Dear Readers: the French Hospital is in danger of being torn down by a San Francisco developer.

I have sent the following letter to the Office of Historic Resources and to the Cultural Heritage Commission.

Should you wish to do the same, here is the Office of Historic Resources' directory and the Cultural Heritage Commission's email address is chc@lacity.org.

Dear Principal City Planner Bernstein et. al.,

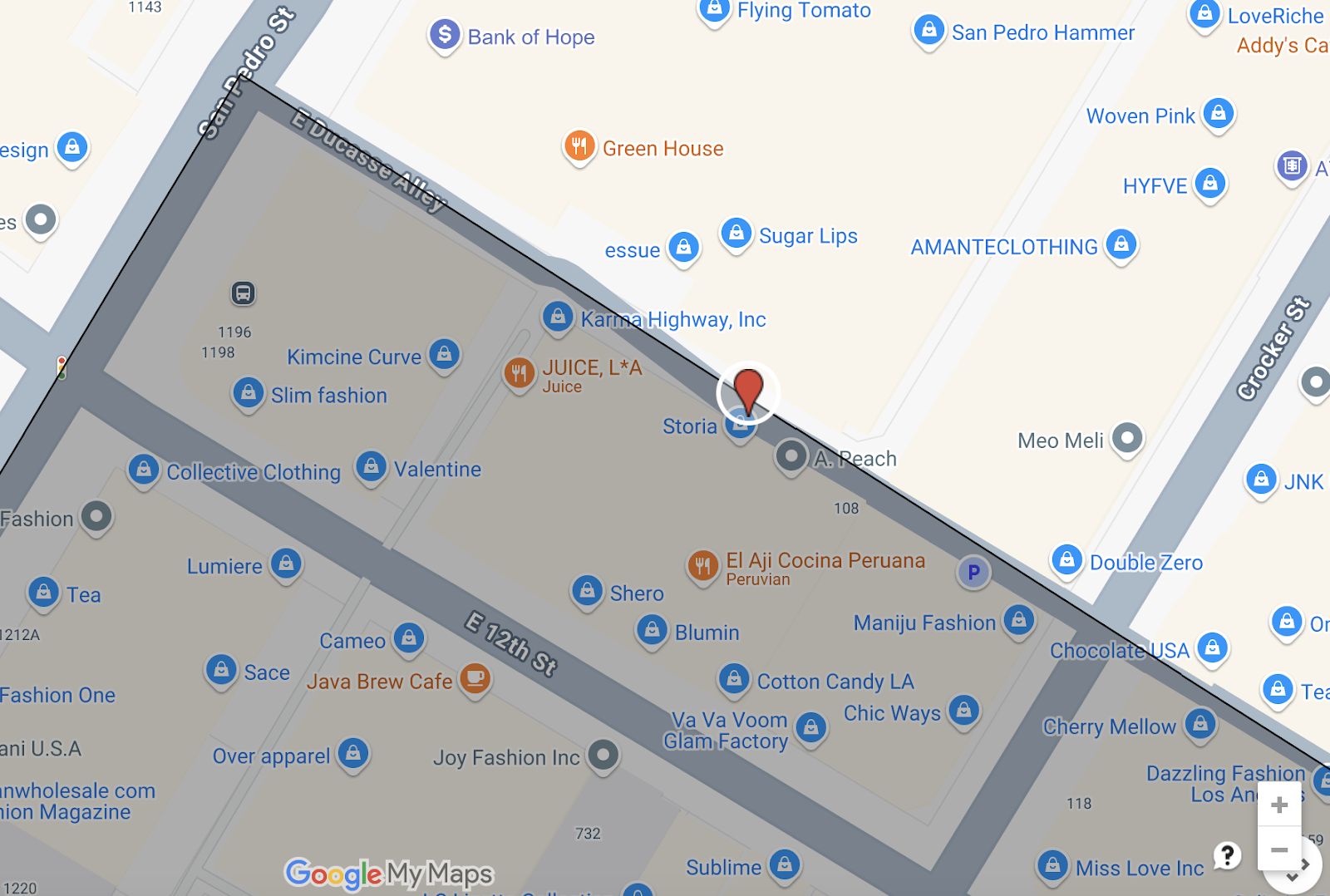

I have spent the past 12 years documenting and mapping Los Angeles’ once-thriving French and Francophone community (about 14 percent of the city’s 1860 population alone per census data), which was based in what is now Little Tokyo/the Arts District. 531 W. College Street was the French Hospital from 1870 to 1989.

French and Italian Angelenos laid the cornerstone for the original adobe hospital building in 1869. The only other hospital in Los Angeles at the time was St. Vincent’s, making the French Hospital the first non-sectarian hospital in the city. The hospital was rebuilt and modernized in 1915, with an expansion added in 1926. An old Chinatown legend has it that part of the original adobe hospital building is encased within the 1915 hospital’s walls.

I would like to invite you to examine Sanborn fire insurance maps from before and after the 1915 rebuild. The two hospitals have similarities to their footprints, and it’s certainly possible that a portion of the 1869 hospital may indeed remain. Further, who knows what may be buried underneath the 1915-1926 building? At bare minimum, an archeological survey needs to be conducted.

For over a decade, I have spoken for the lost French Colony because no one else was representing it accurately. I will speak for this hospital. It is indeed a historic building, and it matters to generations of French Angelenos and their descendants. It is also significant to the Chinatown community and to the countless Angelenos of all ethnicities who were born or treated at the hospital over the past 155 years.

The French Colony vanished with virtually no traces during the postwar era. There are NO surviving buildings from the former Colony proper, and the core of the community - the original intersection of Alameda and Aliso Streets - gave way to freeway development in 1953. Only two surviving street names - Vignes and Ducommun - testify to the fact that it ever existed.

This hospital is one of a VERY few rare survivors related to the Colony. Must it go the way of California’s first commercial vineyard, the original headquarters of California’s oldest corporation, and the dozen or so hotels that formerly catered to French newcomers (all of which formerly stood in the Colony)? Surely a solution can be found that doesn’t require its destruction.

Sincerely,

C.C. de Vere

Nerd-in-Chief, frenchtownconfidential.blogspot.com