaudry died a wealthy

man (despite losing his fortune FOUR times), but ironically, he might

have died even wealthier. A 1905 article in the

Los Angeles Herald

stated that nearly forty years previously (i.e. in the 1860s), he had

begun to dig a well on one of his hilltop properties. After several

hundred feet, he struck a deposit that "looked and smelled like tar." He

promptly abandoned the half-dug well. That's right -

Beaudry struck oil.

But he wasn't looking for oil and had no use for it. Had he made the

same discovery a few decades later, things may have been a little

different.

The late Mayor's body was returned to his native Quebec. Like the rest of his family, he is buried at

Notre Dame des Neiges

(Canada's largest, and arguably most beautiful, cemetery). He never

married and had no children, so his estate went to the other Beaudry

siblings and their families.

Prudent Beaudry's

importance as an urban planner and city developer is almost completely

forgotten today. His work lingers in the names of Beaudry Avenue,

Bellevue Avenue, and various other French-named streets in tracts he

developed long ago. (Hill Street was once called Montreal Street in honor of the brothers' hometown - it isn't clear when it was renamed.)

(And, thankfully, Angelino Heights

is still standing. I will lose my last remaining shreds of faith in humanity if

something bad happens to those precious few surviving Victorians.)