Sometimes, people just disappear.

It's much less common in the digital age. It would have been relatively easy to vanish without a trace - either intentionally or unintentionally - in 1919, when Jean Trébaol was last seen alive.

Born in Brest, he came to the States in 1893 at the age of 24, and soon married another Brest native, Jeanne de Kersauson de Pennendreff. The couple rented a house at 125 4th Street and would eventually have fourteen children (with thirteen surviving infancy).

Jean was a teacher and linguist, but took a job editing the French-language newspaper Le Progrès either with or under the notoriously unsavory J.P. Goytino. A squabble prompted Jean to leave and establish his own paper, Le Français. He boasted in English-language advertisements that Le Français was "the only French newspaper in Southern California established, published, and owned by a Frenchman."

This must have come as quite a surprise to Pierre Ganée, a fellow French immigrant who established, published, and owned rival paper L'Union Nouvelle.

The Herald published an article in 1897 about Constance Goytino (wife of J.P. and daughter of Joseph Mascarel) horse-whipping Mme. Trébaol outside a courtroom after a hearing. Jeanne's 17-year-old brother Robert, who was to inherit a considerable sum of money, had nominated J.P. as his legal guardian. Jeanne and her sister Isabel had concerns about Goytino's appointment. Constance also accused the Trébaols of trash-talking her. Jean sent a letter to the Herald politely informing them that Constance had attacked Jeanne unprovoked, that Jeanne had not actually taken the stand, and that "Judge Clark granted what we were intending for, namely, that Goytino as a guardian be put under heavy bonds and be restrained from incurring any liabilities on the principal of his ward."

Le Français merged with L'Union Nouvelle in 1900, and Jean went back to teaching.

With a large family to support and teacher pay being less than robust, Jean had more than one job. He taught French at Los Angeles High School, taught night classes at Polytechnic High School, taught at the Ebell Club of Pasadena, and taught privately.

He also wrote for the Herald occasionally. Of particular note is Jean's 1901 essay "The Corset Question". While Jean wasn't 100 percent correct on the history of corsets, he expressed concerns over the health effects of tightlacing and predicted - correctly - that some women would continue to wear body-shaping undergarments (although these days waist trainers and other shapewear are far more common than corsets) instead of embracing their natural shape. While he chalks this up to vanity, I surmise he was unaware of the pressure to look a certain way that many women still face, well over a century later.

In 1903, Jean suffered a breakdown from stress, overwork, and starving himself for months to feed his children. He was sent to the San Gabriel sanitarium for a few weeks to recover. A newspaper blurb solicited financial assistance for the Trébaols, who had five children by this point. (Given the date of the article and the birthdates of their children, Jeanne would have been caring for 8-month-old Yvonne and was already expecting Edouard.)

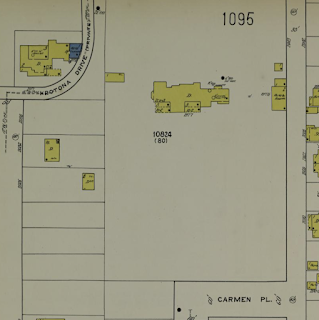

|

| 1903 blurb regarding Jean Trébaol's hospitalization due to a breakdown |

|

| Blurb regarding a subscription, or donation fund, for the Trébaols |

Jeanne was appointed legal guardian to her husband after his breakdown. A real estate transaction listed in the newspaper suggests she sold the family home on his behalf.

|

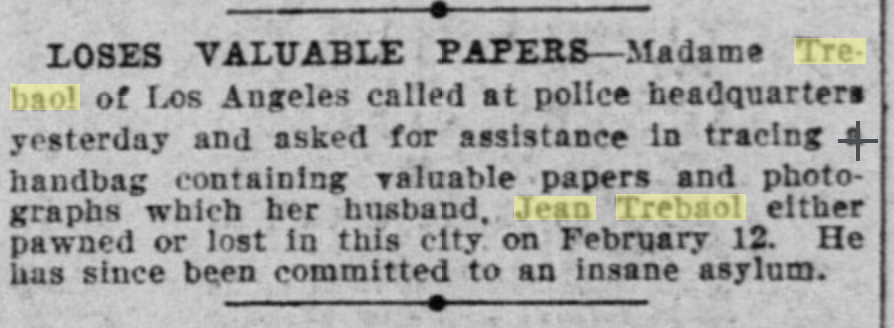

| 1909 newspaper blurb mentioning Trébaol's second hospitalization |

A snippet from one of the San Francisco papers indicates that Jean lost or pawned a bag filled with important papers and photographs (which were an expensive luxury in 1909) prior to being committed to a mental hospital again. Jeanne came to San Francisco and requested police assistance in locating the bag.

When World War One broke out in 1914, Jean tried to enlist. He was turned down due to being in his forties and having thirteen living children. (Georges Le Mesnager, by contrast, had five children, four of whom had reached adulthood.)

The Trébaols moved to Hollywood, which was still semi-rural. The family's three cows got out one day, prompting the judge to order Trébaol to keep them in another neighborhood and secure them properly.

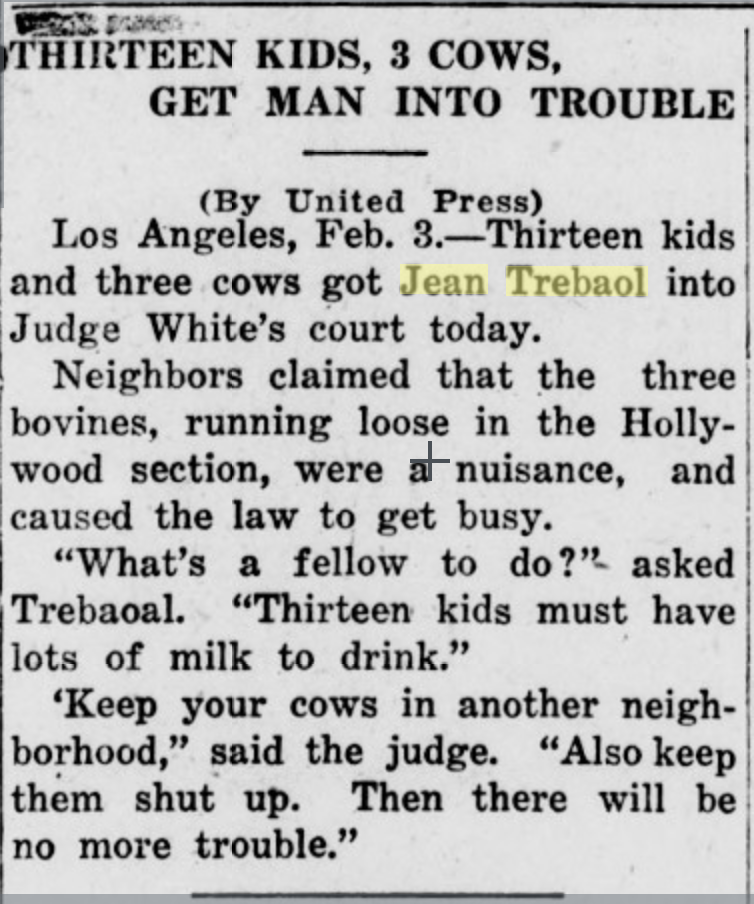

|

| 1917 blurb about the Trébaol family's cows escaping |

Jean took a job at the French Consulate for a while, then accepted a teaching post at the Mare Island YMCA in Vallejo, teaching French to sailors from the naval base bound for France. He published a small textbook related to this post. The rest of the Trébaols remained in the family home in Los Angeles.

Jean was known to the staff of the Echo de l'Ouest, one of the Bay Area's own French-language newspapers. He stopped by the newspaper's office on May 31, 1919, appearing to be severely depressed, and told the staff that he needed a complete rest. According to them, he was not himself that day.

On June 1, Jean spent the night at the home of his brother René, who lived in Vallejo. The San Francisco Call stated that he was suffering from a nervous breakdown. He vanished the following morning.

Jean Trébaol was never seen again.

One colleague noted that there was talk of him drowning, which is certainly plausible given Vallejo's location on the Bay. It was widely assumed that he must have died in either an accident or - especially in the light of his apparent depression - by suicide.

Jean never found out that he had just been selected as the Vallejo schools' French teacher.

Jeanne came up from Los Angeles to search for her missing husband, but it was to no avail.

The California Historical Society Quarterly claimed that "Mascarel offered Madame Trébaol a house of prostitution as a good source of revenue after her husband's disappearance, but she declined, especially as she would have to live in it herself!" While the French Colony was known to step up for those in need, this story isn't even possible; Joseph Mascarel had passed away twenty years earlier in 1899 at the age of 83.

Jeanne DID need money, of course. She was a mother of thirteen living children, and although her two oldest children were in their twenties, the youngest was only four years old.

Six of the Trébaol children were already "appearing in motion pictures", as the Call put it, when their father disappeared. The other seven were soon looking for acting gigs as well.

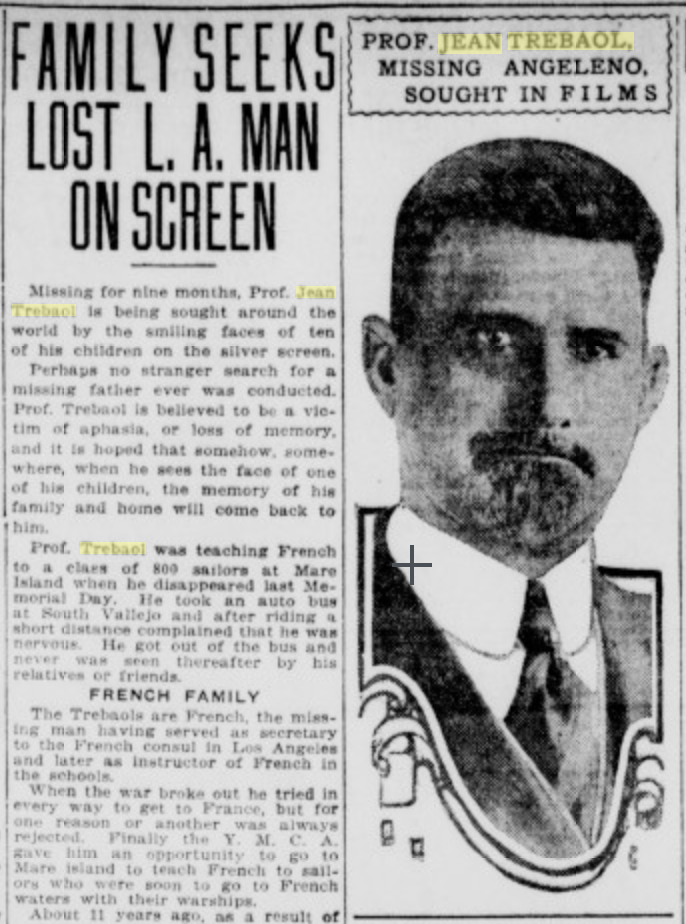

Jean had suffered from memory loss during previous mental health episodes, and had once spotted a newspaper advertisement placed by Jeanne, recovered his memory, and returned home. Besides earning money in the movies, the family hoped Jean would see and recognize one of his children on the screen.

Older brothers Hervé and Oliver went overseas (presumably to fight in the war), returning in 1919 and going on to higher education (in Hervé's case, becoming a priest and serving for years at St. Mariana in Pico Rivera). Eldest daughter Cecile helped Jeanne keep house and worked as a telephone operator at night. The other ten siblings continued to act.

|

| 1919 news article with picture of Jean Trébaol |

When he was cast as the Artful Dodger in the 1922 version of Oliver Twist, Edouard told the San Bernardino Sun that "somebody asked mother to try to get some of us in the movies and so finally mother took a few of us around to picture studios. It was hard work, walking from studio to studio, and there was very little for us then. In fact it was many weeks before we received our first call. That was for a picture with Miss Pickford. Since then, the picture directors have been very kind. After they learned about our dad...they seemed glad to give any of us work when they could. Now every one of us is in pictures. Why, even mother herself sometimes plays."

|

| 1922 picture of Jeanne with her 13 children. Headline reads "Thirteen Children Act in Movies But Want Their Daddy Not Fame." |

Out of the thirteen Trébaol children, IMDB lists acting credits for Edouard, Jeanette, François (credited as "Francis"), Philippe, Yves, and Marie. I hasten to add that in the very early days of the motion picture industry, actors were not always credited by name, and it's likely that the other children worked as extras or in uncredited roles, since Jeanne did.

In an interesting footnote, Jeanette was apparently not put off teaching by her father's struggles. A 1946 news article mentions her joining the summer school staff at San Pedro High School thirty years earlier, teaching English and Spanish. That fall, she stayed on, teaching at Polytechnic High during the day and night school in the evenings.