Prudent Beaudry was wealthy and successful. But he, personally, didn't spend all that much on himself.

He did take a vacation once, in 1855. He went to Montreal to visit his brother Jean-Louis (

who later became Montreal's Mayor) before continuing on to Paris to see the Exposition Universelle and visit world-famous oculist Dr. Jules Sichel in hopes of improving his poor eyesight.

But, for the most part, Beaudry seems to have funneled his earnings right back into his varied business ventures and into improving his adopted city. For such a successful man, he lived relatively frugally.

Modern-day Angelenos might expect Beaudry - a successful developer, business owner, and two-term Mayor - to live in a beautiful, spacious house in an upscale neighborhood.

He didn't.

Prudent Beaudry's house on New High Street

|

| | Side view of Prudent Beaudry's house |

|

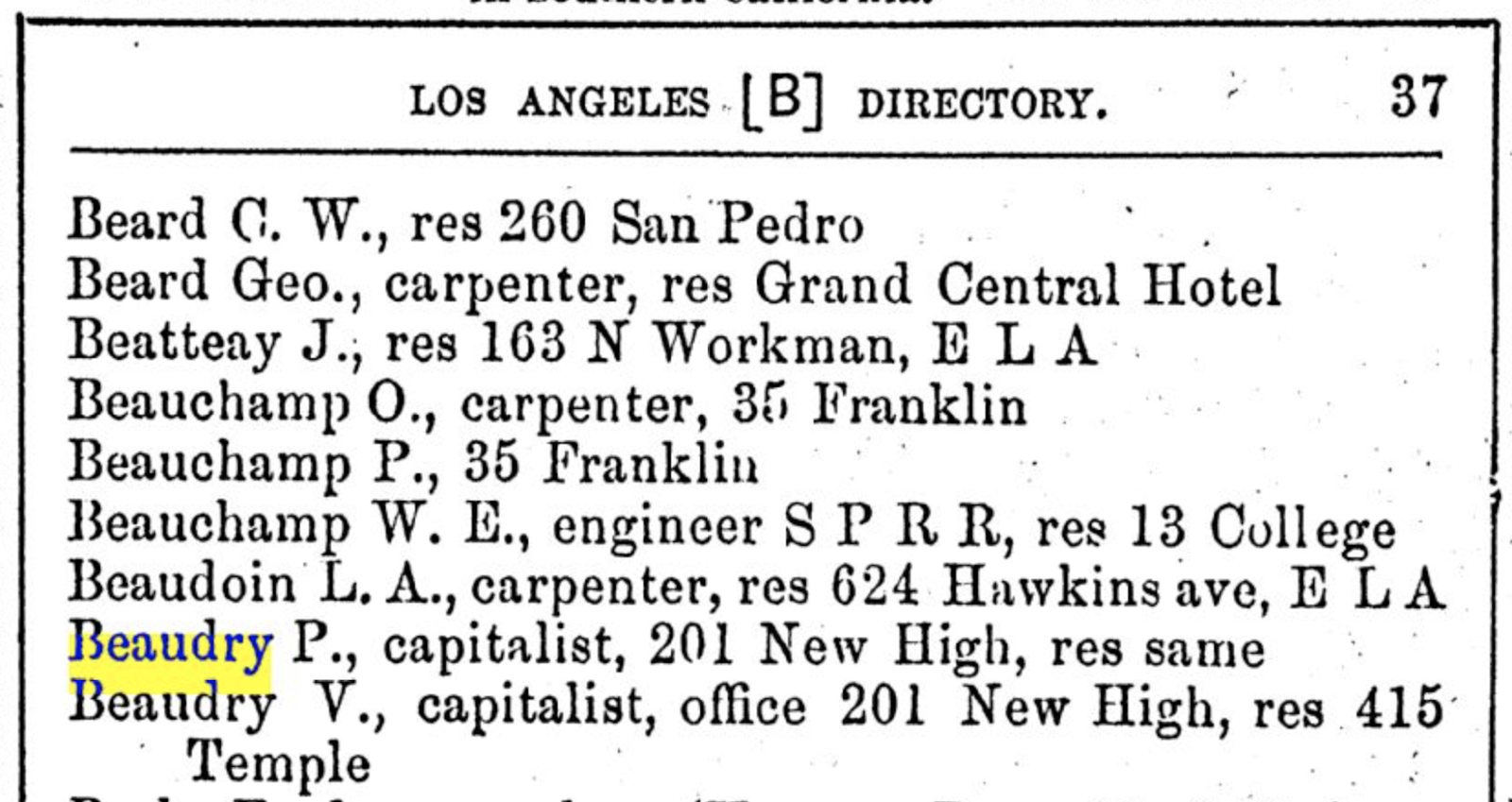

Prudent Beaudry lived alone in a fairly narrow three-story tenement-style house close to the Plaza - not even on Bunker Hill, which he developed. And the house doubled as the Beaudry brothers' real estate office and the office of the Temple Street Cable Railway (which they helped develop) for a time. Victor lived on Temple Street with his wife and children.

|

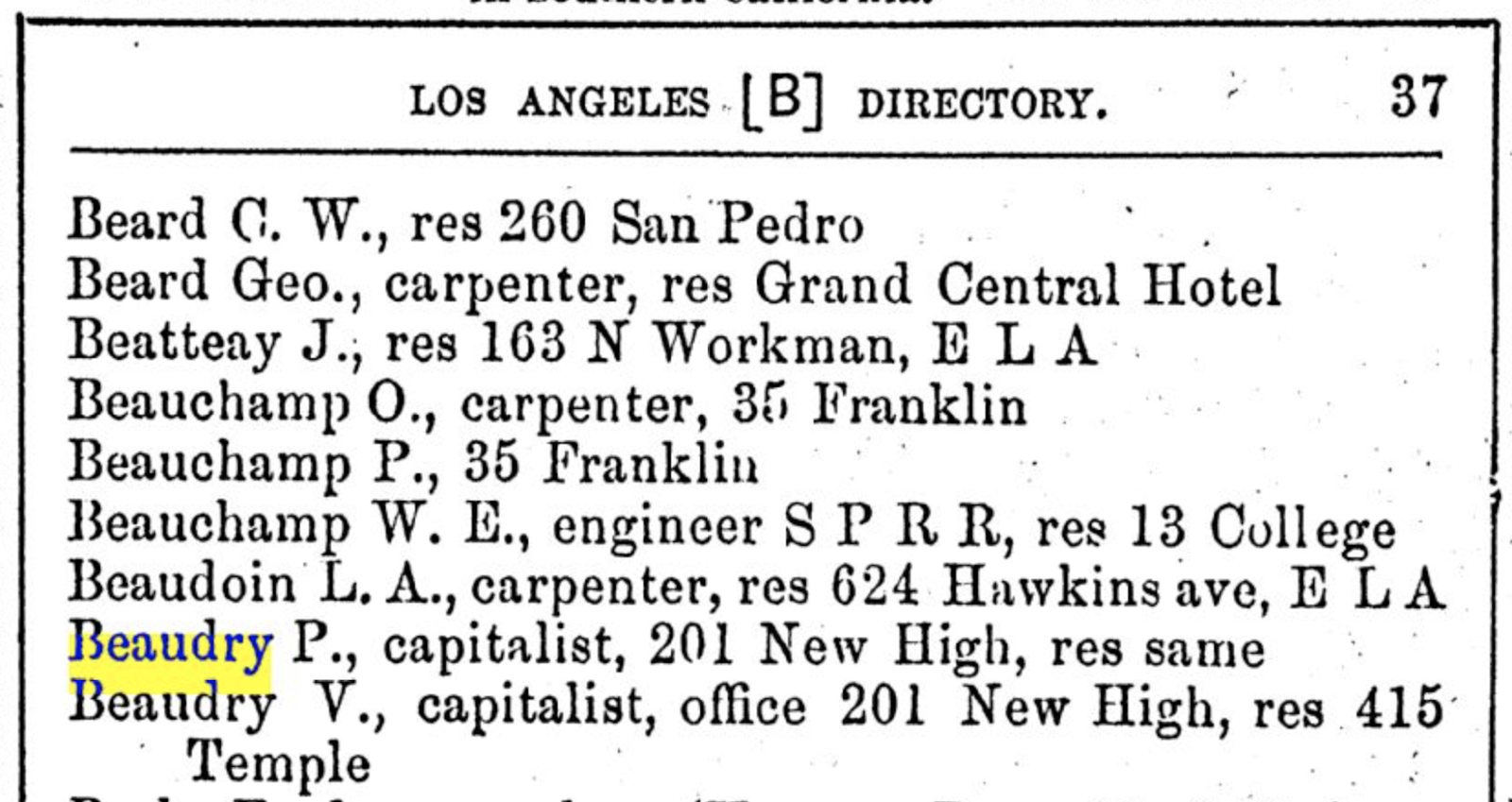

| 1883-1884 City Directory listing for Beaudry's house/office on New High Street |

The house was initially assigned the address of 81 New High Street. By 1884, the street numbering had changed, making the address 201 New High Street. The address changed again later, to 501 New High Street.

Prudent Beaudry passed away in 1893, by which time he had moved out of the little house on New High Street. New owners were renting out rooms.

|

| 1892 ad for rooms to let in Beaudry's former home |

A Mrs. Sallie Bailey was living in the house in 1893, and filed a criminal complaint against a Mr. George White for attacking her with a pistol.

A few months after Beaudry's death, the house factored into a scammer's lurid plot.

San Francisco con artist J. Milton Haley arrived in Los Angeles and soon heard of three sex workers who wanted to open their own brothel. (Prostitution was somewhat tolerated as long as it was confined to the area now occupied by Union Station, Father Serra Park, and the El Pueblo parking lot.) Haley posed as the Chief of Police's confidential clerk and offered to rent out 501 New High Street for them.

By this time, the house was jointly owned by a Mr. Nolan and a Mr. Smith. Haley got the house's keys from them on the pretense of looking over the place, then forged a receipt. Unfortunately for Haley, the sex workers did their due diligence by going to police headquarters and asking questions.

Thirteen days after arriving in Los Angeles, the San Francisco scammer was arraigned for forgery.

A 1900 news blurb indicates that a fire at the building necessitated a permit for $130 worth of repairs.

|

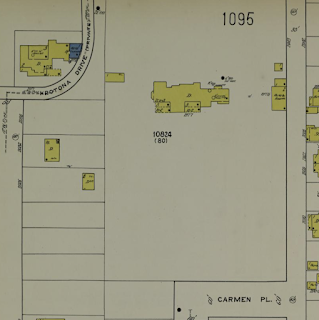

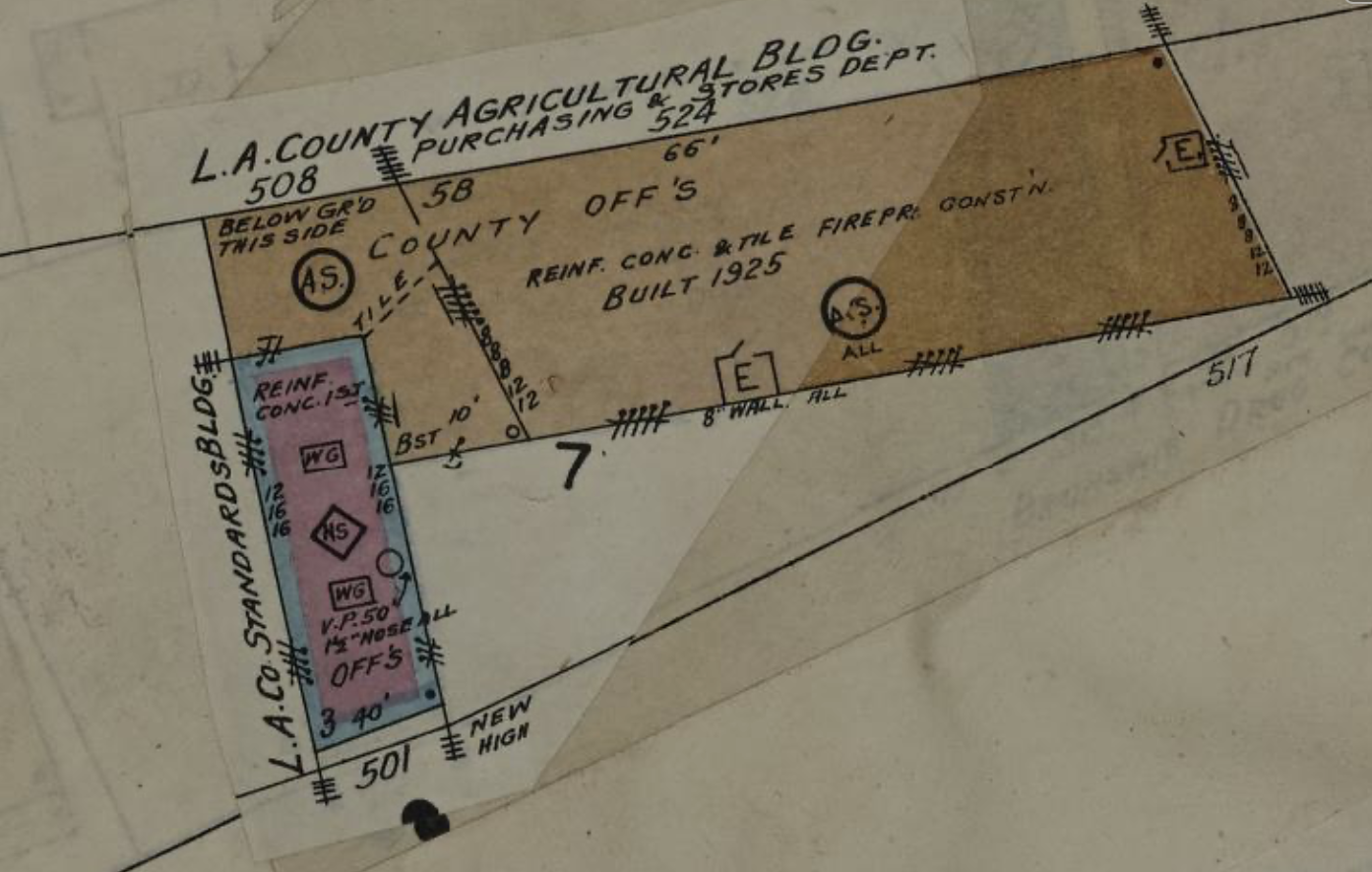

Detail of Beaudry's former home at 501 New High Street in 1906 Sanborn Map.

Do note that it is now identified as a paint shop, with a dwelling on the second and third floors. |

|

501 New High Street's former location in context with other Plaza-area buildings. It would have been across New High Street from the back of the Brunswig Building (still F.W. Braun & Co. at this point).

| | 1903 ad for Craig & Burrows' painting and wallpaper hanging business, based in the Beaudry house |

|

I surmise that the ground-level office space and the upstairs living quarters may have been either rented out separately or one tenant sublet the unused space to another. Newspaper ads continue to place Craig & Burrows' paint and wallpaper business in the house, along with co-owner George Craig (Frank Burrows lived at 501 1/2). But, a 1906 news blurb notes that Mahogany Hall, a notorious brothel, was

also located at 501 New High Street (presumably upstairs). Mahogany Hall was dubbed "Suicide Hall" by the twenty-five Black and mixed-race women trafficked inside, and was considered one of the absolute worst places in Los Angeles. (I should note that at least one 1906 account places Mahogany Hall at

515 New High Street; however, number 515 doesn't exist on the 1906 Sanborn map.)

Ironically, another article about Mahogany Hall stated that the courthouse had used 501 New High Street as office space at one point.

By 1907, the house was so dilapidated and filthy that it was being eyed for condemnation and demolition along with several older adobe houses down New High Street. However, the city directory continued to list Craig & Burrows' paint shop at the address. I surmise the owners made some badly needed repairs after the brothel's closure, since the directory lists a variety of renters, including Spring Street dentist Dr. Tagaki, living in the house beginning in 1908.

A 1915 news blurb states the building was leased to E.F. Potter for a branch of the Bible Institute. That arrangement can't have lasted long, since a year later it was housing the Sonora Union Gospel Mission, a Spanish-language branch of the Union Rescue Mission (yes, this is the same Union Rescue Mission active today - it dates to 1891).

|

1916 blurb placing the Union Rescue Mission's Spanish-language branch at 501 New High Street

|

The mission seems to have moved out by 1923, since the city directory places restauranteur Florentino Jimenez at 501 New High Street, followed by Refugio Guerrero in 1927. Mrs. Marie Jimenez appears in listings in 1928.

The city directory failed to identify the restaurant on the premises, but the LA Times didn't. Lee Shippey's column mentioned it twice:

|

Excerpt from "Lee Side O' LA" mentioning Moctezuma Restaurant

|

Shippey, detailing Arthur Millier's 1928 exhibition of etchings at what is now the Natural History Museum, noted "Many of us have passed it a hundred times without noticing that there is a great deal of artistic beauty in the rather dingy building on New High Street which shelters the Moctezuma Restaurant." (Millier's etchings were all of California scenes, and more than half were of scenes in the Plaza area. Some of them can be found in world-class art museums. Please let me know if the etching of Beaudry's house ever turns up.)

Several paragraphs later, Shippey added "And all are of things which soon must pass away before the onrush of progress. Within a few years most of the things pictured in this collection will be only memories to the people who possess such pictures as Millier's - and not even memories to most of us." (City Hall was dedicated nearly nine weeks later and the plans for Union Station were under way. The original plan was to wipe out the entire Plaza, but that's an even longer story and the main character is Christine Sterling.)

How do we know Moctezuma Restaurant was located at 501 New High Street?

The LA Public Library has photographic proof (although I am not sure the 1910 date is accurate).

Three months later, Shippey's column revisited 501 New High Street. In part:

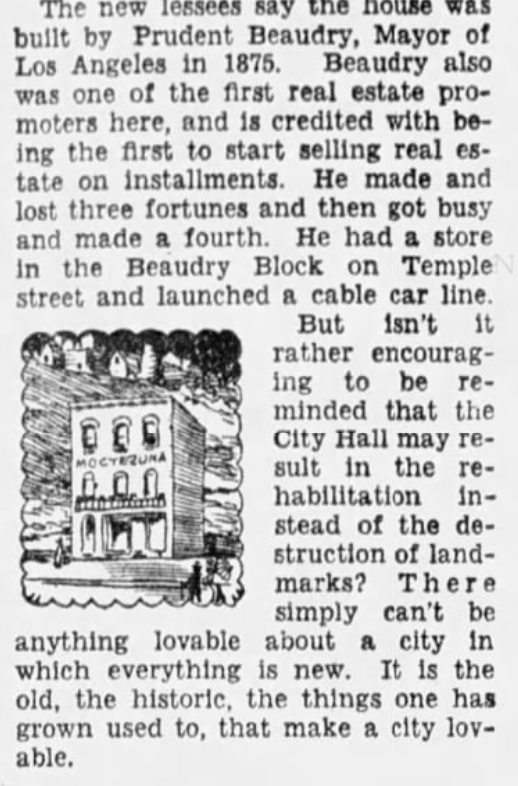

Some months ago we were walking with Arthur Millier, the artist, when he stopped before the three-story house on New High Street which bore the name of the Moctezuma Restaurant, and began to sketch.

"There is something really beautiful, really interesting," he exclaimed. "There is some real art on that simple, friendly house front."

We wondered what the history of the place was, but no one we asked then knew anything about it.

Mexicans who knew nothing of the history of the place were living there then, and it had not been used as a restaurant for a long time. But the interior of the house was as interesting as the exterior, full of quaintness and beauty in a setting of brick and adobe. This was discovered recently by some folks who wish to start a tea-room close to the City Hall, and now the old place is being refurnished as an early-day Los Angeles home.

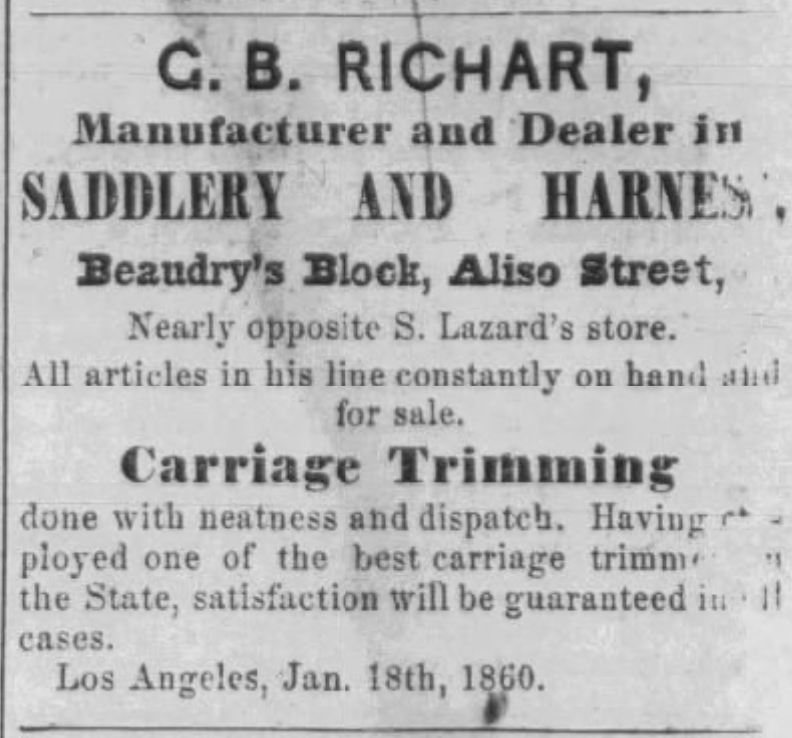

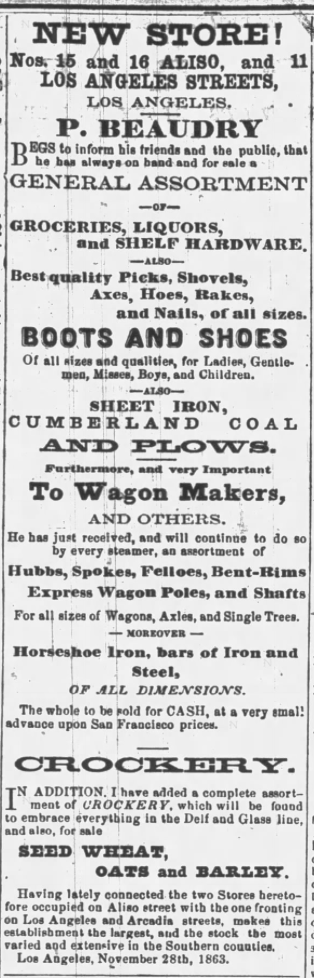

The new lessees say the house was built by Prudent Beaudry, Mayor of Los Angeles in 1875. Beaudry also was one of the first real estate promoters here, and is credited with being the first to start selling real estate on installments. He made and lost three fortunes and then got busy and made a fourth. He had a store in the Beaudry Block on Temple Street and launched a cable car line. [Shippey got the street wrong, per my last entry.]

But isn't it rather encouraging to be reminded that the City Hall may result in the rehabilitation instead of the destruction of landmarks? There simply can't be anything lovable about a city in which everything is new. It is the old, the historic, the things one has grown used to, that make a city lovable.

(Emphasis mine.)

|

| Snippet from Shippey column referencing Prudent Beaudry's house |

As you can see from the clipping, the Moctezuma Restaurant was also a clean match for Beaudry's narrow three-story house.

Unfortunately, Shippey's first prediction ultimately proved correct. Water and Power states that Beaudry's humble house was torn down in 1931. (In between, it housed La Bombilia Restaurant in 1930.)

|

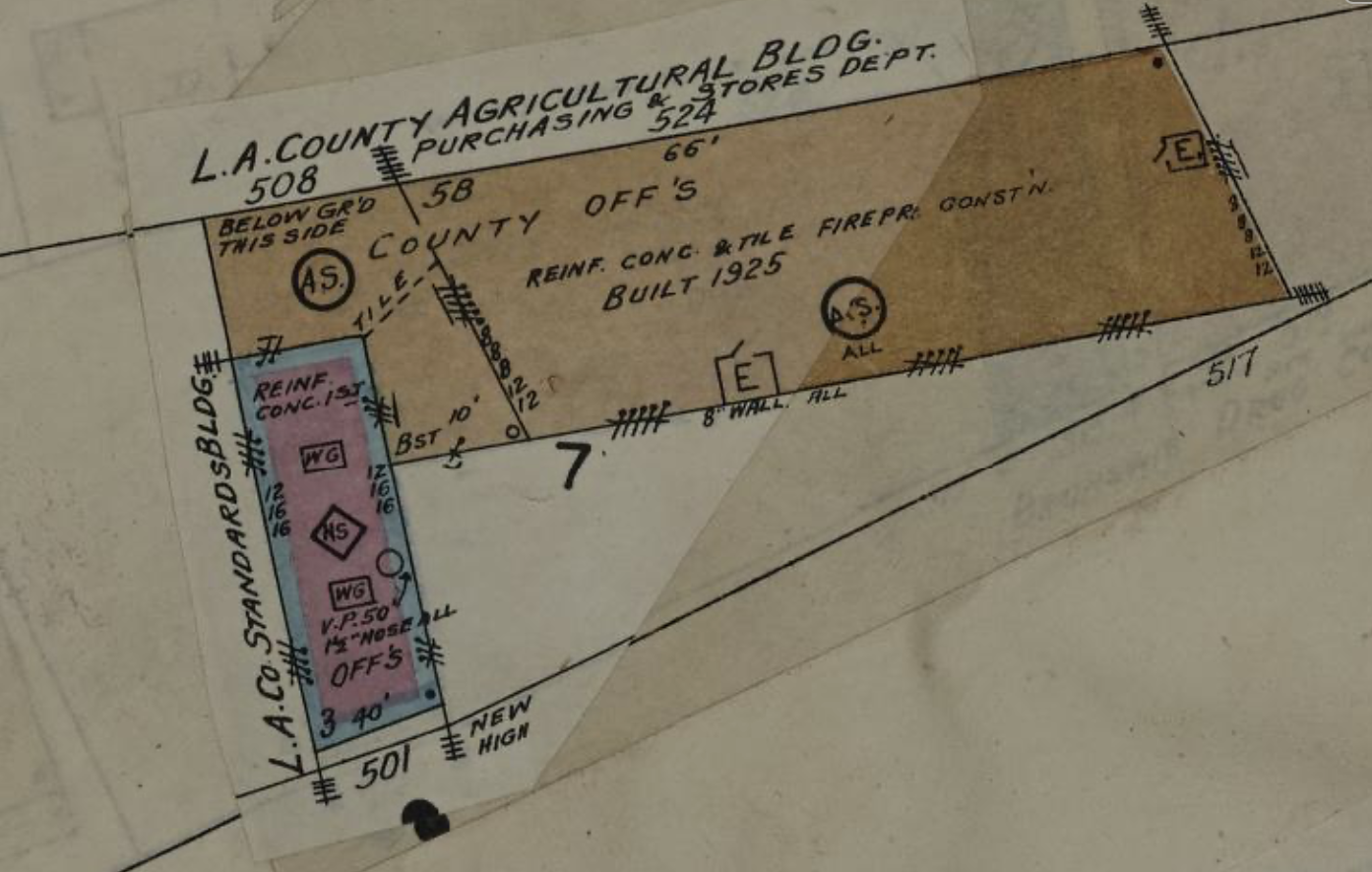

Detail of 501 New High Street from 1906-1950 Sanborn map

|

The above map snippet shows the County Bureau of Weights and Measures at 501 N. Main. However, the building is six feet wider and much deeper than Beaudry's humble house - plus the first floor is made of reinforced concrete. I believe this was a newer building added later. Strangely, like its predecessor, it served as emergency courthouse space in 1947. After that, it was a sheriff's department laboratory (which later moved across the street to the Garnier Block).

The 500 block of New High Street no longer exists, of course. Like a depressingly high number of other things in Los Angeles, it disappeared under a parking lot many years ago (most likely in the 1950s when the freeway wiped out much of what surrounded the Plaza).

Beaudry's house survived Beaudry's death, the decline of the Plaza area, generations of renters, doubling as a squalid brothel with a violent reputation, and nearly being torn down twice (1907 and 1928). It was undergoing restoration. It was going to survive after all...and then we lost it.