When you hear "Hollywood" and "makeup" in the same sentence, who do you think of? Max Factor, whose building now houses the Hollywood Museum? The Westmores, who have a star on the Walk of Fame? Or perhaps one of the celebrity makeup artists working today?

What would you say if I told you a French-speaking Belgian had his own shop on Hollywood Boulevard?

|

| Joseph G. Godissart in 1934 |

Joseph G. Godissart was born in Roux, Belgium, about twenty miles from the French border, in 1877. The Godissarts came to Los Angeles in 1910, moving into a bungalow at 808 South Harvard Boulevard in what is now Koreatown.

Godissart's daughter Sylvia was a quadruple threat - she acted, sang, danced, and played the piano. She was already appearing in Universal films and local stage productions as a teenager, and in 1919, she went to France for two years to study stage acting after completing a course at the Egan School of Drama.

|

| 1919 clip on Sylvia Godissart going to France to study acting |

Godissart accompanied his 16-year-old daughter to Paris and studied the art and science of perfume under A. Muraour, one of France's most renowned chemists, an author of technical books on perfume, and founder of the perfume company Nissery.

At least one newspaper account suggested that Alice Godissart would be joining her husband and daughter in Paris, but there was trouble in paradise. Godissart filed for divorce in Reno in 1920, claiming Alice had been extremely cruel to him and alleging that she had cheated with a doctor. Alice disputed this, stating that he had failed to adequately support her. She stated that while he was in France during the war, he left only $1000 for her to live on, forcing her to rent out the family home.

Alice Godissart stated that when her husband left in January of 1920, he left only $10,000 of the couple's community property, estimated at $100,000. She filed her own divorce complaint in Los Angeles in 1924, denying the allegations of infidelity and asserting that the claims had caused her humiliation and mental anguish. Additionally, she suspected that Godissart had hidden the bulk of their money in French banks.

Godissart moved to Paris and obtained a divorce decree there. Alice fought this decree, and in 1926 Judge Hollzer of Los Angeles Superior Court ruled that "Defendant was not in good faith a resident of Paris at the time, and therefore not subject to the jurisdiction of that tribunal. It is apparent he simply went to Paris for the purpose of getting a divorce. Such a trip does not establish residence. Decree for the plaintiff." Alice got the house.

Regardless of the Godissarts' allegations against each other, just a few months later they jointly threw Sylvia's engagement party at the Encino Country Club, and Godissart began building his cosmetics business.

I should note that there is conflicting information about precisely when Godissart's perfume business launched. Some sources claim that Godissart was a former restauranteur, others that he was a retired wealthy merchant, and Godissart himself claimed that his family had been making perfume for six generations, or since 1732. Another article (see below) claims that the Godissarts had been making perfume for 300 years. This seems to conflict with the fact that Godissart was from a part of Belgium that is not close to the perfume industry's epicenter in Southern France, and that I can't find any record of him being in the perfume business until the 1920s. In fact, I can't find any mention of the Godissart family in the perfume industry prior to that. References to the Godissarts prior to the opening of the first Godissart store do not mention perfume at all. (If anyone finds proof of the company's existence prior to 1925, please contact me with citations.)

There are multiple references to Godissart managing the Richelieu Cafe company, which lends weight to a background in the restaurant industry. He is cited as a former proprietor of Cafe de Paris in a 1912 ad for the Richelieu Cafe. Interestingly, when Levy's Cafe lost its liquor license under Godissart's co-management, it reopened as Richelieu Cafe, got a new license, lost it again, and closed in 1913.

Godissart also claimed to be a descendant of the man who inspired Balzac's Felix Gaudissart stories. However, available records on the Godissart family seem to run out with Godissart's father.

Godissart rigorously tested his ideas in France - arguably the toughest perfume market of all - before returning to Los Angeles. He set up a modern laboratory in Hollywood, where perfume was made from raw materials he imported from the main laboratory in Asnières.

Godissart also made face powder. Le Guide Français claims "The unique idea of mixing face powder in the presence of the customers to suit their complexion or taste originated with this farsighted parfumeur."

Godissart then began opening his own stores. Godissart's Parfum Classique Français first opened at 744 West 7th Street in 1925, and was so popular that within a year a second store opened at 313 South Broadway (inside the Million Dollar Theatre).

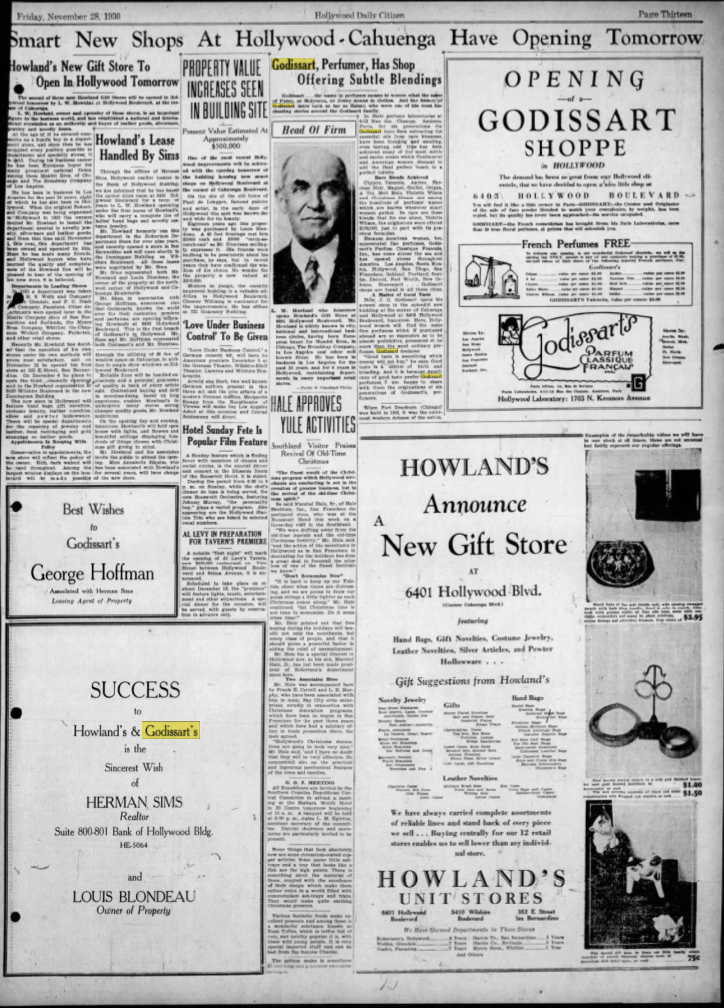

Finally, a store opened at 6403 Hollywood Boulevard in 1930. From the main laboratory at 1703 North Kenmore, Godissart supplied stores in Los Angeles, Santa Monica, San Francisco, Oakland, Portland, Seattle, Detroit, Dallas, Fort Worth, Shreveport, and New Orleans. There was a satellite office at 14 Rue de Sevigne in Paris.

|

| 1930 newspaper page with multiple mentions of the new Godissart's store on Hollywood Boulevard. |

In an interesting side note, the above newspaper page names Louis Blondeau as the owner of the property. The Blondeau family's shuttered tavern housed Nestor Film Company, which had merged with Sylvia's former employer - Universal - in 1912. (If you're wondering about Sylvia, she married Ervin Adamson soon after returning from France and seems to have retired from acting at that point.)

|

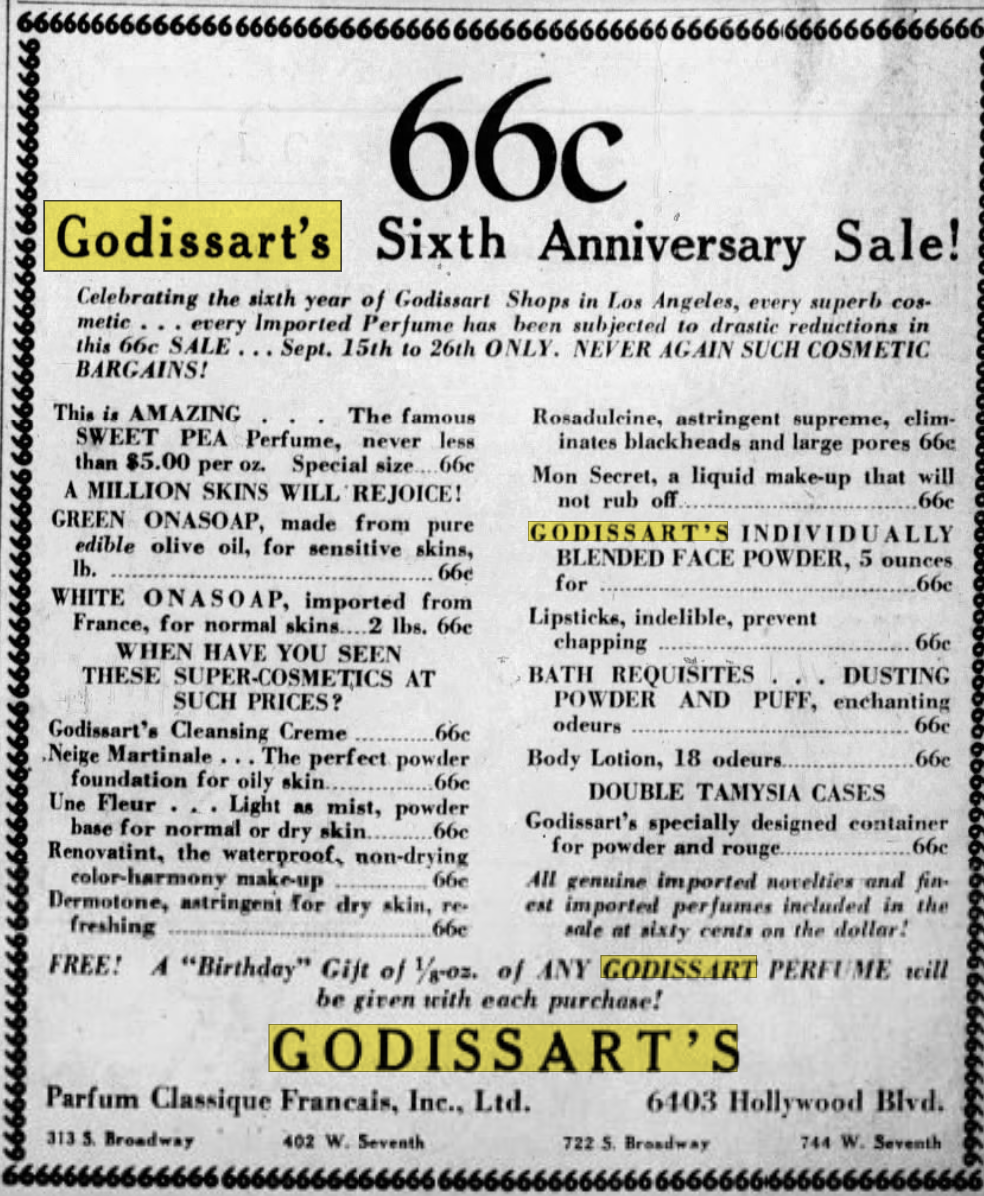

| 1931 ad for Godissart's sixth anniversary sale |

The 1931 ad above indicates that Godissart's had opened an additional 7th Street location, at number 744. The BLOC stands there today. Besides perfume and powder, Godissart's was selling lipsticks, soaps, skincare products, and dusting powder (applied to the body after bathing).

Another Broadway location opened in 1933, at number 709. Pictures of Godissart stores are elusive, but an article on the store's opening provides an idea of how they looked. The new Broadway store boasted a white marble, Mexican onyx, and verde bronze facade, "French ecru" walls and ceilings with gold trim, a "French ecru" carpet with rosebuds, and a French-style crystal chandelier "all modeled after the Renaissance period". (Which seems like a bit of a stretch, since ecru and gold has me thinking Louis XVI.)

|

| 1934 ad for Godissart's custom-blended face powder |

|

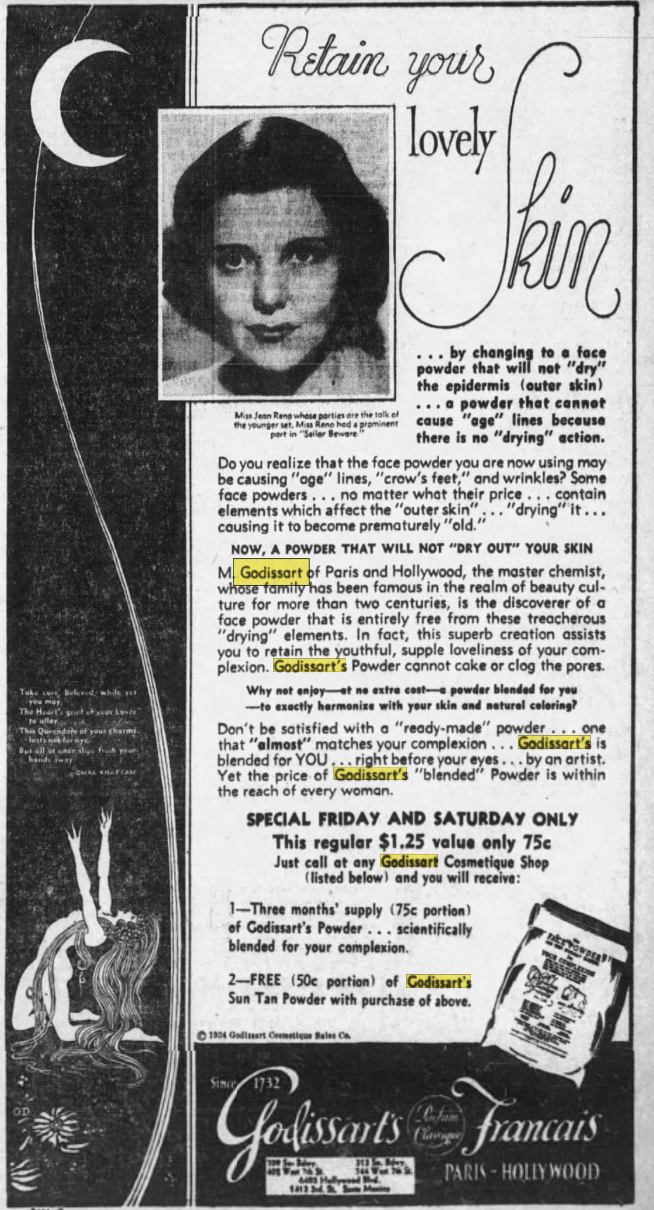

| 1934 ad for Godissart's powder, claiming it does not dry out the skin and cause age lines. |

|

| 1934 classified ad for Godissart's franchising opportunities outside of LA |

|

| 1935 article on the new Hollywood Boulevard store. |

|

| 1935 California Eagle clipping mentioning Godissart’s full line being sold at Ruth's Beauty Shop, a Central Avenue beauty shop that catered to Black women. |

|

| 1937 ad for the opening of a new Godissart's in Oakland. |

|

| 1941 ad for Vita-Cell, Godissart's latest, and perhaps last, innovation. |

Godissart's laboratory introduced a new product in 1941: Vita-Cell mouthwash.

|

| Vita-Cell ad from 1941, offering a "generous free sample". |

Joseph G. Godissart passed away in 1941, and is buried at Forest Lawn in Glendale. His second wife, Angele Cazaux Godissart, kept the business running after his death. She passed away in 1948.