Last weekend, I gave a presentation on the French in Southern California at San Diego Mensa's Regional Gathering in Palm Springs (video coming soon - IF I can get the darn thing uploaded).

The first, and most revealing, question in the Q&A concerned why LA's historically French neighborhoods are now associated with other ethnic groups.

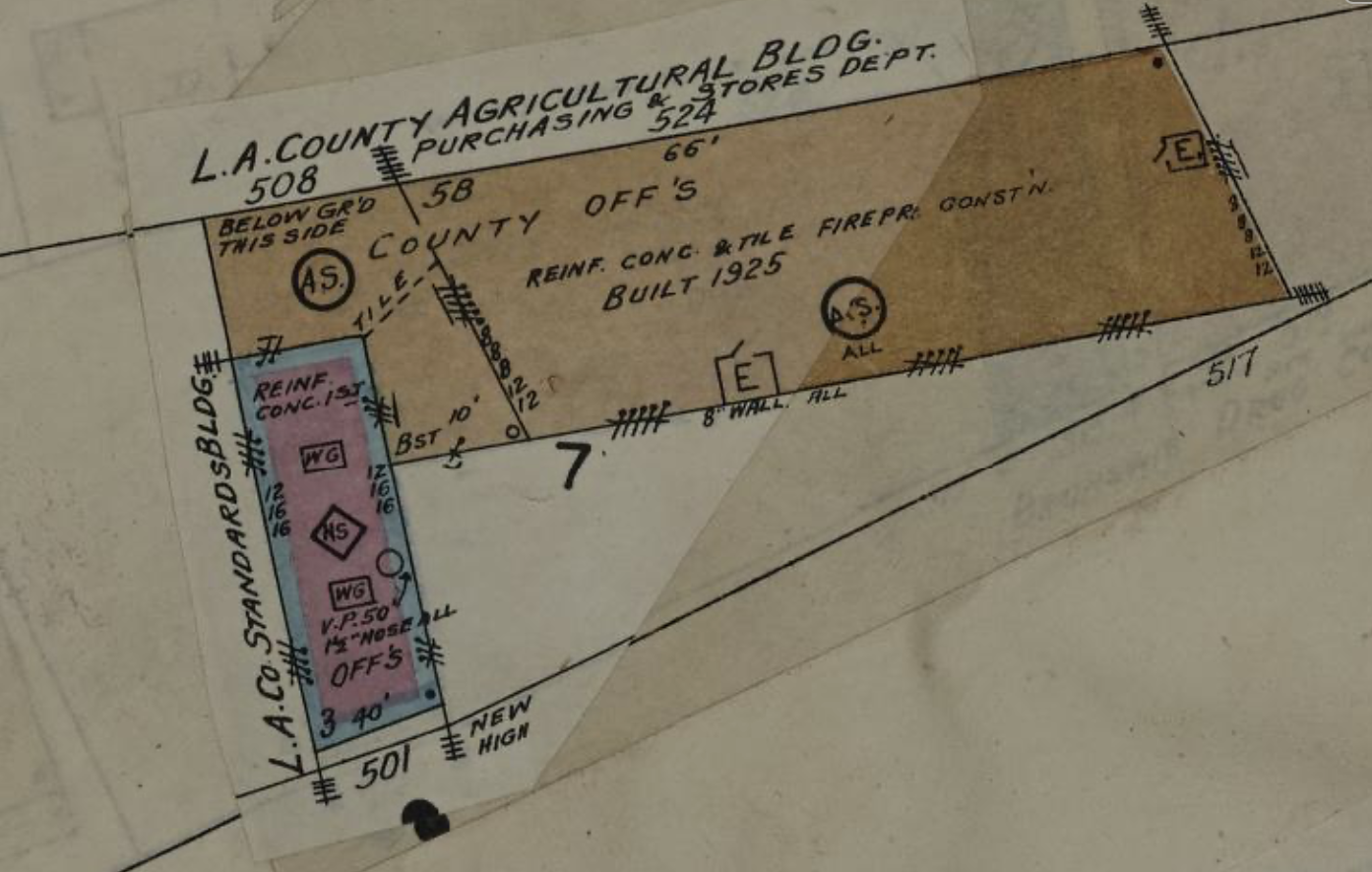

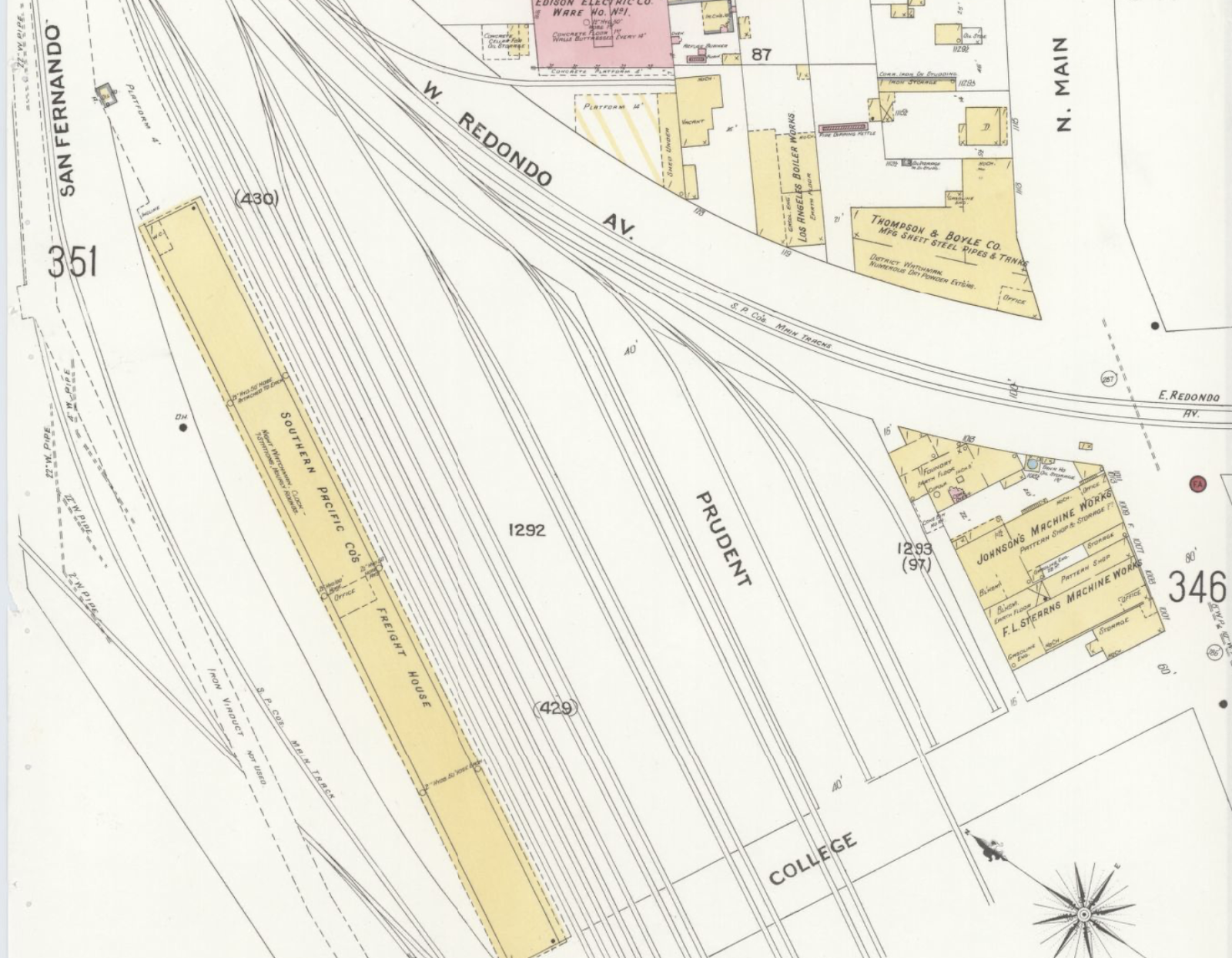

The original Frenchtown - bordered by Main Street, 1st Street, Aliso Street, and the LA River - is now largely split between Little Tokyo and the industrial core, with the Civic Center bleeding into the northern end of the neighborhood.

As Frenchtown expanded to the north, it grew to include modern-day Chinatown. Why is Joan of Arc standing outside Chinatown's only hospital?

Because it was the French Hospital until 1989, and until the 1930s, it was a French neighborhood. Naud Junction, the Fritz houses, and Philippe the Original (creators of the French Dip sandwich; in that location since 1951) are all in Chinatown for the very simple reason that

it wasn't always Chinatown. (LA's original Chinatown was demolished in 1931 to build Union Station - long after

the Sainsevain brothers lost their uncle's vineyard).

Pellissier Square is now called Koreatown. Why? Because much of central LA declined after the 1930s, making it an affordable place for Korean immigrants to live and start businesses by the time the Korean War ended.

They weren't the first Koreans in Los Angeles. Historically, Korean Angelenos tended to live in Bunker Hill.

(Incidentally, "Koreatown" is something of a misnomer. HALF of Koreatown residents are Latino, and only about one-third are Asian. Korean Angelenos do, however, account for most of the area's businesses.)

There are still clues to Koreatown's French origins. Normandie Avenue, one of the longest streets in Los Angeles County (stretching 22.5 miles between Hollywood and Harbor City), runs smack down the middle of Koreatown.

The Pellissier Building, including the legendary Wiltern Theatre, proudly towers over Wilshire and Western. And if you look at the neighborhood's architecture - sure, it's largely Art Deco, but some of it is also French-influenced.

In the early days, Los Angeles was a fairly tolerant place. It wasn't a utopia by any means (case in point: the Chinese Massacre of 1871), but Los Angeles was more tolerant of non-WASPs than most North American cities.

By the 1920s, a plague began to infest Los Angeles on a grand scale.

Deed restrictions.

Sometimes called restrictive covenants, deed restrictions barred ethnic and/or religious groups from buying homes in particular areas.

Why? Who would do something so hateful?

Let's start by rewinding the clock to the 1850s.

In 1850, California became a state. Legally, Los Angeles should have started opening public schools at this point (due to separation of church and state), but LAUSD wasn't founded until 1853. By this time, there was a growing number of Protestant families - most of them Yankees - in town. The few schools that did exist in the area were all Catholic, and Protestant parents objected - loudly - to the idea of sending their kids to Catholic schools. (Many Catholic schools do accept non-Catholic students, and many non-Catholic parents may prefer them if the local public schools aren't good enough. But things were a little different 164 years ago.)

Fast-forward to the 1880s.

When railroads first connected Southern California to the rest of the United States, newcomers flooded the area. Most were WASPs, and the majority were from the Midwest.

Guess where else deed restrictions were common? That's right - the WASPy Midwest. (No offense to any WASPs or Midwesterners who may read this, but I don't believe in hiding the truth. I sure as hell have

never pretended French Californians were

perfect.)

Before too long, deed restrictions barred people of color from much of the city.

Some even excluded Jews, Russians, and Italians. Homeowners' associations and realtors often worked together to keep restricted neighborhoods homogeneous. (My skin is crawling as I write this.)

Excluded ethnic and religious groups, therefore, tended to live in areas that weren't restricted against them.

French Angelenos, however, were a pretty tolerant bunch.

The first baker in the city to make matzo was Louis Mesmer, who was Catholic. His daughter Tina married a Protestant.

Harris Newmark - German and Jewish - was one of Remi Nadeau's best friends.

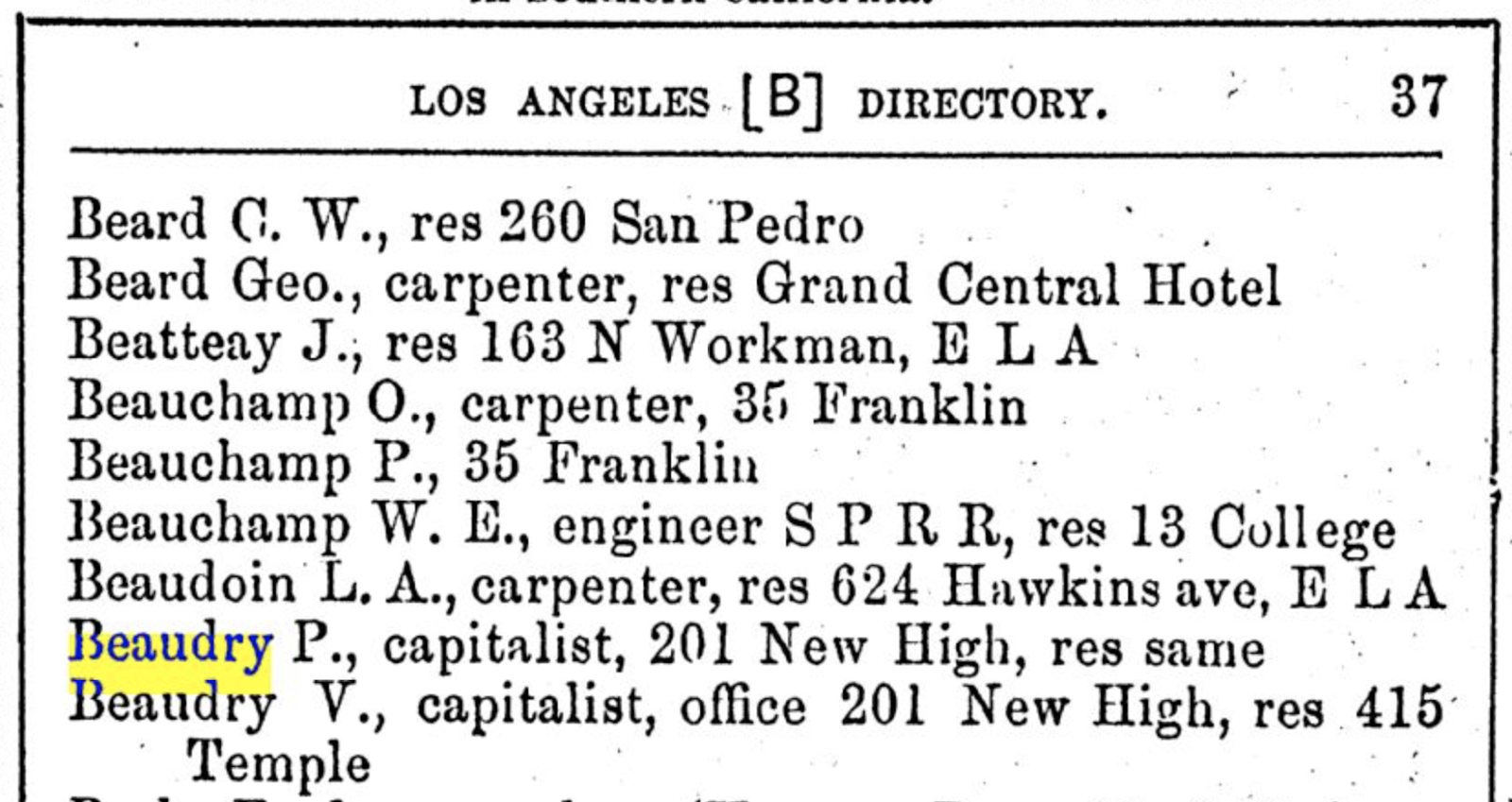

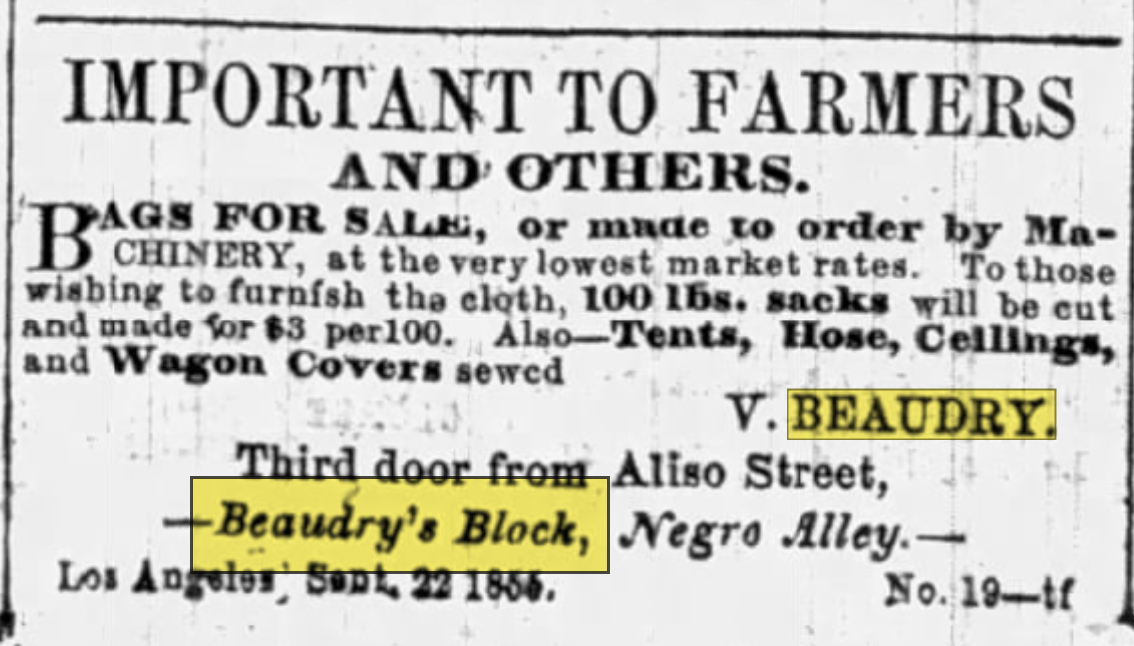

Prudent Beaudry's sometime business partner Solomon Lazard - French and Jewish - was so popular among Angelenos of

all ethnicities that Spanish speakers called him "Don Solomon".

French Basque

Philippe Garnier built a commercial building specifically to lease it to Chinese merchants, who weren't considered human beings by the United States government at the time.

No one batted an eye at the fact that quite a few of LA's earlier Frenchmen (including

Louis Bauchet,

Joseph Mascarel, and Miguel Leonis) married Spanish, Mexican, or Native American women.

Frenchtown didn't have deed restrictions. (It's true that we don't always get along with everyone, but you won't find many French people willing to do something that asinine.)

The original core of Frenchtown was largely taken over by the civic center and industry when the area was redeveloped in the 1920s (and when the 101 sliced through downtown). But part of it became Little Tokyo. Why?

No deed restrictions.

In fact, when Japanese American internment emptied Little Tokyo during World War II, African Americans (many working in the defense industry) poured into the neighborhood, and for a time it was known as "Bronzeville". Again,

it was still one of the few areas with no deed restrictions. (On a personal note, the original paperwork for my childhood home in Sherman Oaks - built in 1948 - included a restriction against selling to African Americans.

No other ethnicities were excluded. Which should give my dear readers a rough idea of what African American home buyers faced at the time - and renters had even fewer choices. Deed restrictions were legally struck down in California in 1947 and nationwide in 1948, but in Los Angeles, they persisted into the 1950s. Nationwide, it was probably worse.)

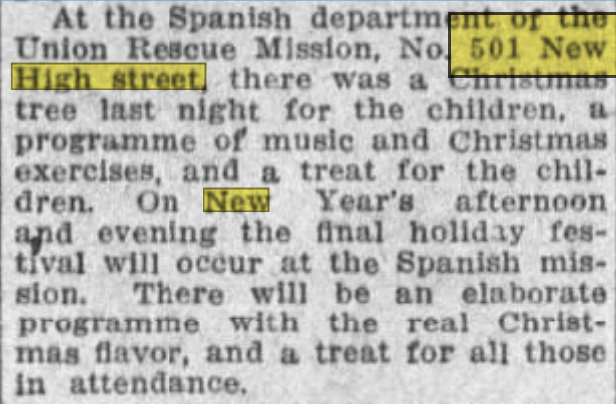

LA's original Chinatown was emptied and razed to build Union Station. Where did all the Chinese Angelenos go?

The area now known as Chinatown was full of French Angelenos first. Wikipedia incorrectly states that it was originally Little Italy. It's true that Italians did live in the neighborhood, but the French arrived before the first Italians did, and made up a larger percentage of the population. Why did the demographics change?

No deed restrictions to keep out Chinese residents - or, for that matter, Italian residents. (Catholics of all origins occasionally clashed with Chinese Angelenos over religious differences, but the French community welcomed newcomers from Italy. Case in point: two of the French Benevolent Society's founding members were Italian. And the French Hospital did accept Chinese patients at a time when most hospitals wouldn't.)

LA's Jewish community was largely based in Boyle Heights for many years. Guess who else lived in Boyle Heights back in the day? There were Anglos, sure, but there were also Basque farmers. In fact,

Simon Gless' big Victorian house was used as office space for the Hebrew Shelter Home and Asylum for many years (the last time I checked, it was a boarding house for mariachi musicians).

Once again - no deed restrictions. (Why does Los Angeles County have so many Jewish residents? Because Jews have, historically, been more welcome in Los Angeles than in many other places. Los Angeles was a tiny frontier town when the first Jewish residents arrived, and in the Old West - where people had to work together to stay alive - how you treated people mattered more than what house of worship you attended.)

I haven't found anything on whether Pellissier Square ever had deed restrictions or not, but there's a reason Korean Angelenos originally clustered in Bunker Hill. Prudent Beaudry - who developed for everyone - developed Bunker Hill. Like Angelino Heights,

Bunker Hill was unrestricted.

How did Frenchtown cease to be called Frenchtown?

Simple. As the city expanded westward, and as many French Angelenos moved west or left the city entirely in search of land for grazing livestock/farming/growing grapes, people who weren't welcome in other areas moved to the historically French - and historically unrestricted - neighborhoods.

If you were in the same situation, wouldn't you?