But that changed when two brothers arrived - separately - from the French region of Haute-Garonne in the 1850s.

Louis Sentous, born in 1840**, came to California in 1853 to do some gold prospecting (there were a few smaller gold rushes after the big one) before moving to LA. Before long, he was raising cattle, selling dairy products, and running a butcher shop.

Louis married Bernath "Bernadette" Lasere, who was also from Haut-Garonne, in 1871 or 1872 (it isn't clear which date is correct). Their son Julius John was born in December of that year, followed by Marie-Louise (1873), Narcisse (February 1880), and Adele (December 1880).

I should note that some sources cite Louis arriving in 1871. However, there is plenty of evidence he was in California in 1853 and for years after. I surmise Louis traveled home to France to get married (it's possible he needed to find a bride; there weren't many single women in LA back then) and the census taker may have mistakenly put down 1871 as the year of arrival for both Louis and Bernadette.

The Sentous Brothers Ranch was near modern-day Jefferson and Western and may have been established as early as 1860. Their cattle are long gone; today, two fried-chicken chains, a bus stop, and a car wash can be found at Jefferson and Western.

In 1874, Louis moved his family to a farm in Calabasas. They moved back in 1877 (given that Miguel Leonis controlled much of Calabasas in the 1870s, who can blame them?). Louis owned the farm until he sold it in 1884, retiring to his home on Olive Street opposite what is now Pershing Square (the exact address isn't clear, but he would most likely have lived next to Remi Nadeau).

The 1883 city directory lists the L. Sentous and Co. butcher shop at the corner of Aliso Street and Los Angeles Street. However, the business prospered well enough that Louis set up the first meatpacking house in Los Angeles. The Sentous meatpacking plant (close to modern-day Culver City) was large enough that it was a stop on the Pacific Electric Railway's fabled Balloon Route, and the plant was the subject of at least one postcard image (more info here). Sentous Station was demolished long ago, but its location is still used as the La Cienega/Jefferson stop on the Expo Line.

Louis Sentous Sr. died in 1911.

Jean Guillaume Sentous, born in 1836, was a dairy farmer and wool rancher. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1854, 1856, or 1860 (sources disagree) after a stint in mining up in Calaveras County.

In 1867, Jean married Maria Theodora Casanova, born in Costa Rica to Spanish parents, at the Plaza Church. They had eight children - Narcisse (born 1868), Louis Jr. (born 1869), Francois (born 1871), Camille (born 1873), Heloise (born 1873*), Louisa (born 1876), Emely (sometimes written as Emila; born 1878), and Adele (born 1880).

There were two more Sentous brothers - Alphonse, born in 1850, and Pierre-Marie, whose birth year seems to be lost to history. Alphonse likely arrived later (there is no record of him in California until 1873), and Pierre remained in France. Little else seems to be known about either of them.

Like many other early residents who were able to buy land before the real estate boom of the 1880s, the Sentous brothers had considerable holdings, including a building block. The Sentous Block at 617 N. Main Street, built by Louis in 1886, housed both apartments and shops. In fact, former governor Pio Pico spent his last few years in an apartment in the Sentous Block (needless to say, he'd had some money troubles).

Jean Sentous established a dairy farm in 1856, on land bordered by Main, Washington, Grand, and 21st Streets. The land exchanged hands a few times and eventually became Chutes Park, one of LA's first amusement parks, in 1900 (sadly, in typical fashion, LAist neglected to mention the French guy who owned the land before that hotelier did).

There was a Sentous Tract, divided by Jean in 1861 and bordered by Pico, Georgia, Eleventh, and Sentous Street. The Sentous Street School was built at 1205 W. Pico in 1912, and later renamed Sentous Junior High School (the campus doubled as a night school).

Although Jean preferred family life to public life, he served as President of the French Benevolent Society for many years.

Jean died in 1903 at age 67 in his home at 834 West 16th Street (the 800 block of West 16th Street no longer exists). His funeral was held at St. Vincent's and he was buried at Calvary Cemetery. The funeral procession was the largest Los Angeles had ever seen (at least as of 2007, when this fact was cited in historian Helene Demeestre's Pioneers and Entrepreneurs).

Jean's son Louis Sentous Jr., who was just as popular as his gregarious father and uncle, was educated in Los Angeles public schools and St. Vincent's College before spending five years in France, attending the Seminary of Polignan and the Government College in St. Gaudens. Upon returning, he re-enrolled in St. Vincent's (which we know today as Loyola Marymount University) and graduated. Louis Jr. married Louise Amestoy, also from a notable French family (I will cover the Amestoys at a later date) in 1895.

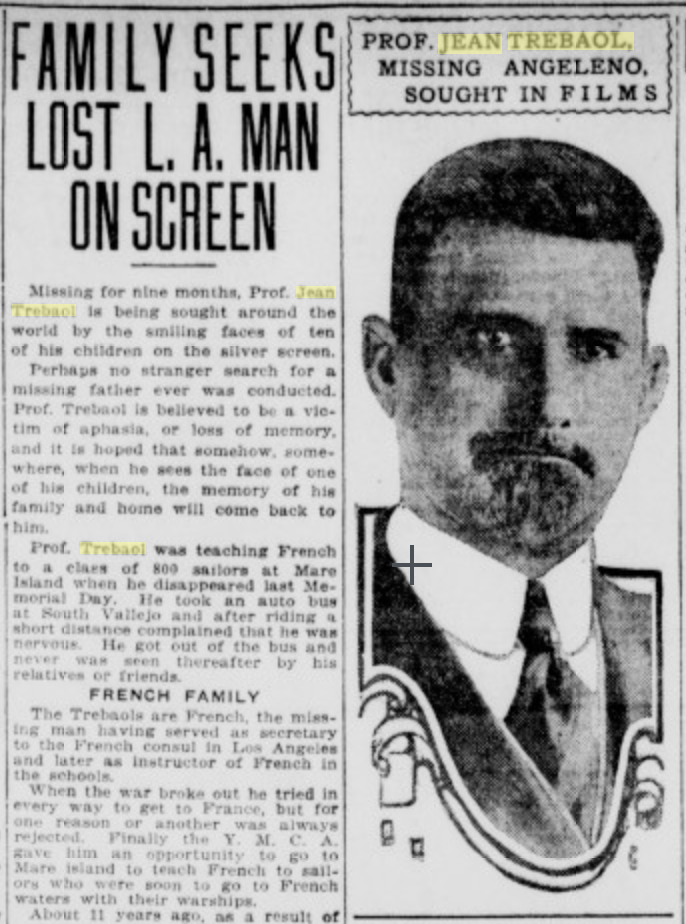

Louis Jr. was President of the Franco American Baking Company for some time, developed real estate with his brother Camille, and served as LA's French consul for many years. (Demeestre mistakenly - but understandably - lists Louis Jr. as Louis' son. Birth records and Jean's newspaper obituary make it clear that Louis Jr. was in fact Jean's son.) Louis Sentous Jr. held several offices in the French Benevolent Society and was the Society's President for thirteen years, during which time the Society's membership more than doubled. In 1912, the French government made him a decorated officer of the French Academy for his years of service.

The Sentous family wasn't immune to trouble. In 1907, Louis Jr. and Camille were threatened by a deranged laborer, Quentin Prima, who demanded their assistance in courting their wealthy widowed aunt. Fortunately, Prima was promptly arrested.

Of Jean's other children, we know that Frank became an engineer, Narcisse bounced back home after a divorce, Adele and Louisa got married but Heloise did not (in the grand tradition of French women living very long lives, Adele died at age 90 in 1971), and poor Emely died when she was only 15.

The Sentous Block - incredibly - managed to survive until 1957. When it was finally slated for demolition (to build - what else? - another parking lot), Christine Sterling, the "Mother of Olvera Street", was so heartbroken that she put on mourning attire and hung a huge black wreath on the building's center door (as you can see in the picture below).

Mrs. Sterling lamented "I had always hoped that the Sentous Building would be included in the city, county and state's plans to restore the Plaza area. But it looks like another part of our past is going to be carried away in a truck." (Emphasis mine. If Mrs. Sterling could see modern-day LA, she would probably be inconsolable.)

Sentous Junior High School closed in 1932, after only 20 years of teaching children (and adults). As the city expanded westward in the 1930s, more and more families moved out of downtown. The school was not demolished until 1969.

The rest of the Sentous Tract was cleared out and demolished around the same time to build (drumroll please...) a parking facility for the Convention Center. The Staples Center and LA Live came later. (On a personal note, I was harassed at LA Live by a racist scumbag who took issue with my beret and my ethnicity. I felt threatened enough that I didn't stick around to say hi to second opening band The Dollyrots, even though I love them - I bolted for the parking garage and beat it straight back to my apartment across town. That was in 2010 and I still remember it like it was yesterday. I'm never, EVER going to a Screeching Weasel show again.)

As for Sentous Street, it was renamed LA Live Way.

A few of LA's streets still bear the family's name. City of Industry boasts both a Sentous Avenue and a Sentous Street, and West Covina has its own Sentous Avenue. (Given later freeway construction and the proximity of the two Sentous Avenues, they may at one time have been portions of one continuous street.)

*Camille and Heloise were, according to existing records, born just six weeks apart. It isn't clear if this is the result of a clerical error or unlikely medical circumstances, or if either child could have been adopted.

**Multiple sources say Louis was born in 1848, but others, including his grave marker, indicate a birth year of 1840. Since young children don't normally go to a faraway country alone at age five, 1840 seems far more likely. Emigrating alone as a younger teenager would not have been that unusual for the 19th century (case in point: one of my great-grandfathers emigrated alone at age 14, lived in boarding houses until he got married, and - if his birth family was even still alive - never saw any of them again).