When Philippe Garnier clawed his way back from bankruptcy, he commissioned three buildings in the Plaza.

The Garnier Block survives, housing part of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes.

The Garnier Building (well, part of it, anyway), survives, housing the Chinese American Museum. (Ironically, too much of the building was removed, and now it needs to be expanded.)

The 1888 Jennette Block, which was named after Philippe's wife and stood next to the Garnier Building, was torn down at the same time as the southern wing of the Garnier Building. But something that is gone need not be forgotten.

One early tenant, probably the Jennette Block's first, was inexpensive restaurant Bouillon Duval. It isn't clear if this Bouillon Duval was in any way related to the French Bouillon Duval chain or if it simply appropriated the name. Regardless, surviving newspaper ads indicate it was open for business in 1889, offering hot soup and schooner lager beer for five cents. (Schooner lager is a type of beer from eastern Canada. One wonders if the restaurant's proprietor was Québecois.)

|

Ad for Bouillon Duval restaurant, Los Angeles Herald, November 1889.

|

The 1890 city directory doesn't list the Hotel du Lion D'Or or Bouillon Duval; I surmise the hotel had not yet opened and that the restaurant (which only ran ads for two months) may have been short-lived.

Although the Jennette Block's existence had been documented earlier (such as in the 1889 ads for Bouillon Duval), it did not appear in the City Directory until 1891. The same edition of the Directory lists the Hotel du Lion D'Or in print, at 403 North Los Angeles Street (placing it squarely inside the Jennette Block). George Lacour was listed as the hotel's proprietor.

Lacour soon added another revenue stream; the 1892 directory indicates he was running Cook's Headquarters and Saloon at 401 North Los Angeles Street, also in the Jennette Block. Presumably he reopened the building's restaurant space. While he was simultaneously managing the Hotel du Lion D'Or and Cooks' Headquarters, he was also serving as Vice President of the French Benevolent Society - a very busy guy.

|

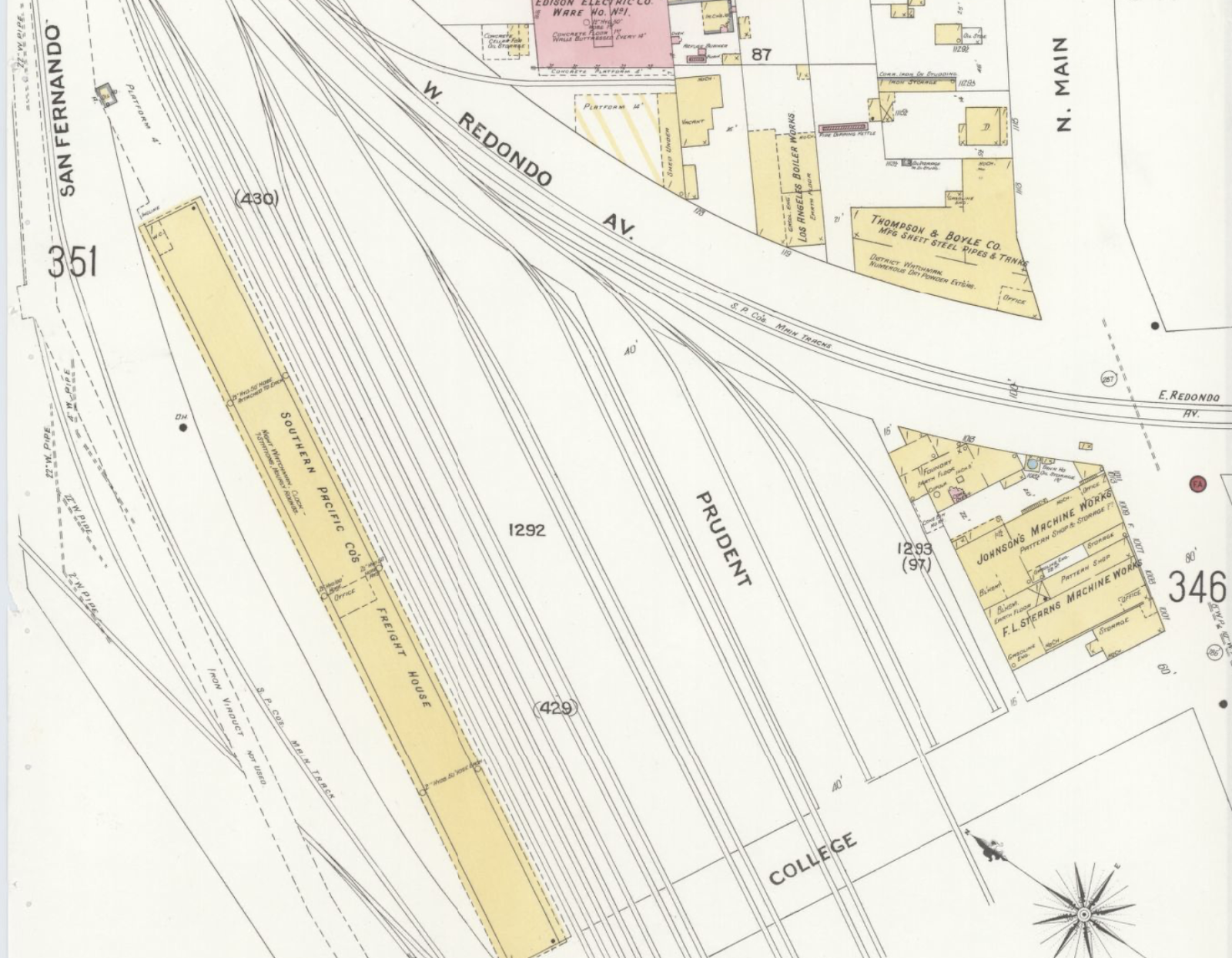

1894 Sanborn Map detail showing Jennette Block at Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets

|

This Sanborn map detail from 1894 shows the Jennette Block in its early years. At this point, it was hosting the Hotel du Lion D'Or. Today, Arcadia Street runs through where the missing wing of the Garnier Building once stood.

A Water and Power photograph states the Jennette Block was at Los Angeles and Aliso Streets, but this isn't quite correct; Aliso ended at Los Angeles Street. Arcadia was quite close, however, so it's an easy mistake to make.

George Lacour brought on his three stepsons Eugene, Frank, and Jacques Puissegur, with Eugene as the clerk and Frank and Jacques tending bar, The 1894 city directory lists another Eugene, last name Laurent, living in the hotel and waiting tables at the onsite Restaurant du Lion D'Or - presumably Cooks' Headquarters closed or changed names. 1895 saw yet another Eugene added to the hotel's personnel - Eugene Perrin, hotel cook. A second clerk must have been needed, since Miss Francoise Laffose was hired for that purpose. More cooks, Emil Gaurie, George Clausz, and Louis Ferre, came on board as well.

There was no shortage of wine and liquor stores in Victorian Los Angeles, and Lacour operated one out of the Jennette Block. Lacour would later open a second liquor store at 367 Aliso Street.

By 1896, one William Ellis was running a bootblack stand at the Jennette Block. During that year's election, the building doubled as a polling place for the city's Eighth Ward (today's council districts were a long way from existing).

Chauncey Durkee was a tall, handsome, well-dressed turfman (that is, he had worked as a bookmaking cashier) who lodged at the hotel. Since he took care of his room's upkeep himself, the hotel staff seldom went inside. One day in 1897, Lacour went to Durkee’s room to collect the rent, found the door locked, and realized no one had seen Durkee in days. Lacour forced the door open and discovered Durkee’s lifeless body on the bed, clad only in underwear. Durkee had slashed his left wrist with a razor, arranging himself so that the blood would fall into an unspecified vessel on the floor next to the bed. When Durkee bled out, the vessel overflowed, forming large pools of blood on the carpet. Blood spatter around the room and blood on Durkee’s feet suggested that he got up and walked around the room as he ended his life.

Lacour called the police, who soon discovered Durkee had left a suicide note:

Monday Morning, 11 o'clock.

To My Mother and Two Sisters:

Life without my sweetheart and brother to me is not worth living, and you are all better off with me out of the way. I love every one of you and could never be able to do anything for you, as my mind is with Clara and Charles.

Your Son and Brother,

Chauncey Durkee

Clara was Durkee's wife, who had passed away three years earlier. Charles was Chauncey's brother, who had employed him at the bookmaking firm of Durkee & Fitzgerald. Chauncey had become despondent upon Charlie's death a year earlier, and had mentioned to friends, more than once, that he was tired of life with his wife and brother gone.

The note was dated Monday morning. Lacour discovered Durkee's death on a Wednesday evening. A friend of Durkee's had come to his room on Tuesday morning, knocking on the door in vain, before finally assuming Durkee must have gone out. What a sad way to go.

Quack medicine was common during the Victorian era, and the Jennette Block was not immune. One Jean Duco Lafforge took out a rather large ad in the Los Angeles Herald in 1889 offering to be interviewed at the hotel on behalf of Prof. Joseph Fandrey, "European Specialist in Rupture Curing".

At least one of LA's many French-language newspapers,

L'Union Nouvelle, had offices in the Jennette Block for a time - a newspaper ad places it there in 1890.

John Kiefer, a German immigrant who had found success as an orchardist, vineyardist, and liquor merchant, owned several buildings including the Jennette Block at the time of his death in 1901. A few months later, hotel guest P.H. Don, who was ill and had recently been released from the San Diego County Hospital, was found dead in his bed, apparently of natural causes.

The 1902 directory listed what was at each address in the city, block by block, with the hotel at 401, then Louis Schmidt's real estate office at 403 (Schmidt also lived in the hotel for some time), then over a dozen of the Garnier Building's Chinese tenants next door including Sun Wing Wo & Co. apothecary (which has been recreated inside the Chinese American Museum), then a saloon at number 437 belonging to one Giovanetti Aladino.

Just five years after Chauncey Durkee, another long-term lodger died of suicide. Lacour and his stepsons fumigated the hotel frequently to keep it free from bedbugs, always doing so in the morning and leaving the windows open so the lodgers could safely return to their rooms at night. A bedbug-killing fluid would be poured into pans and placed on the floors of each room. The hydrocyanic gas in the formula would then dissipate and kill any bugs that might be present.

Henry Kellar, a 64-year-old cook from Lorraine, was in the habit of taking a nap in the middle of the day. Frank Puissegur stopped him on the stairs, warning him not to go into his room because of the poisonous gas. Puissegur continued on his way, but Kellar kept going down the hall, unlocked the door, and lay down.

Early that afternoon, another lodger, Ed Horst, returned to his own room and could hear Kellar struggling to breathe. Looking over a partition and seeing Kellar unconscious, Horst called for help. Lacour had to break down the door - Kellar had locked it behind him. Kellar had also closed the windows, meaning the gas could not escape the small space. The other rooms were checked for more potential victims, an act that saved the life of Harry Ruff, who had left his windows open and wasn't quite as affected as Kellar.

Both men were taken to the receiving hospital, but due to Kellar's age and the severity of his condition from a few hours of breathing in poison in a closed room, there wasn't much the doctors could do for him, and they had to focus on saving Ruff (who survived).

Three years earlier, Kellar had unsuccessfully attempted suicide by slashing his wrists. The coroner found a letter in his coat pocket addressed to Lacour and dated the previous year, stating that his brother in Lorraine would settle any debts after his death. In light of these facts, along with the locked door, closed windows, and Kellar knowing about the poison gas, his death was ruled a suicide.

By 1904, at least one Chinese merchant, Sue Chong, was doing business out of the Jennette Block. 1905 saw a barber, William Thibault, setting up shop in the hotel.

George Lacour left the hotel business to focus on his wine and liquor business with his son Frederick, turning the Hotel Du Lion D'Or over to stepsons Frank and Eugene and retiring a few years later to a ranch in La Crescenta. By 1907, the brothers had Anglicized the hotel's name to the Golden Lion Saloon. Don't let the "Saloon" part fool you; they were still running a residential hotel (long-term tenants included laborers, teamsters, a plasterer, and a clerk). Cheung Suey sold tobacco out of the storefront space at number 405 (it isn't clear if Sue Chong and Cheung Suey were the same person or two different people with similar names; print media hasn't always been careful with Asian names and it still sometimes isn't).

The Golden Lion doesn't seem to have stuck for long; by 1908 it was listed as Puissegur Brothers Saloon. Louis Schmidt was still running his real estate office out of number 403, although by this time he had moved out of the hotel. The onsite bootblack stand was now run by a Samuel Hazelwood.

By 1912, the hotel had changed hands, becoming Hotel de Paris. That year, Police Chief Charles Sebastian (who went on to become Mayor) held a special banquet honoring his executive secretary E.C. Snively and Father Edward Brady of St. Vibiana Cathedral. Brady was made a special officer for his work as a prison chaplain; Snively was honored by newspaper reporters (which happened to be his previous career).

The Mexican Revolution was going on at the time, and Americans living in Mexico were evacuated in 1912 due to unrest. Hotel de Paris' new proprietor, Frank Zucca, kindly offered free accommodation to about twenty evacuees. Chief Sebastian reported that two men believed to be spies had followed the Americans to Los Angeles and tried, unsuccessfully, to book rooms at the Hotel de Paris.

I've mentioned previously that French and Italian Angelenos often associated with each other. A 1912 Herald blurb mentions the Dante Alighieri Society (which promotes the Italian language and Italian culture) holding a banquet at the Hotel de Paris, raising $1,000 for local Italian-language schools.

Four years later, Angela Bertonne had a harrowing experience that came to an ugly head at the Hotel de Paris, where a would-be trafficker, Primo Cerbari, had brought her. The Herald quoted Sra. Bertonne thusly:

I knew Cerbari back in Italy. He found me with my husband and two children at San Francisco. He asked me many times to leave with him. I refused. Then he began to threaten me. Finally he said that unless I elope with him he would kill my children. I wanted to save them, and so I left with him. We came to Los Angeles. He began to abuse me and tried many times to force me to live a life of shame. I refused. Last night he came into the room. He had a revolver. He again asked me if I intended to obey his commands to be a woman of the streets. I answered no. Then he shot me and killed himself. I know my husband will understand. He will come to Los Angeles and take me back to our children.

1913 saw the hotel's address listed under both the Hotel de Paris and the

Cafe de Paris. Although the Zuccas were Italian, they continued to exclusively serve French food, and the cafe was popular with tourists.

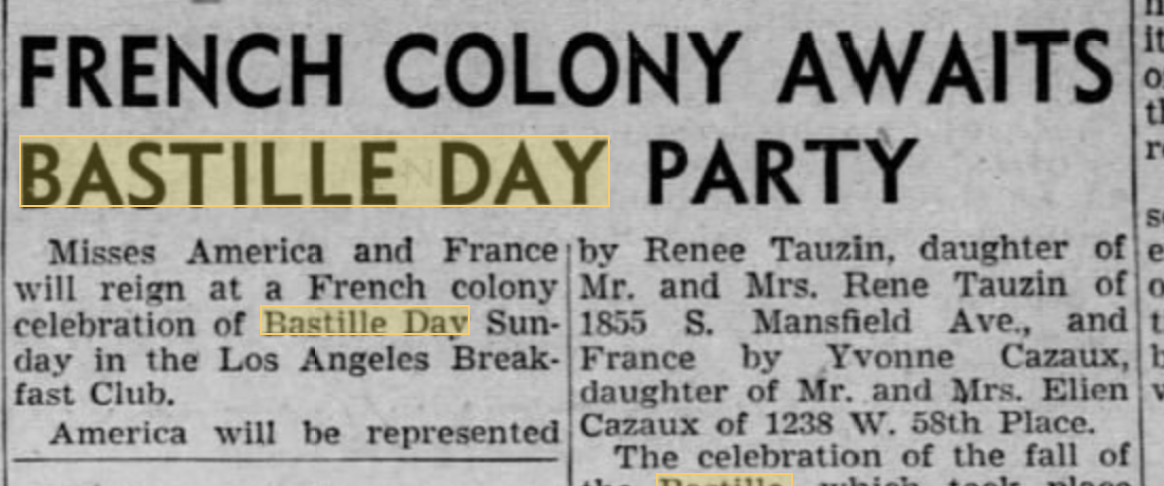

|

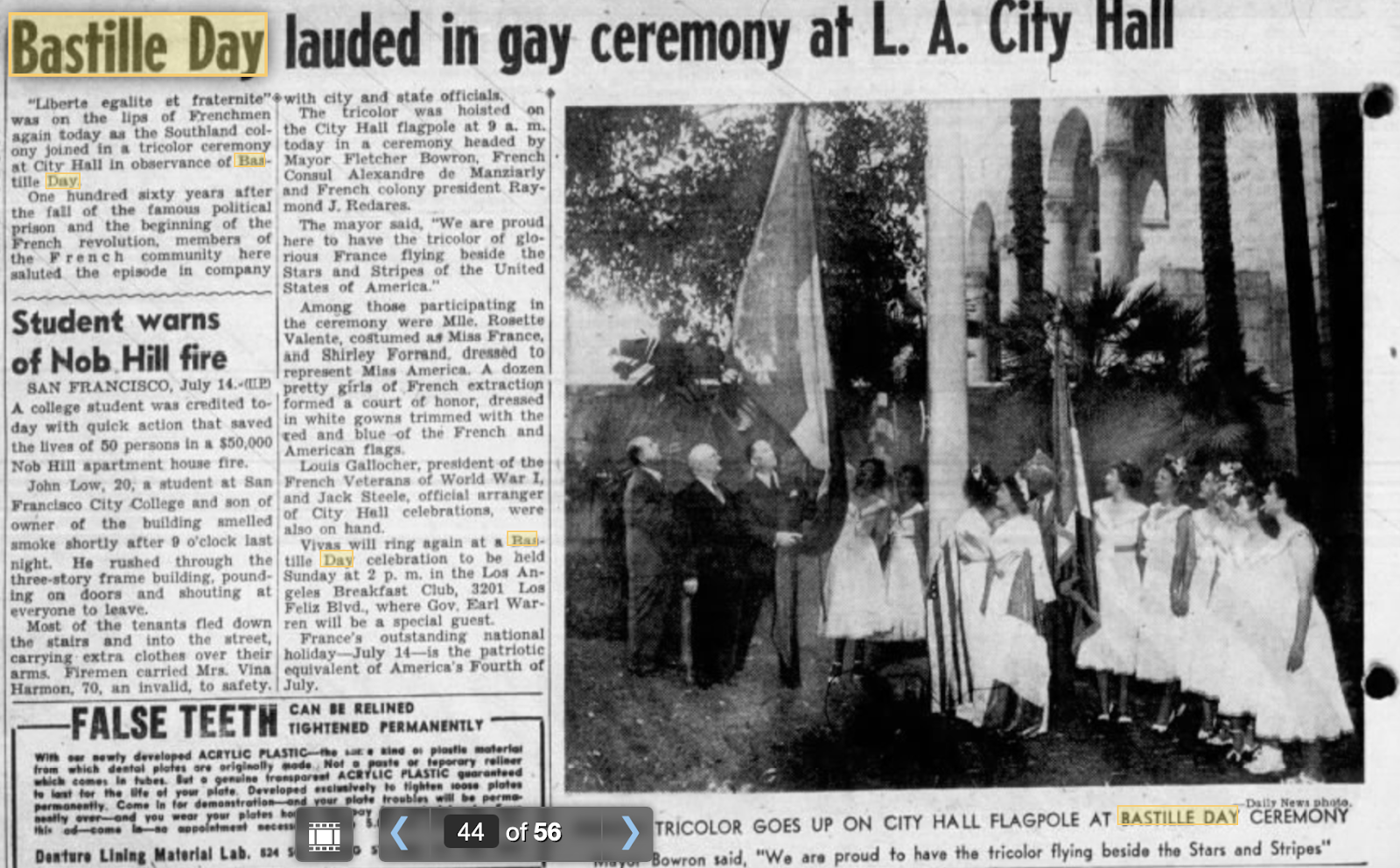

| Jennette Block with "Hotel de Paris" signage, taken around 1920 |

In 1919, Zucca's widow sold the Hotel de Paris to prominent Chinatown businessman Quan Hay, who turned it into an authentic Chinese restaurant. (Old Chinatown was more or less next door, so the Jennette Block was a logical location for a Chinese restaurant.) It was called the New Paris Cafe, at least at first. Years later, a 1935 newspaper blurb pondered "for what reason that old Chinese down on Arcadia Street named his chop suey joint the Hotel de Paris." (The name

is kind of a funny coincidence, considering that several decades earlier,

two Frenchmen and a Prussian operated a French restaurant called the Oriental Cafe, just a few short blocks away.)

Due to the fact that there were several Cafes de Paris in Los Angeles (and Hotel de Paris is a surprisingly common hotel name), it becomes very difficult to pin down the Jennette Block after the 1930s. The only thing I can state with certainty regarding its last years is that it was torn down in or around 1953 to make room for the 101.

Take a moment to contemplate this: the west wing of the Garnier Building was lopped off. If it was still there, it would extend into where Arcadia Street runs now. When you drive north on the 101 in the slower lanes and pass under the Los Angeles Street overpass, you drive right under where the Jennette Block used to stand. They say that only death and taxes are certain in life, but for Los Angeles I would add two more things: erasure and traffic.