|

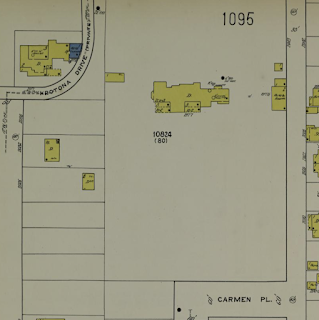

| Giroux mansion in 1919 Sanborn map |

Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

The Mining Magnate and the Monastery

Monday, November 28, 2022

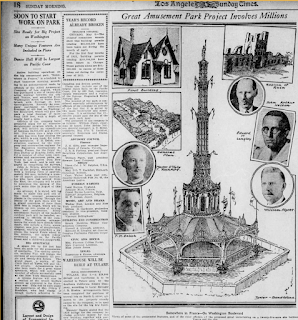

The Great French Amusement Park LA Lost

Everyone loves France. Well, most everyone does.

If France wasn't so beloved, "French girl style" wouldn't be trending on TikTok, Paris wouldn't be flooded with tourists all the time, and French food wouldn't be enjoyed around the world.

Well...Los Angeles was supposed to get what was billed as the world's largest amusement park.

It was called Somewhere in France.

|

| Former location of Somewhere in France amusement park. Note the street "Pigott Drive", named after Allied Amusements' general manager William Pigott. |

I solemnly swear on my personal copy of Le Guide Français that I am not making this up.

Construction began in May of 1923. The park's founders had hired T.H. Eslick, who had built amusements around the world (and designed the La Monica ballroom that once stood on the Santa Monica pleasure pier), to build the park. The park's art director was Edward Langley, who had directed Douglas Fairbanks' acclaimed picture "Robin Hood".

Addressing the Ebell of Pomona, Langley told the club members that the park would be beautiful, educational, and cultured, appropriate for club women or for children. (At the time, amusement parks were not necessarily kid-friendly, and could be downright seedy.)

Langley teased some of the park's features:

- The park's gate would have opened onto "a typical French street".

- A scaled-down railroad would have passed through "reproductions of cities, typical of every land, and the architecture is to be wondrous and withal authentic."

- A 90-foot mountain "which flanks one side of the park and wherein is concealed a great treasure cove of waterfalls and lily ponds and quaint scenic views is, in fact, our old friend the roller coaster."

- An onsite cinema and movie sets (Langley was a director, and Culver City is the "Heart of Screenland", after all).

- Wild animals from the Hagenbeck Zoo in Berlin (the plan was to exhibit every species of wild animal ever held in captivity).

- The largest Ferris wheel in the US.

- The largest indoor swimming pool on the Pacific Coast.

- A children's playground.

- War re-enactments (the Great War was an entirely too-recent memory).

- Some sort of water spectacle.

- A replica of France's war trenches.

- One of the largest dance halls on the Pacific Coast.

- Tea rooms and restaurants, all unique.

|

| Somewhere in France on 1924 Sanborn map with alternate name "Bohemia" |

Sunday, November 27, 2022

The French Weekly, The French Library, Pierre Prévotière, and Amaury Mars

Pierre Prévotière was an attorney from Paris.

Arriving in the US in 1900 at age 24, he made his way to Los Angeles by 1906. A newspaper excerpt stated he was in town "to study social conditions" and that he was going to establish a French library for the use of other French immigrants.

Pierre moved into the Hotel Melrose on Bunker Hill. He took a job as assistant editor of L'Avenir du Sud de la Californie ("The Future of Southern California"), a French-language weekly newspaper based in the Temple Building. (Old LA had so many French-language newspapers that I have held off on writing a separate entry about them because I know I'll have to update it, possibly over and over. I seem to unearth another newspaper at least once a year.)

|

| 1906 listing for L'Avenir newsweekly |

1906 was an election year in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Herald notes that French Angelenos were offended by a paid advertisement for S.T. Eldridge, who was running for County Supervisor (his district would have included the Second and Third Wards of Los Angeles, plus still-independent Hollywood). The Herald translates part of the advertisement thusly:

He seeks the suffrage of the French-speaking population because he is certain that he can satisfy their views concerning the free trade in wine and liquors in contrast to his opponent Dr. W.A. Lamb, who wages a determined war against the traffic.

Let us hope that he will be the candidate who shall have the voters' preference at the coming election.

The French community was insulted by the ad, and demanded an explanation from Mars. Can you blame them? Eldridge's campaign ad effectively reduced the French community to a bunch of boozers. While Prohibition did later play a role in scattering the French Colony, French Angelenos' interests have never been solely limited to their ability to produce and sell alcohol.

I'm not a journalist, but I'm pretty sure newspaper editors are supposed to remain objective.

Earlier that year, Mars joined the French Relief Committee that year, which raised funds for San Francisco earthquake survivors, although I can't say whether the sentiment was real or if it was just politically expedient to support the cause. Strangely, he was also the addressee of a suicide note left by French-Canadian printer Charles Malan. Malan checked into the Hotel St. Angelo, plugged the keyhole and doorway gaps with paper, turned on the gas, undressed, lay down on the bed, smoked a cigarette, drank two bottles of Burgundy, and waited. In the note, Malan said he was "disgusted with life and tired of being trouble to others." Malan's acquaintances stated that he was fairly successful and couldn't think of any reason for him to be suicidal (but you never really know what someone is going through).

Mars' misdeeds caught up with him in 1907.

For starters, his name wasn't Mars. He was known as Chavet in New York, then went by a different name in Mexico. Fluent in several languages, well-educated, well-traveled, highly intelligent, and adaptable, Mars may well have been an ideal con man.

Mars ran the newspaper La France in San Francisco, went to San Jose, wrote a book to commemorate President McKinley’s visit, allegedly bilked Santa Clara County out of $1500, and left town. Like so many other shysters before and after him, he came to Los Angeles.

By 1907, Mars had founded a daily paper, Progress (not to be confused with Le Progrés) and was President of the Liberal Alliance (a political organization geared towards LA's many foreign-born voters).

The working people of the Colony - druggists, grocers, butchers, saloon keepers, and so on - openly disliked Mars. People who work for a living tend to not like it when money isn't accounted for - especially when it's money they are owed.

You see, Mars was accused of selling a great deal of stock, using newly elected Mayor Harper's name to clinch the deal, and not turning in the money.

At the same time, Mars began pursuing his teenage stenographer, Madge Clark (and because this isn't creepy enough already, Mars was living in Madge's mother's boarding house). Mars was married with a daughter, and Clark was in love with a chauffeur, but that didn't deter Mars.

On the morning of March 30, 1907, Clark was speaking to the chauffeur at the corner of Franklin and New High Streets. Mars grabbed Clark, dragging her to the newspaper's upstairs office at 207 New High Street, and scolded the terrified teenager. Clark screamed. Fortunately, Justice Stephens had an office across the hall. Constable H.J. De La Monte and Deputy Charles R. Thomas responded and issued a warning.

Other people who worked in the building had noticed Mars was a little too interested in Clark, who was not at all interested in him.

Mars told the Los Angeles Times "This talk of jealousy is absurd. The girl is too young to think of being in love. I am particular about my employees being on time, and this morning she came late. That is all. There is no jealousy about it. Perhaps I was a little rough with her. She is very sensitive, hysterical, and she cried. Then the constables came. It is very unfortunate."

"Hysterical", my derrière. What's truly unfortunate is working for an abusive (and creepy!) boss, especially when they also live in your family's home.

A newspaper account briefly states that Clark ran off with the chauffeur, and wound up being detained by the police matron.

Between the fraud and the sexual harassment, Mars knew he was in trouble. He promptly skipped town, leaving his creditors in the lurch. Over a week later, he wrote to the newspaper's manager claiming he had left town to render services to the Progress Publishing Company. The rest of the paper's officials were glad to see him go, but not in the way he went, and were already taking steps to depose him (since he was technically still editor).

After the vile things he said and did, Mars had the nerve to return to Los Angeles later. Newspapers place him back in LA as early as 1921, he somehow became secretary of the French League, and he lived in LA until his death in 1927.

By 1922, he was editing yet another French newspaper, Le Courier Francais. Prohibition was now in full effect, but it was widely ignored in LA. Mars, who had vocally opposed Prohibition back in 1905, reached out to Assistant U.S. District Attorney Camarillo offering to personally ostracize any members of the French Colony who knowingly violated the Volstead Act (two Frenchmen were being held for that reason).

I'll just come right out and say it: the man wasn't just a con artist, a creep, and a fraud. He was a hypocrite, too.

Both L'Avenir and the French Library seem to have disappeared after the campaign ad controversy, and Mars' assistant editor Pierre Prévotière seems to have disappeared from Los Angeles by 1907. It isn't clear whether he finished his study on social conditions, but if anyone on either side of the ocean happens to stumble upon his work, please drop me a line. I surmise it's more enlightening than reading about his former boss' bad behavior.

Friday, November 25, 2022

Saloons, Suicides, and Chop Suey: The Long-Lost Jennette Block

When Philippe Garnier clawed his way back from bankruptcy, he commissioned three buildings in the Plaza.

The Garnier Block survives, housing part of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes.

The Garnier Building (well, part of it, anyway), survives, housing the Chinese American Museum. (Ironically, too much of the building was removed, and now it needs to be expanded.)

The 1888 Jennette Block, which was named after Philippe's wife and stood next to the Garnier Building, was torn down at the same time as the southern wing of the Garnier Building. But something that is gone need not be forgotten.

One early tenant, probably the Jennette Block's first, was inexpensive restaurant Bouillon Duval. It isn't clear if this Bouillon Duval was in any way related to the French Bouillon Duval chain or if it simply appropriated the name. Regardless, surviving newspaper ads indicate it was open for business in 1889, offering hot soup and schooner lager beer for five cents. (Schooner lager is a type of beer from eastern Canada. One wonders if the restaurant's proprietor was Québecois.)

|

| Ad for Bouillon Duval restaurant, Los Angeles Herald, November 1889. |

The 1890 city directory doesn't list the Hotel du Lion D'Or or Bouillon Duval; I surmise the hotel had not yet opened and that the restaurant (which only ran ads for two months) may have been short-lived.

Although the Jennette Block's existence had been documented earlier (such as in the 1889 ads for Bouillon Duval), it did not appear in the City Directory until 1891. The same edition of the Directory lists the Hotel du Lion D'Or in print, at 403 North Los Angeles Street (placing it squarely inside the Jennette Block). George Lacour was listed as the hotel's proprietor.

Lacour soon added another revenue stream; the 1892 directory indicates he was running Cook's Headquarters and Saloon at 401 North Los Angeles Street, also in the Jennette Block. Presumably he reopened the building's restaurant space. While he was simultaneously managing the Hotel du Lion D'Or and Cooks' Headquarters, he was also serving as Vice President of the French Benevolent Society - a very busy guy.

|

| 1894 Sanborn Map detail showing Jennette Block at Arcadia and Los Angeles Streets |

This Sanborn map detail from 1894 shows the Jennette Block in its early years. At this point, it was hosting the Hotel du Lion D'Or. Today, Arcadia Street runs through where the missing wing of the Garnier Building once stood.

A Water and Power photograph states the Jennette Block was at Los Angeles and Aliso Streets, but this isn't quite correct; Aliso ended at Los Angeles Street. Arcadia was quite close, however, so it's an easy mistake to make.

Monday Morning, 11 o'clock.To My Mother and Two Sisters:Life without my sweetheart and brother to me is not worth living, and you are all better off with me out of the way. I love every one of you and could never be able to do anything for you, as my mind is with Clara and Charles.Your Son and Brother,Chauncey Durkee

I knew Cerbari back in Italy. He found me with my husband and two children at San Francisco. He asked me many times to leave with him. I refused. Then he began to threaten me. Finally he said that unless I elope with him he would kill my children. I wanted to save them, and so I left with him. We came to Los Angeles. He began to abuse me and tried many times to force me to live a life of shame. I refused. Last night he came into the room. He had a revolver. He again asked me if I intended to obey his commands to be a woman of the streets. I answered no. Then he shot me and killed himself. I know my husband will understand. He will come to Los Angeles and take me back to our children.

Tuesday, September 6, 2022

What Is Going On with the Culver Chateau?

|

| The Culver Chateau |

Tuesday, August 2, 2022

Charles Chandeau Gets Caught

Although I don’t often tell the tales of people who were only briefly in LA, this one was too good not to share.

Every year, Hollywood hopefuls come to LA with stars in their eyes - in fact, one of my grandparents and their siblings tried to get into silent movies. None of them succeeded, although one did some background work, one had a stint as a horror star’s chauffeur, and another was married to a working actor.

Most dreamers either get regular jobs or go home when they don’t make it. At least one failed entertainer turned to nefarious means instead.

Charles Chandeau, aka Deschnau, aka Chenault, left Quebec for the West Coast in 1920, stopping in Victoria (BC), Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco before landing in LA. (Note: the LA Public Library and Calisphere both give his surname as Deschnau. However, Canadian military records indicate his legal name was Chandeau.)

Chandeau was an actor, but not a successful one. He had never had much money, but he did have a very particular skill set. One that made him a potential nightmare to to the city’s elite.

For years and years, the 50-year-old Chandeau had trained to be a magician. It’s well known that magicians (good ones, not the Gob Bluths of the profession) are masters of sleight-of-hand, misdirection, and illusion.

He had also spent half of his life studying criminal masterminds, plotting a caper that would baffle the authorities.

Chandeau opened two safety deposit boxes in LA, probably for the purposes of casing the banks.

Chandeau owned a rather large trunk. It looked like an ordinary trunk. In fact, it was a carefully modified magician’s trunk that Chandeau had originally intended for theatrical use.

Although Chandeau was clever, he was also arrogant enough to think he wouldn’t get caught. And, like Gob Bluth, he made a huge mistake..

Chandeau needed an accomplice. He took out a classified ad in the newspaper, stating “WANTED - one who can rough it. He may be down and out, but must have left plenty of pep.” Chandeau was inundated with replies from men and boys who clearly understood the ad’s subtext. Detectives found ample proof of this when searching his hotel room.

Someone sent an anonymous tip to the Los Angeles Herald, which put noted private detective Nick Harris on the case.

Chandeau selected Earl Wilson from the stack of respondents. Wilson was just 18, had left home due to family problems, and a broken shoulder had put him out of work.

The plan was simple enough. Chandeau would hide inside the trick trunk, Wilson would have it stored inside the vault at the Hollywood Fireproof Storage Company on Highland Avenue (where early Hollywood’s elite stashed their valuables), and when the employees left, Chandeau would let himself out and loot the place.

Unfortunately for Chandeau and Wilson, detectives had traced him to a hotel in then-fashionable Westlake and a second hotel on Flower Street. His room was bugged, and detectives could hear the entire plot unfold.

Chandeau rented a room on Wilcox, visited the storage facility, and spoke with the manager about rates, leaving a box of “valuables” that really contained shredded paper. He claimed to have a trunk full of ore that he would bring over the next day, stating that he wasn’t sure how long he’d be in town and that he might need to store it for a day or a month.

Wilson hired a transfer man (i.e. mover) to move the trick trunk to the rented room, then hired a second transfer man to move the trunk to the facility the next day. The trunk arrived just before the warehouse closed.

Detectives were watching.

Chandeau had stocked the trunk with flashlights, wires, tools, skeleton keys, metal files, first aid supplies (in case of rough handling), a bottle of water, oranges, sandwiches, cookies, and candy.

And, finally, a pair of kid gloves. Chandeau wanted to be sure he wouldn’t leave any prints.

|

| Front page of the Evening Examiner, June 23, 1920. |

Wilson was arrested while walking away from the storage facility. When confronted with details of the plot, he admitted Chandeau was in the trunk.

Besides assuming he wouldn’t get caught, Chandeau had made another crucial error: while the trunk was modified to allow for air supply, the vault was airtight when sealed for the night, and the facility sprayed disinfectant.

Had detectives not raided the vault as quickly as they did, Chandeau could easily have died of suffocation.

But detectives did indeed open the vault, accompanied by Evening Herald reporter Fred Woodward. Knocking on the trunk, Harris announced “Come on out, Charlie.”

The jig was up. The lock popped open, the clamps came off, the trunk popped open, and Chandeau’s balding head popped out. Chandeau was so short of breath he could hardly gasp “Hello. How did you know I was here?”

|

| Chandeau’s trunk on display |

Chandeau was granted permission to speak with Wilson and told him “I am sorry I got you into this.” When asked why he would lead an 18-year-old into crime, he replied “Well, you can trust a boy not to squeal, but you cannot trust a man.” (I couldn’t help reading this in Gob’s voice.)

Recounting Chandeau’s failed scheme in the paper, Woodward claimed “The most astonished man I ever saw in my life was Charles Chandeau, alias Deschneau, when we opened the trick trunk and foiled a campaign of robbery that would have amazed and mystified the police of the entire country. Chandeau was so surprised at being discovered and ordered out of the trunk that he could barely gasp. The expression on his face was so tragic that it was almost ludicrous.”

Chandeau came clean, and even spoke highly of the detectives who arrested him: “During the years that I read criminal stories I formed the opinion that all police officers were ruffians. I was surprised when you treated me with kindness.” (Boy, LA has changed since 1920.)

Chandeau, dubbed the “Jack-in-the-box burglar” or the “trick trunk burglar” in the press, faded into obscurity after his burglary trial. A woman claiming to be his sister contacted authorities, stating the family had been looking for him ever since he left to serve in World War One (shades of Jean-Louis Vignes). Wilson fell ill and died before the trial.

As for Harris, he ran for Mayor in 1923 on an anti-crime platform. Nick Harris Detectives is still active to this day.

Is it just me, or would this story make a great heist comedy (ideally with Will Arnett playing Chandeau)? Or have I just watched “Arrested Development” way too many times?

Thursday, July 14, 2022

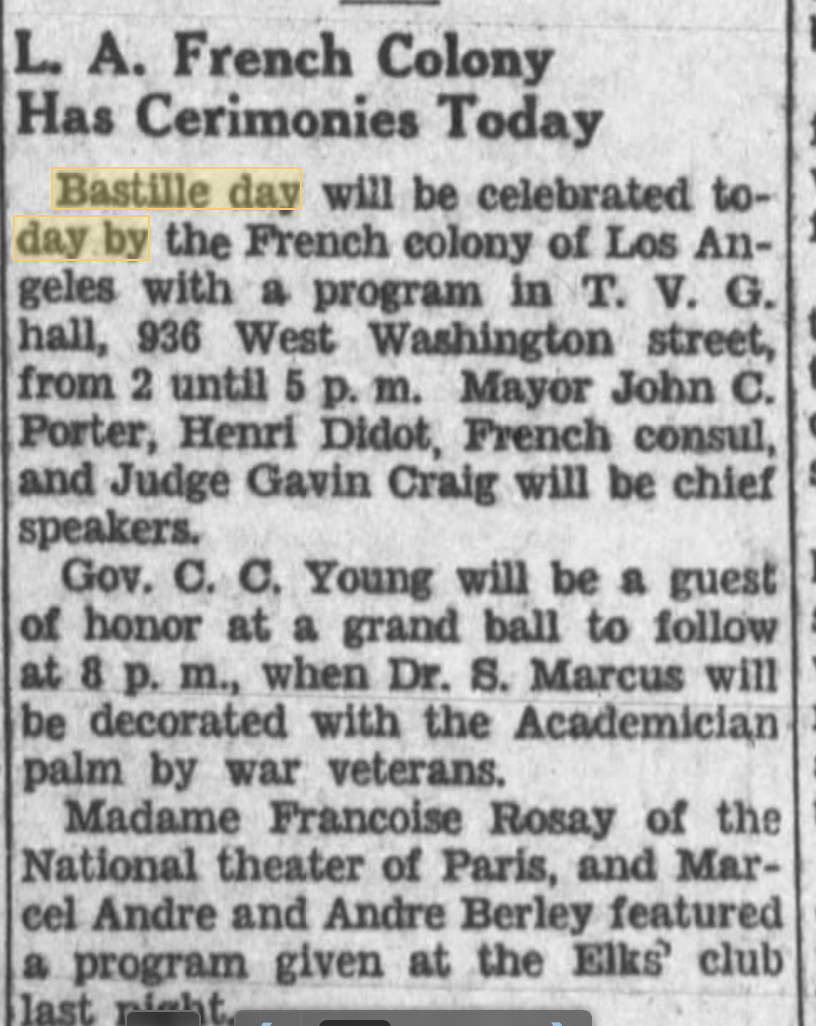

Bastille Day in Old LA

On this day in 1789, the French Revolution began.

I an pretty open about having a complicated relationship with La Fête Nationale/Bastille Day. My dad is a descendant of an earlier French monarch, which makes both Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette my very distant cousins. My mom's family comes from centuries of French peasant stock.

Still, I wish I could take a time machine to Old LA on this day. The French community put on quite a Bastille Day celebration.

In fact, it used to be a pretty big deal in LA.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1881 |

One of the earliest references I can find lists the parade route: Aliso to Arcadia, Main to the Plaza, then to Spring, Spring to Second, Second to Fort (Broadway), Fort to Fourth, Fourth to Main, Main to the junction with Spring, and to the Turnverein Hall for speeches. "A representation of the Bastille" (i.e. a very early parade float) was included in the procession.

This route would have effectively started in the French Colony, gone to the Plaza, doubled back and wound through downtown, ending up where the Convention Center parking lot is today. For comparison, the Rose Parade follows a roughly 5.5 mile route.

Two of the speakers were Pascal Ganée and Georges Le Mesnager, who was quite well known for his speeches! More on that in a minute.

Bastille Day 1881 concluded with a banquet at the Pico House, prepared under one of LA's early celebrity chefs, Victor Dol.

On this day in 1882, the festivities began with a 21-gun salute at sunrise from Fort Hill. The Mayor, the President of the City Council, "delegates from fire companies and civil societies", French citizens of varying prominence, and a beauty queen - the Goddess of Liberty - all made appearances.

The Goddess of Liberty chosen for the event, by the way, happened to be 14-year-old Narcisse Sentous, eldest daughter of Jean Sentous. She was carried in a "Car of Liberty" with several maids of honor, all girls from the French Colony.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1882 (snippet of much longer article) |

The parade procession was big enough to have two divisions, both made up of prominent citizens and local societies. Besides the Car of Liberty, another car had Marie Deleval representing France, Mathilde Reynaud representing the United States, Honoré Penelon (eight-year-old son of the late Henri Penelon) dressed as the Marquis de Lafayette, and ten-year-old Auguste Lemasne dressed as George Washington. Rounding up the rear were citizens riding donkeys in tribute to the city's butchers.

Eugene Meyer, the "President of the Day" (i.e. Grand Marshal) and then-Agent for the French consulate, gave a speech in French and introduced Frank Howard (who gave a quick history lesson on Bastille Day in English). "The Star-Spangled Banner" was sung, the band played, "La Marseillaise" was sung, and Georges Le Mesnager gave a speech in French.

And that wasn't all. A large model of the Bastille had been built on Fort Hill. After the sun went down, it was stormed and set on fire. (Good thing two fire companies were there!)

The day concluded with a party at Armory Hall.

In 1886, the French Colony invited the editor of the Los Angeles Herald to attend the Bastille Day celebration. He had a prior commitment in Long Beach that day, but thanked the French Colony in the newspaper.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1886 The newspaper did still cover the event, of course. In spite of a half-hour rainstorm (an extreme rarity during a Southern California summer), the parade went on, although many people who had planned to join the parade waited inside the French Theatre for the rest of the day's events. The President of the Day was Jean-Louis Sainsevain this time - and again, one of the last speeches was given by Georges Le Mesnager. The biggest celebration of them all was held in 1889 - the 100th anniversary of the French Republic. Besides the usual festivities, an extravagant banquet and ball was held at the Pico House, then owned by Pascal Ballade and renamed the National Hotel. The speech Georges Le Mesnager gave on this day was particularly well remembered by French Angelenos - and you can read most of it (thoughtfully translated into English by the Los Angeles Herald) here. |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1891. |

An interesting footnote to the 1891 celebration is that one of the vocalists was J.P. Goytino, who despite having some musical talent was also a highly problematic newspaper editor/slumlord/all-around dirtbag. Goytino is perhaps most notorious for stopping issuance of a marriage license five years later when his extremely wealthy father-in-law, Joseph Mascarel, sought to legally marry his common-law second wife. (He needn't have bothered; Mascarel left most of his fortune to his grandchildren from his first marriage.) I could do a pretty ugly deep dive on Goytino, but David Kimbrough already did a very thorough one on Facebook (warning: it's a 12-parter).

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1900 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1901 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Hollywood Citizen-News, 1940 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1947 |

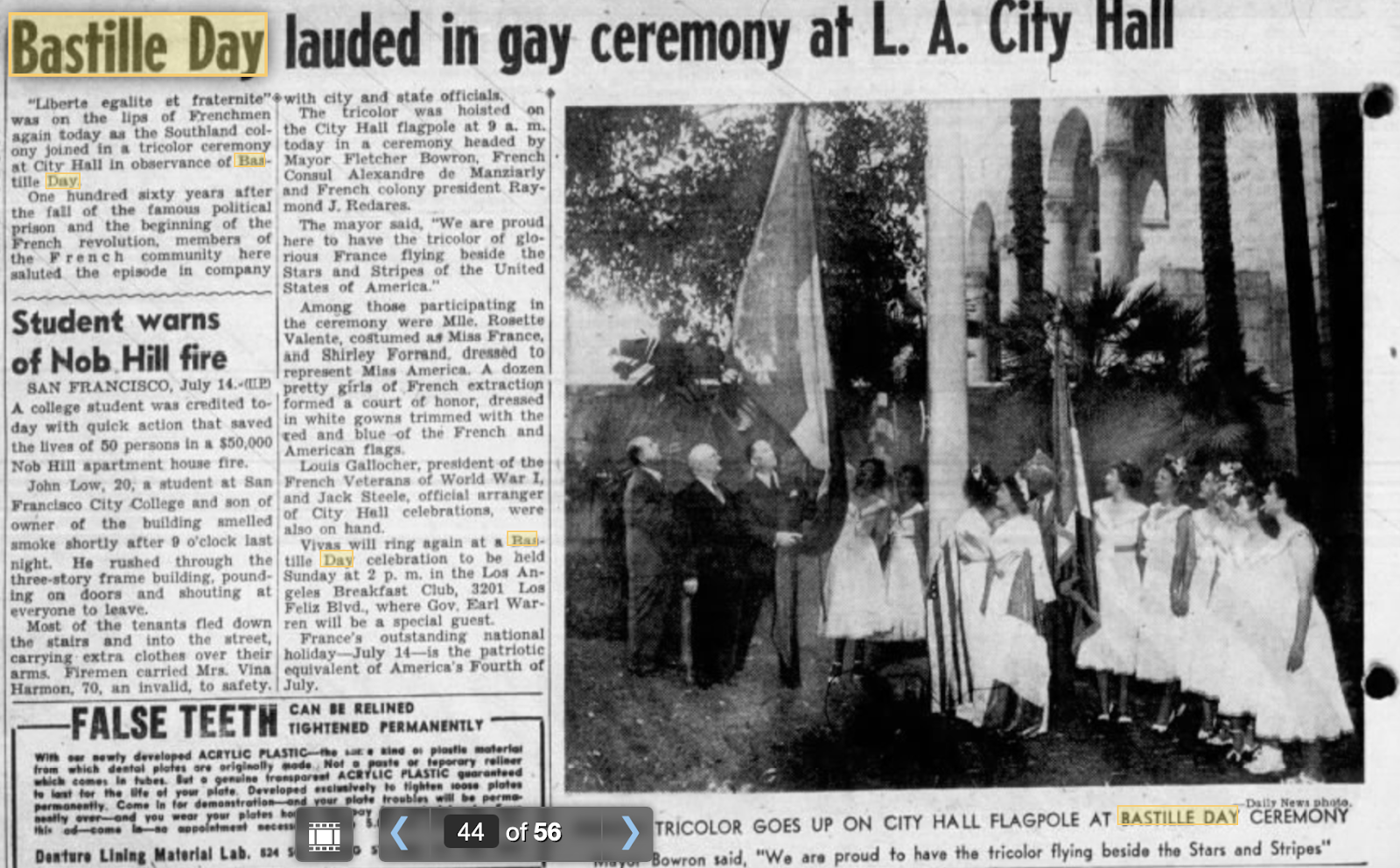

After the war, Bastille Day was back - and hosted by the Los Angeles Breakfast Club!

|

| Los Angeles Daily News, 1949 |

Los Angeles Times, 1951  |

| Los Angeles Times, 1957 |

|

| Highland Park News-Herald and Journal, 1957 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1960 |

Bastille Day was a big enough event to merit an annual flag ceremony at City Hall and draw a crowd of thousands to the Colony’s celebration. That certainly isn't the case now, and I fully expect Mayor Garcetti to ignore Bastille Day again, as Mayors of Los Angeles have tended to do for years.