Modern-day Los Angeles has a number of French-language private schools. The very first is long defunct; it was founded long ago by Teresa (sometimes written as Therese or Theresa) Bry Henriot.

Teresa Bry is said to have cut her teeth teaching in Geneva, Switzerland before departing for faraway Los Angeles. Besides French, she spoke German, English, and Spanish well enough to teach in all four of those languages.

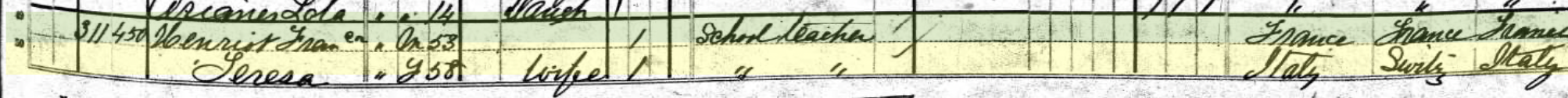

Teresa Bry was born in 1822 - not in Switzerland, as some sources claim, but in Italy (census records bear me out on that) to an Italian mother and a Swiss father. She has been described as "highly educated", but her educational background has proven elusive, along with many other details of her life.

|

| 1880 census records of the Henriots |

In any case, Teresa Bry moved to Los Angeles in 1854 and married French-born gardener François Henriot four years later. She was 32, he was 27.

I've mentioned previously that early LA's Italian community was very small and there were even fewer Swiss Angelenos. In the 1850s, the few Italians and French-speaking Swiss in LA were welcomed by, and often associated with, the much larger French population. Intermarriage, in and of itself, would not have been surprising.

Harris Newmark knew the Henriots and described their marriage thusly:

"This matrimonial transaction, on account of the unequal social stations of the respective parties, caused some little flurry: in contrast to 226her own beauty and ladylike accomplishments, François's manners were unrefined, his stature short and squatty, while his full beard (although it inspired respect, if not a certain feeling of awe, when he came to exercise authority in the school) was scraggy and unkempt."

Opposites attract, or so they say.

Madame Henriot would establish her French School (later the Henriot School) on San Pedro Street at First Street, about a nine-minute walk from the core of the French Colony. Directory listings tend to place the school on the western corner of the intersection. Today, it's firmly within Little Tokyo. Newspaper advertisements suggest that the school opened its doors February 2, 1874.

In those early days the school could very well have been run out of their house - the 1875 city directory lists "Henreot Mrs T., teacher French School, San Pedro nr First" and "Henreot F, res San Pedro nr First". Several pages later, the directory lists "French School - Mrs. T. Henreot, Teacher. Average number of pupils, 28. School, San Pedro nr First." (Yes, the directory misspelled every instance of Henriot.)

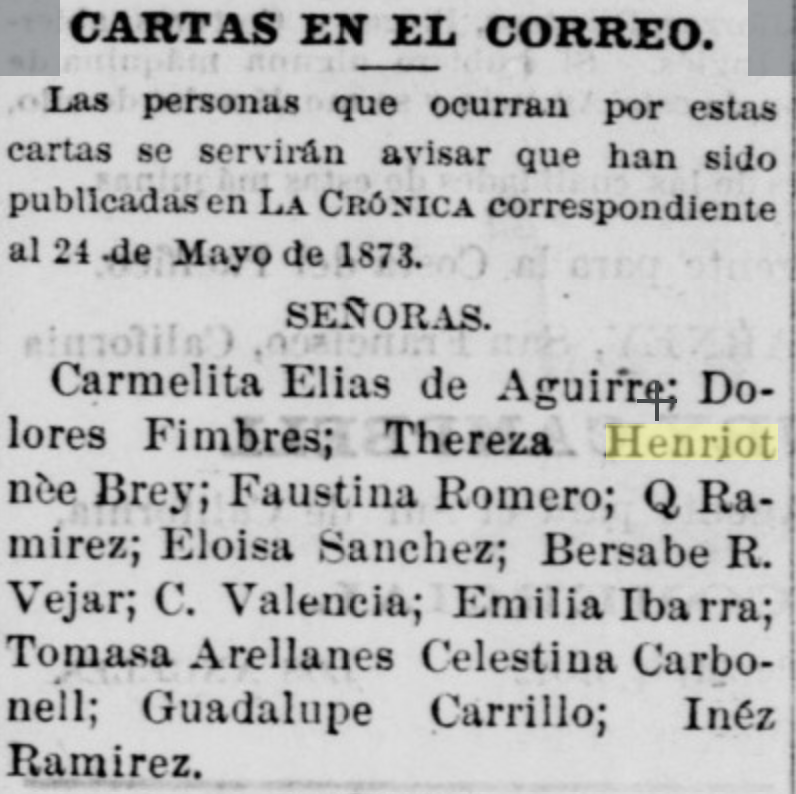

Lessons were conducted in French, with optional Spanish and German classes. The multilingual Henriots both spoke Spanish well enough to have letters published in La Crónica. In fact, La Crónica favorably described Mme. Henriot (in part and translated from Spanish):

"We know that said lady, known to everyone in our county and City of Los Angeles, is one of the most talented and appreciable teachers in California, which is why she is justly appreciated by our Hispanic-American population."

|

| Ad for the Henriot School in La Crónica, 1874 |

|

| The Henriots, Teresa more than François, had several letters published in La Crónica. |

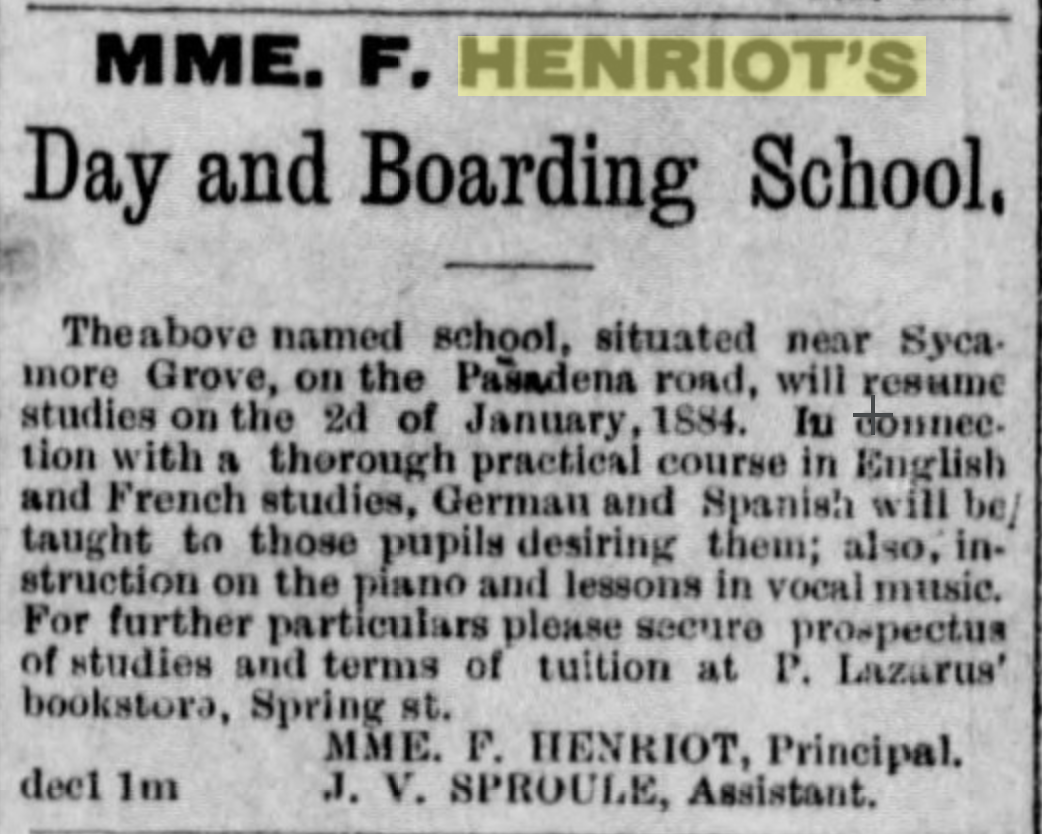

It isn't clear when François Henriot gave up gardening to become a teacher, but the Henriots eventually taught and ran the school together. In time, demand for French-language education grew enough that the school on San Pedro Street was insufficient, and a combination day and boarding school had to be established somewhere with more space.

So where did Mme. Henriot's French school go when it left downtown?

I found references to the school relocating to Pasadena, or close to it, at an unknown date. Yet, I could find no record of the Henriot School in Pasadena. To its great credit, Pasadena seldom erases its own history. Hmm.

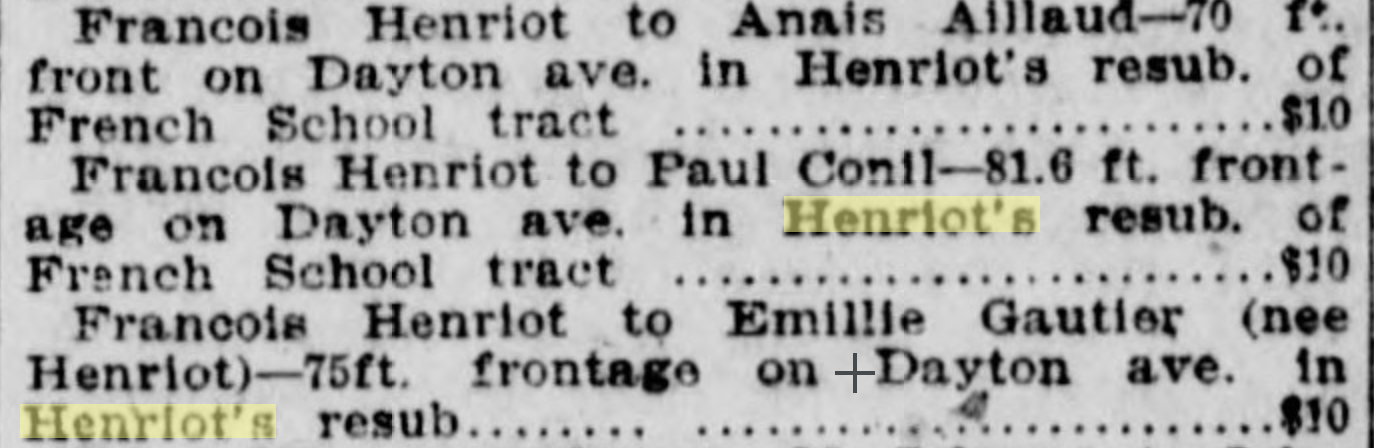

While searching for any available information on the Henriots, I found a reference to a Henriot Avenue in a list of tax-delinquent properties.

|

| Henriot Avenue referenced in a delinquent tax list |

|

| Newspaper ad referencing the Henriot School "near Sycamore Grove, on the Pasadena road", 1884 |

|

| Newspaper announcement mentioning the school was "at Arroyo Seco", 1886 |

From these newspaper clippings, we can conclude three things: that there was a street named for the Henriots, that the school was "near Sycamore Grove, on the Pasadena road" (hence the misbelief that it was ever in Pasadena), and that the school was also "at Arroyo Seco".

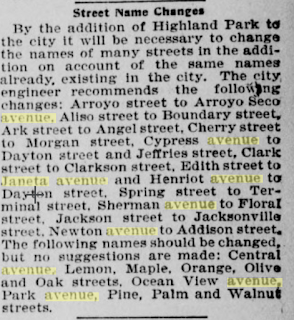

Street names can be a very telling indicator of who lived in an area long ago. But where was Henriot Avenue?

|

| Street name changes, Los Angeles Herald, 1896 |

|

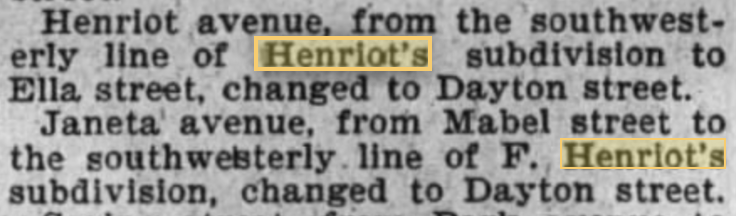

| Street name change announcement referencing "Henriot's subdivision", 1896 |

So Henriot Avenue became Dayton Street. And it got a name change when Los Angeles annexed Highland Park.

A quick search pulled up Dayton Avenue in San Pedro (nope), Pomona (nope), and in Pasadena, but not near the Arroyo Seco or "the Pasadena road" (nope). So the street must have had another name change.

According to genealogist Steve Morse, Dayton Avenue became North Figueroa Street in Cypress Park.

Sanborn maps from 1906 bear out Morse on the name change. They also show a large wooded area nearby (now gone and filled in).

So, Henriot Avenue became North Figueroa Street. If you're starting out downtown, Cypress Park is on the way to Highland Park. And of course North Figueroa Street extends all the way through Highland Park until it turns into Scholl Canyon Road in Eagle Rock.

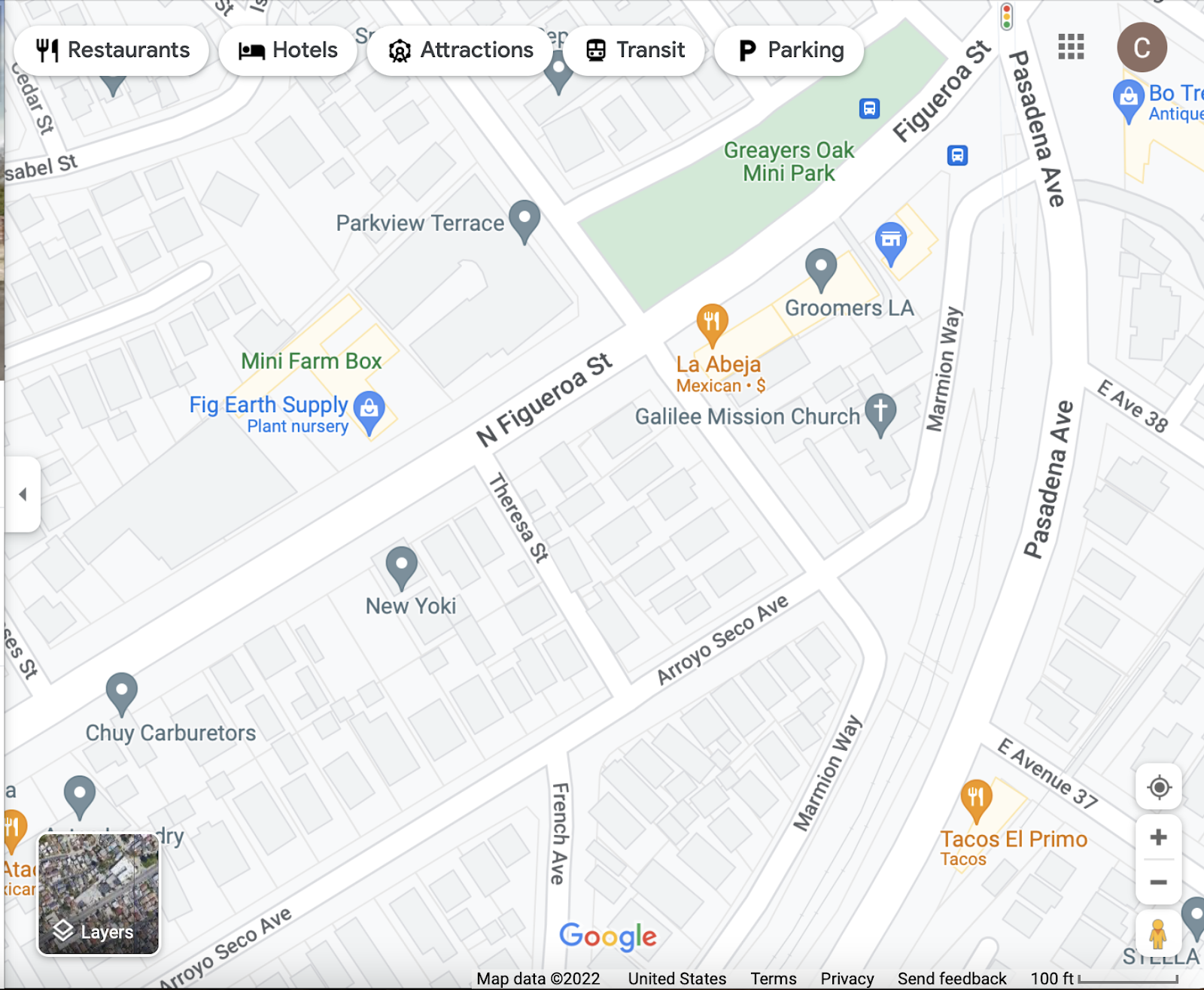

The above Google Maps screenshot shows North Figueroa Street, aka Henriot Avenue, intersecting with Pasadena Avenue. Very close by are Theresa Street, probably named for Mme. Henriot, and French Avenue.

I have been scouring the internet in vain for a map showing Cypress Park in the 1880s, when the school was open. I have yet to find one. Even Sanborn maps let me down this time - the earliest one I could find is from 1906, after the campus was redeveloped.

Still, given the geographical evidence, I feel comfortable saying the Henriot School was located somewhere along Pasadena Avenue, near North Figueroa. I will continue to look for 1880s maps of the area to pinpoint a more precise location.

|

| In a likely sign of the times (more English speakers were flooding into LA), the Henriot School eventually switched to conducting classes in English, with optional French and Spanish courses. |

I found one reference to Mme. Henriot passing away in 1888, with no further details. Another source suggests it was 1898, which tracks with M. Henriot passing away in 1903 (in the French Hospital). Harris Newmark stated that they died five years apart.

There is a mysterious footnote to all of this: one of my books states that an oil portrait of Mme. Henriot was displayed in the County Museum (now the Natural History Museum) at the time of publication. Some time ago I reached out to the Museum asking about the portrait, as I have never seen it displayed. The book didn't reference the artist, and the portrait isn't in the Seaver Center's database. The collections manager mentioned that it would be difficult to trace without knowing the artist's name, and suggested it may have been part of a temporary exhibition by the California Art Club. However, this doesn't seem likely, since the reference is from decades after Mme. Henriot's death.

Does anyone out there have any idea what happened to the portrait, or do I have to go on a mission to find it like Indiana Jones? After all...it belongs in a museum.