Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Thursday, July 28, 2016

The Artist: Henri Penelon

Henri Joseph Penelon* was born in Lyon, France, around 1827. The exact date of his arrival in Los Angeles is unclear - he was not listed in the 1850 census, but Harris Newmark claimed Penelon was in the Pueblo by 1853, and tax records indicate he owned a property on Calle Principal (now Main Street) by 1856. (Surviving photographs indicate his studio was on the second floor of the Downey Block, also home to the Lafayette Hotel, on Main between First and Second.) Penelon had a business partner by the name of Adrien Davoust, who co-owned the Main Street property.

Penelon was one of the founding members of the French Benevolent Society, founded in 1860. Before the French Hospital was built in 1869, Society members helped care for the French community's ill and injured. Nowadays we'd say he did volunteer work in the community.

In 1861, heavy rains and flooding spelled disaster for the pueblo of Los Angeles. La Placita, the Plaza Church, was so badly damaged by a leaky roof that its front wall collapsed into the street. Penelon was contracted to paint the rebuilt church inside and out. And paint he did.

Henri Penelon most famously painted a mural of the Madonna and Child over the church's door, flanked by angels (probably the city's first public work of art). He lettered the church's marble tablets. He may have painted the church's ornately framed Stations of the Cross (which are consistent with his other work). He added an inscription to one of the walls: Los Fieles de Esta Parroquia á la Reina de los Angeles, 1861. (I have no idea what that means. Penelon could speak Spanish quite well, but I'm another story.)

In Harris Newmark's words, "he added some ornamental touches."(Ouch.) Supposedly, some of the Pueblo's more artistically inclined residents hated the mural and found the new church distasteful. (Ouch, again.)

To make matters worse, there was a persistent suggestion that Penelon, who made most of his living from photography, painted over photographs instead of starting with a blank canvas. While Penelon had little (if any) formal training, no one has ever produced any evidence of this ridiculous rumor being true. (And we think today's Twitter-feuding celebrities are childish jackasses...)

Surviving photographs indicate that the mural was painted over sometime between 1932 and 1937, and plastered over in 1950. A tile mosaic was installed in the same spot in 1981. The lettering on the marble tablets was visible at least as late as 1932; it isn't clear if it still dates to 1861 (the lettering would now be 155 years old; your guess is as good as mine). The Stations of the Cross are, to my knowledge, still on long-term loan to a church in Mexico. (Ouch...again and again.)

Painting murals is hard work, and Penelon was assisted at La Placita by a new arrival from France - Bernard Etcheverry, then 21 years old. We'll meet him again in a future entry.

Penelon was married to Emilia Herriot, twenty-five years younger than he was (sources disagree on whether Emilia was born in France or San Francisco, but she was certainly of French parentage). Their daughter Hortense was born in 1871, with son Honore following around 1874.

It has been said that Penelon hand-tinted photographs (a common practice until color film made tinting obsolete). Supposedly, at least one other photographer contracted with Penelon to tint his pictures. The Museum of Natural History's archive of Penelon's known photographs shows no evidence of tinting. It is certainly possible, however, that he did tinting for other photographers without necessarily tinting his own pictures (or, alternately, that his surviving pictures just didn't happen to have been tinted). Without physical evidence, we may never be completely sure.

Still, Penelon was a working artist with a family to support. It is hard to imagine that he would turn down paying work, especially if it meant not having to take so many out-of-town photography jobs. (In a situation all too familiar to today's aspiring stars, Henri Penelon took pictures to pay the bills, but his true love was painting, and as photography replaced traditional portraiture, he worked as a photographer so he could also afford to keep working as a painter. The backs of his photographs bore the stamp "H. Penelon, Artistic Gallery, Los Angeles" - which could reference either trade - along with an artist's palette.)

In an interesting twist of fate, Penelon once turned down a young Swedish photographer who applied for a job, deeming him too young and inexperienced. The photographer, Valentin Wolfenstein, set out to prove Penelon wrong - and the two later took turns working for each other.

Henri Penelon was a portrait painter. In fact, the only known painting of his that is not a portrait is an idyllic scene called The Swan and the Rabbit (interestingly, it is signed "H. Penelon 1871"; his portraits weren't signed). His other subjects were all people - nearly all from well-to-do Californio families (Penelon was fluent in Spanish and friendly with Californios, which probably helped him secure patrons).

One portrait in particular may very well be suffering from a case of mistaken identity. Long assumed to be Concepcion Arguello of Monterey, it was later assumed that she must be Concepcion Arguello of San Diego, a relative of Pio Pico. To make things even more confusing, the portrait was later identified as Feliciana Yndart by an acquaintance. A picture of Sra. Yndart in the Natural History Museum's collection is said to strongly resemble the painting, and another surviving Penelon portrait is of Jose Miguel Yndart, Feliciana's husband.

Penelon's best-known portrait, however, is likely the equestrian portrait of José Andres Sepulveda (who owned most of modern-day Orange County), astride his winning racehorse Black Swan. That portrait now belongs to the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana (if making a trip, call ahead to confirm that it is on display). As of this writing, it is the only one of Penelon's surviving works that I have seen in person.

Penelon is also credited with introducing the carte de visite to Los Angeles. Cartes de visite were tiny prints or photographs used as calling cards. In Penelon's case, at least two surviving examples were hand-painted.

Henri Penelon traveled to Prescott, Arizona on a photography assignment in 1874. He died suddenly during the trip (none of my references list a cause of death) and is buried in Prescott.

The 1880 census lists Emilia and Hortense living with relatives, with Emilia keeping their house. Curiously, I could find no reference to Honore. The 1888 city directory lists Honore as a student living in Boyle Heights (which was, at the time, LA's first suburb).

In the 1950s, Penelon's granddaughter walked into the Museum of Natural History (which was also the county Museum of Art; LACMA wasn't a separate entity yet) looking to donate two of his paintings. Less than a century after his death, none of the Museum staff knew who Henri Penelon was (OUCH!). Today, thirteen of Penelon's surviving paintings belong to the appointment-only Seaver Center for Western History Research at the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum. I sincerely hope I will be able to see them myself one day.

If you have deep pockets (or at least deeper pockets than I do), please consider sponsoring Penelon's equestrian portrait of Don Vicente Lugo. I, unfortunately, don't have that kind of money.

Want to see one of Penelon's earliest photographs? Just look at the background image for this blog. Not only is it the earliest known photograph of Los Angeles, it is credited to Penelon.

Even though his surviving works are now prized by those in the know, LA's first artist remains forgotten.

*Penelon's first name is often incorrectly written as "Honore", "Horacio", and/or "Henry"; historians searching old records for the man should make a note of this. (As someone whose first AND last names have been brutally butchered too many times to count, I am acutely aware of spelling errors when researching my own people.)

Saturday, September 30, 2017

We're Still Here, Part 5: The Natural History Museum

|

| General John C. Frémont is said to have signed the treaty ending the Mexican-American War at this humble kitchen table. |

|

| Jean-Louis Vignes' brandy still and strainer |

|

| Charles Ducommun's scales and shotgun |

|

| Original log pipe, wrapped in heavy-duty wire |

|

| Feliciana Yndart, painted by Henri Penelon |

|

| Don Vicente Lugo, painted by Henri Penelon |

|

| Don Francisco Sepulveda, painted by Henri Penelon |

|

| Animator's desk, chair, and multiplane camera - developed by Walt Disney |

|

| Beaudry Avenue on the model. |

|

| Pershing Square as it appeared before that hideous redesign in the 1950s. Do note the tiny Doughboy statue in the upper right corner. |

Saturday, June 11, 2016

The French and the Old Plaza Church

In many cities, the oldest building is likely to be a house of worship. There is some debate over what LA's oldest building is, but La Placita, or the Old Plaza Church, is certainly one of the oldest.

Before the church's dedication in December 1822, the pueblo's residents had to rely on visiting priests from the San Gabriel and San Fernando missions to have their spiritual needs met (non-Catholics began to arrive in the 1840s).

La Placita's first resident priest, believe it or not, was a Frenchman. Jean-Augustin Alexis Bachelot was born and educated in France, becoming a priest in 1820 at the age of 24. In 1827, he led the first Catholic mission to Hawaii (besides Catholicism, Bachelot introduced bougainvillea* and mesquite plants to the islands). Bachelot and his fellow priests were well-received by locals (the fact that Bachelot learned the Hawaiian language well enough to translate a prayer book and write a Hawaiian-language catechism probably helped), but they faced persecution by the Protestant regent, Queen Ka'ahumanu, who deported them from Hawaii in December 1831.

Bachelot and fellow priest Patrick Short landed near San Pedro in January 1832, traveling to Mission San Gabriel. Not only did Bachelot become La Placita's first resident priest, he served as the mission's assistant minister, temporarily led the mission when its head priest was reassigned in 1834 (turning down the substantial salary he was offered), and taught in one of LA's first schools during a teacher shortage. Besides French and Hawaiian, Bachelot spoke Spanish well (the Autry Museum of the American West has, in its collection, a photostat of a letter Fr. Bachelot wrote in 1836 - in Spanish). He was, by all accounts, well-liked by Angelenos.

Bachelot ministered in Los Angeles until 1837, when he had the opportunity to return to Hawaii. Sadly, things did not go well in Hawaii (see above), his health suffered, and he passed away later that year while at sea. Bachelot was buried off the coast of Pohnpei, Micronesia. Because of the way their priests had been treated in Hawaii, the French government intervened, and King Kamehameha III finally granted religious freedom to Catholics in Hawaii.

In Los Angeles, Bachelot was succeeded by another French priest - Reverend Anaclet Lestrade. Like Bachelot before him, he doubled as a teacher - in 1852, he taught twenty students due to lack of a proper school system (public, private, or parochial - LAUSD didn't exist until 1853). Lestrade is credited with helping to establish the first boys' boarding school in Southern California. For a time, he also held claim to the Rancho Rosa Castilla in El Sereno.

As for the building itself...the original church was destroyed due to severe flooding in 1859-1860 (the LA River burst its banks a few times - which is quite a thing to contemplate if, like me, you have only ever seen it as a tiny trickle in a vast concrete ditch). La Placita was rebuilt under the leadership of LA's popular French-Canadian mayor, Damien Marchesseault (more on him later...stock up on tissues, it's a sad story).

Henri Penelon, LA's first commercial artist and photographer, painted a mural of the Madonna and Child with two angels over the door in 1861, assisted by a new arrival, 21-year-old Bernard Etcheverry (both hailed from France, and don't worry, you'll read more about them later). Sadly, the mural - probably the first outdoor mural in Los Angeles - is long gone. In yet another example of Los Angeles erasing its own history, the mural was plastered over in 1950 (there is now a mosaic on that part of the facade, installed in 1981). The church's marble tablets bore Penelon's lettering at least as late as 1932, and the Stations of the Cross are consistent with his other work.

Although a bit beyond the topic, but worth noting, are La Placita's bells. They were cast by George Holbrook, apprentice to Paul Revere - whose father was a French Huguenot.

Let's not forget the surrounding neighborhood. In Fr. Bachelot's day, French transplant Pierre Domegue and his wife (a Chumash woman named Maria Dolores Chihuya) baked French-style sourdough bread in a low adobe that stood next to the church's courtyard. Domegue also partnered with another French baker, Andre Mano, in a bakery just around the corner (Angelenos weren't afraid of carbs yet).

La Placita is still an active parish church. Do take the time to visit, but please be respectful of those who are there for spiritual reasons.**

*Edited to add (7/1/17): A friend who reads this blog lived on Kauai for 25 years. She told me that Fr. Bachelot brought bougainvillea plants to Hawaii because they're thorny, and the Catholic Church was trying to get Native Hawaiians to wear shoes (and, for that matter, other Western garments). She describes Bachelot as "a bad, bad man" and tells me he's widely disliked in Hawaii. In the interest of presenting history in a fair and truthful manner (Native Hawaiians' stories matter too), I felt I should add the dark side of Bachelot's story. (And honestly, it sounds exactly like something the Church would have done back then.)

**Edited to add (11/9/17): I was finally able to visit La Placita when there wasn't a wedding, baptism, or other ceremony taking place. I will not, however, be adding any pictures of the interior...because I didn't take any. In spite of it being a Wednesday afternoon, there were still about 15 parishioners praying inside the church, and I refuse to disrupt someone else's religious practice. The church's interior, while on the humble side, is still beautiful and well worth seeing. Just keep any noise to an absolute minimum - this is a VERY small church with relatively high ceilings for its modest size and even the slightest noise will carry through the space. (And my sincere apologies to anyone who may have been distracted by my boot heels clicking on the tile floor. I tiptoed as much as I could.)

Thursday, July 14, 2022

Bastille Day in Old LA

On this day in 1789, the French Revolution began.

I an pretty open about having a complicated relationship with La Fête Nationale/Bastille Day. My dad is a descendant of an earlier French monarch, which makes both Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette my very distant cousins. My mom's family comes from centuries of French peasant stock.

Still, I wish I could take a time machine to Old LA on this day. The French community put on quite a Bastille Day celebration.

In fact, it used to be a pretty big deal in LA.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1881 |

One of the earliest references I can find lists the parade route: Aliso to Arcadia, Main to the Plaza, then to Spring, Spring to Second, Second to Fort (Broadway), Fort to Fourth, Fourth to Main, Main to the junction with Spring, and to the Turnverein Hall for speeches. "A representation of the Bastille" (i.e. a very early parade float) was included in the procession.

This route would have effectively started in the French Colony, gone to the Plaza, doubled back and wound through downtown, ending up where the Convention Center parking lot is today. For comparison, the Rose Parade follows a roughly 5.5 mile route.

Two of the speakers were Pascal Ganée and Georges Le Mesnager, who was quite well known for his speeches! More on that in a minute.

Bastille Day 1881 concluded with a banquet at the Pico House, prepared under one of LA's early celebrity chefs, Victor Dol.

On this day in 1882, the festivities began with a 21-gun salute at sunrise from Fort Hill. The Mayor, the President of the City Council, "delegates from fire companies and civil societies", French citizens of varying prominence, and a beauty queen - the Goddess of Liberty - all made appearances.

The Goddess of Liberty chosen for the event, by the way, happened to be 14-year-old Narcisse Sentous, eldest daughter of Jean Sentous. She was carried in a "Car of Liberty" with several maids of honor, all girls from the French Colony.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1882 (snippet of much longer article) |

The parade procession was big enough to have two divisions, both made up of prominent citizens and local societies. Besides the Car of Liberty, another car had Marie Deleval representing France, Mathilde Reynaud representing the United States, Honoré Penelon (eight-year-old son of the late Henri Penelon) dressed as the Marquis de Lafayette, and ten-year-old Auguste Lemasne dressed as George Washington. Rounding up the rear were citizens riding donkeys in tribute to the city's butchers.

Eugene Meyer, the "President of the Day" (i.e. Grand Marshal) and then-Agent for the French consulate, gave a speech in French and introduced Frank Howard (who gave a quick history lesson on Bastille Day in English). "The Star-Spangled Banner" was sung, the band played, "La Marseillaise" was sung, and Georges Le Mesnager gave a speech in French.

And that wasn't all. A large model of the Bastille had been built on Fort Hill. After the sun went down, it was stormed and set on fire. (Good thing two fire companies were there!)

The day concluded with a party at Armory Hall.

In 1886, the French Colony invited the editor of the Los Angeles Herald to attend the Bastille Day celebration. He had a prior commitment in Long Beach that day, but thanked the French Colony in the newspaper.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1886 The newspaper did still cover the event, of course. In spite of a half-hour rainstorm (an extreme rarity during a Southern California summer), the parade went on, although many people who had planned to join the parade waited inside the French Theatre for the rest of the day's events. The President of the Day was Jean-Louis Sainsevain this time - and again, one of the last speeches was given by Georges Le Mesnager. The biggest celebration of them all was held in 1889 - the 100th anniversary of the French Republic. Besides the usual festivities, an extravagant banquet and ball was held at the Pico House, then owned by Pascal Ballade and renamed the National Hotel. The speech Georges Le Mesnager gave on this day was particularly well remembered by French Angelenos - and you can read most of it (thoughtfully translated into English by the Los Angeles Herald) here. |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1891. |

An interesting footnote to the 1891 celebration is that one of the vocalists was J.P. Goytino, who despite having some musical talent was also a highly problematic newspaper editor/slumlord/all-around dirtbag. Goytino is perhaps most notorious for stopping issuance of a marriage license five years later when his extremely wealthy father-in-law, Joseph Mascarel, sought to legally marry his common-law second wife. (He needn't have bothered; Mascarel left most of his fortune to his grandchildren from his first marriage.) I could do a pretty ugly deep dive on Goytino, but David Kimbrough already did a very thorough one on Facebook (warning: it's a 12-parter).

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1900 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1901 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Hollywood Citizen-News, 1940 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1947 |

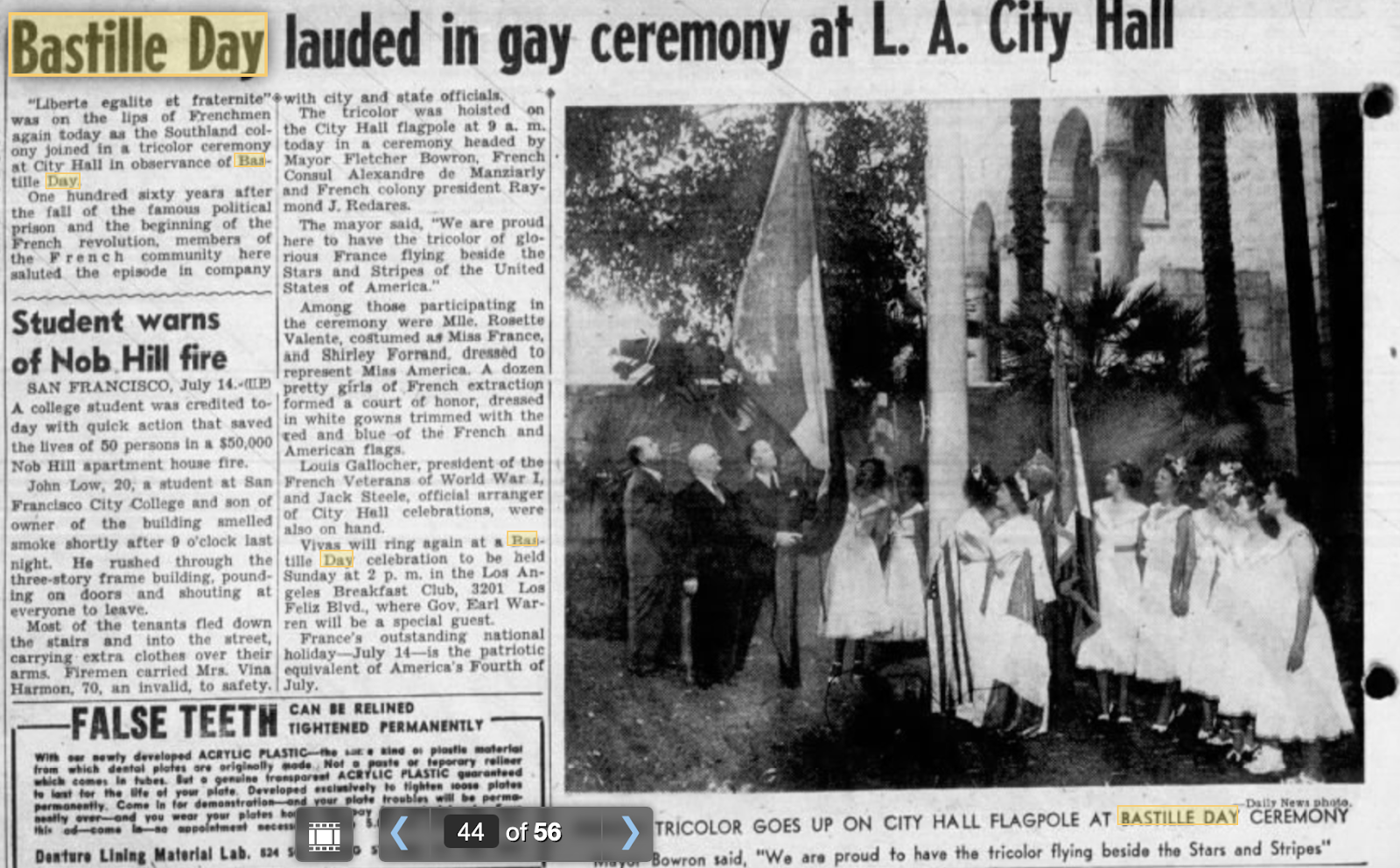

After the war, Bastille Day was back - and hosted by the Los Angeles Breakfast Club!

|

| Los Angeles Daily News, 1949 |

Los Angeles Times, 1951  |

| Los Angeles Times, 1957 |

|

| Highland Park News-Herald and Journal, 1957 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1960 |

Bastille Day was a big enough event to merit an annual flag ceremony at City Hall and draw a crowd of thousands to the Colony’s celebration. That certainly isn't the case now, and I fully expect Mayor Garcetti to ignore Bastille Day again, as Mayors of Los Angeles have tended to do for years.

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

Rest in Peace, Mr. Mayor: Damien Marchesseault

Damien Marchesseault was born in 1818 in Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, Quebec. In 1845, he left for New Orleans and became a riverboat gambler. (I should note that gambling professionally was considered socially acceptable at the time, not stigmatized as it sometimes is today.)

In 1850, Marchesseault left New Orleans for California, settling in Los Angeles. He soon partnered with another French Canadian, Victor Beaudry (whose brother, Prudent Beaudry, would also become mayor), in the ice business. In those days before refrigeration, ice had to be harvested and transported to cities to keep food from spoiling and keep drinks cold. Beaudry and Marchesseault built an ice house and operated a mule train to bring ice from the San Bernardino Mountains to Los Angeles and beyond (their customers included saloons in faraway San Francisco). Ice House Canyon, located between Mount Baldy and Mount San Antonio, is named for their ice house. In 1858, he again partnered with Beaudry, this time in the Santa Anita Mining Company.

Marchesseault also owned a saloon - and kept up his gambling skills. He became a popular local figure and was asked to run for Mayor. Which he did, winning the election and serving a one-year term in 1859-1860. (Mayors of Los Angeles served one-year terms at the time, but could serve an unlimited number of terms.)

Before long, Marchesseault's mettle was tested by disaster. The winter of 1859-1860 brought the worst rains and flooding Los Angeles had seen in many years, and the Los Angeles River shifted its bed by a quarter mile. Much of the original pueblo was destroyed.

Undaunted, Marchesseault put his considerable energy to work helping to rebuild his adopted city, including the all-important Plaza Church.

Marchesseault was elected again in 1861, serving four consecutive terms afterwards. This was a very trying time for Los Angeles - the Civil War was raging back East, the economic effects of war were felt strongly in California, a deadly measles outbreak killed a number of Angelenos, another flood destroyed the primitive water system (again), and Southern California suffered a drought so severe that farmers let their fields go fallow and ranchers had no choice but to cull many of their cattle.

Through it all, Marchesseault was applauded by Los Angeles residents for his capable management of the city. Under his tenure, the Wilmington Drum Barracks were established (just in case...), new brick buildings went up, the first Chinese market opened, the city's first public mural was commissioned from Henri Penelon, gas streetlights and telegraph wires were installed, and the Mayor himself helped organize LA's first municipal gas company (remember, this was before LA had home electricity).

In 1863, Marchesseault met Mary Clark Gorton Goodhue, who came to California from Rhode Island and had been widowed twice. She was a talented musician and spoke several languages. The Mayor and the sophisticated widow married in San Francisco in October of that year.

The onslaught of droughts, flooding, and more droughts inspired Marchesseault to seek better water management for Los Angeles. At the end of his 1865 term, he was appointed Water Overseer, a more important (and higher-paying) job than Mayor in parched Los Angeles, and served for one year.

Marchesseault temporarily served as Mayor for four months in 1867 and returned to his duties as Water Overseer before being elected Mayor again. He pushed on with improvements in the water system, awarding a contract to a business partner, engineer Jean-Louis Sainsevain. Sainsevain had been awarded the contract previously, in 1863, but gave up due to extreme difficulty and excessive costs.

Sainsevain and Marchesseault installed pipes made from hollowed-out logs, which had a frustrating tendency to leak or burst. (One of these logs, bound with metal and wire and and showing multiple splits, is displayed at the Natural History Museum’s “Becoming Los Angeles” exhibit.) By the middle of summer, stories about their water system turning the streets into muddy sinkholes were becoming all too common. Meanwhile, the fact that Sainsevain was Marchesseault's business partner did not escape notice, drawing accusations of corruption.

The Mayor was under a great strain. His administration was being harshly criticized, he had lost large amounts of money on bad investments and his partnership with Sainsevain, he had borrowed money from everyone he knew, and he was unable to repay his debts. The fact that the stress caused him to drink heavily and gamble more than ever didn't help. Mary offered to get a teaching job, but Marchesseault wouldn't hear of it.

Early in the morning of January 20, 1868, the deeply distressed Mayor entered an empty chamber at City Hall. He wrote a letter to his beloved Mary:

My Dear Mary -

By my drinking to excess, and gambling also, I have involved myself to the amount of about three thousand dollars which I have borrowed from time to time from friends and acquaintances, under the promise to return the same the following day, which I have often failed to do. To such an extent have I gone in this way that I am now ashamed to meet my fellow man on the street; besides that, I have deeply wronged you as a husband, by spending my money instead of maintaining you as it becomes a husband to do. Though you have never complained of my miserable conduct, you nevertheless have suffered too much. I therefore, to save you further disgrace and trouble, being that I cannot maintain you respectably, I shall end this state of thing this very morning. Of course, in all this, there is no blame attached - contrary you have asked me to permit you to earn money honestly by teaching and I refused. You have always been true to me. If I write these few lines, it is to set you right before this wicked world, to keep slander from blaming you in way manner whatsoever. Now, my dear beloved, I hope that you will pardon me, and also Mr. Sainsevain. It is time to part, God bless you, and may you be happy yet.

Your husband,

Damien Marchesseault.The progressive six-term Mayor then shot himself in the head with a revolver.* The next day, his suicide note appeared in the Los Angeles Semi-Weekly News and the funeral was held at his home.

Damien Marchesseault was buried in the Los Angeles City Cemetery (I surmise he was ineligible for burial at Calvary Catholic Cemetery due to his suicide). Mary remarried after his death (to Italian-born Eduardo Teodoli, who published Spanish-language newspaper La Cronica), but was buried in the City Cemetery along with Marchesseault and her son from her first marriage when she passed away in 1878.

When the old City Cemetery was taken over by the city and turned into (what else...) a Los Angeles Board of Education parking lot, surviving family members moved Mary, Marchesseault, and Mary's son C.W. Gorton to Angelus Rosedale Cemetery.

Although Marchesseault and Sainsevain were ultimately unsuccessful in their struggle to bring reliable water service to the city of Los Angeles, their successors prevailed. A few months after Marchesseault's death, Sainsevain transferred the contract to Prudent Beaudry, Solomon Lazard, and Dr. John S. Griffin. They founded the Los Angeles City Water Company, which was fittingly located at the corner of Alameda and Marchesseault Streets.

Good luck finding Marchesseault Street on a map today - it’s now Paseo de la Plaza.

There is a memorial plaque to the forgotten Marchesseault in the sidewalk outside the Mexican Consulate and Hispanic Cultural Center. The details of his service to the city are, I'm sorry to say, not listed entirely accurately on the plaque.

Some historians credit Marchesseault's leadership with turning the Pueblo into the City of Los Angeles, citing his many accomplishments and capability in rebuilding the ruined pueblo. Today, he is completely unappreciated by the city that once loved him so.

Repose en paix.

*Okay, fine...the Semi-Weekly News reported that the bullet entered the Mayor's skull next to his nose and lodged in his brain. Which is a polite way of saying he shot himself in the face (think about it...). For Mary's sake, I sincerely hope it was a closed-casket funeral.

Sunday, April 16, 2017

We're Still Here, Part 1: Olvera Street and LA's Old Pueblo

|

| Rest in peace, Mr. Mayor. And this plaque should really have a French translation... |

|

| Union Station, opposite the Pueblo. If Marchesseault Street still existed, it would lead right to Union Station's front doors. |

|

| Plaque on the wall of the Garnier building. |

|

| Do note the "P. Garnier 1890" relief. |

|

| LA's oldest Masonic hall. Sources disagree on whether Jean-Louis Sainsevain was grand master of LA's oldest lodge or not. We do know, however, that Judge Julius Brousseau was a high-ranking Mason. |

|

| The Pico House doesn't seem that big when you're right in front of it, but it looks enormous from across the plaza. French hotelier Pascale Ballade owned the Pico House for a time and threw the centennial to end all centennials here when the French Republic turned 100 in 1892. |

|

| Brunswig building (do not confuse with Brunswig Square in Little Tokyo) on the left, Garnier block (do not confuse with Garnier building) on right. |

|

| Garnier Block. |

|

| Brunswig building. |

|

| Inside the Garnier building, which now houses the Chinese American Museum. |

|

| There are too many clues to list, but there is plenty of hard evidence that much of old Chinatown was part of a French neighborhood first. |

|

| Back view of Garnier building. The building was much larger many years ago - only the last sections on the right are original. |

|

| Biscailuz building. Eugene Biscailuz, of French Basque extraction, was a respected lawman for many years in LA, and helped establish the California Highway Patrol. |

|

| La Placita and its unforgivably ugly faux-Byzantine mosaic. Up until the late 1930s, that exact spot contained LA's first public art - a mural of the Madonna and Child. The mosaic went up in 1981. (Somewhere, Henri Penelon is quietly crying into a glass of Sainsevain Brothers wine.) Oh, and let's not forget that La Placita's first TWO resident priests were from France! |

As of this writing, if you visit the old Avila Adobe on Olvera Street, you just might stumble upon something unexpected...

...an exhibit about the struggle for water services in early LA.

I had no idea it was even there. It's not advertised, and most of it is gated off. But the first part, which concerns the Sainsevains, Beaudrys, Solomon Lazard, Mayor Marchesseault (etc.), was open.

|

| Water permit signed by water overseer and mayor Damien Marchesseault. |

|

| Jean-Louis Sainsevain - engineer and Marchesseault's business partner. |

|

| Early map showing the old water system. |

|

| Jean-Louis Sainsevain's water wheel, feeding water into the Sainsevain Reservoir (now a closed-off old park called Radio Hill Gardens). |

|

| How it worked. |

|

| You had NO idea. did you? Most Angelenos don't. |

|

| The old Plaza with the original LACWC building - fittingly located on Marchesseault Street. |

|

| Bauchet Street, near Union Station. You know who Louis Bauchet is. |

|

| Classic neon sign at Philippe's. |

|

| Corner of Mesnager Street and Naud Street. You had NO idea this was here, did you? |