On this day in 1789, the French Revolution began.

I an pretty open about having a complicated relationship with La Fête Nationale/Bastille Day. My dad is a descendant of an earlier French monarch, which makes both Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette my very distant cousins. My mom's family comes from centuries of French peasant stock.

Still, I wish I could take a time machine to Old LA on this day. The French community put on quite a Bastille Day celebration.

In fact, it used to be a pretty big deal in LA.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1881 |

One of the earliest references I can find lists the parade route: Aliso to Arcadia, Main to the Plaza, then to Spring, Spring to Second, Second to Fort (Broadway), Fort to Fourth, Fourth to Main, Main to the junction with Spring, and to the Turnverein Hall for speeches. "A representation of the Bastille" (i.e. a very early parade float) was included in the procession.

This route would have effectively started in the French Colony, gone to the Plaza, doubled back and wound through downtown, ending up where the Convention Center parking lot is today. For comparison, the Rose Parade follows a roughly 5.5 mile route.

Two of the speakers were Pascal Ganée and Georges Le Mesnager, who was quite well known for his speeches! More on that in a minute.

Bastille Day 1881 concluded with a banquet at the Pico House, prepared under one of LA's early celebrity chefs, Victor Dol.

On this day in 1882, the festivities began with a 21-gun salute at sunrise from Fort Hill. The Mayor, the President of the City Council, "delegates from fire companies and civil societies", French citizens of varying prominence, and a beauty queen - the Goddess of Liberty - all made appearances.

The Goddess of Liberty chosen for the event, by the way, happened to be 14-year-old Narcisse Sentous, eldest daughter of Jean Sentous. She was carried in a "Car of Liberty" with several maids of honor, all girls from the French Colony.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1882 (snippet of much longer article) |

The parade procession was big enough to have two divisions, both made up of prominent citizens and local societies. Besides the Car of Liberty, another car had Marie Deleval representing France, Mathilde Reynaud representing the United States, Honoré Penelon (eight-year-old son of the late Henri Penelon) dressed as the Marquis de Lafayette, and ten-year-old Auguste Lemasne dressed as George Washington. Rounding up the rear were citizens riding donkeys in tribute to the city's butchers.

Eugene Meyer, the "President of the Day" (i.e. Grand Marshal) and then-Agent for the French consulate, gave a speech in French and introduced Frank Howard (who gave a quick history lesson on Bastille Day in English). "The Star-Spangled Banner" was sung, the band played, "La Marseillaise" was sung, and Georges Le Mesnager gave a speech in French.

And that wasn't all. A large model of the Bastille had been built on Fort Hill. After the sun went down, it was stormed and set on fire. (Good thing two fire companies were there!)

The day concluded with a party at Armory Hall.

In 1886, the French Colony invited the editor of the Los Angeles Herald to attend the Bastille Day celebration. He had a prior commitment in Long Beach that day, but thanked the French Colony in the newspaper.

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1886 The newspaper did still cover the event, of course. In spite of a half-hour rainstorm (an extreme rarity during a Southern California summer), the parade went on, although many people who had planned to join the parade waited inside the French Theatre for the rest of the day's events. The President of the Day was Jean-Louis Sainsevain this time - and again, one of the last speeches was given by Georges Le Mesnager. The biggest celebration of them all was held in 1889 - the 100th anniversary of the French Republic. Besides the usual festivities, an extravagant banquet and ball was held at the Pico House, then owned by Pascal Ballade and renamed the National Hotel. The speech Georges Le Mesnager gave on this day was particularly well remembered by French Angelenos - and you can read most of it (thoughtfully translated into English by the Los Angeles Herald) here. |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1891. |

An interesting footnote to the 1891 celebration is that one of the vocalists was J.P. Goytino, who despite having some musical talent was also a highly problematic newspaper editor/slumlord/all-around dirtbag. Goytino is perhaps most notorious for stopping issuance of a marriage license five years later when his extremely wealthy father-in-law, Joseph Mascarel, sought to legally marry his common-law second wife. (He needn't have bothered; Mascarel left most of his fortune to his grandchildren from his first marriage.) I could do a pretty ugly deep dive on Goytino, but David Kimbrough already did a very thorough one on Facebook (warning: it's a 12-parter).

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1900 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1901 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Los Angeles Herald, 1908 |

|

| Hollywood Citizen-News, 1940 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1947 |

After the war, Bastille Day was back - and hosted by the Los Angeles Breakfast Club!

|

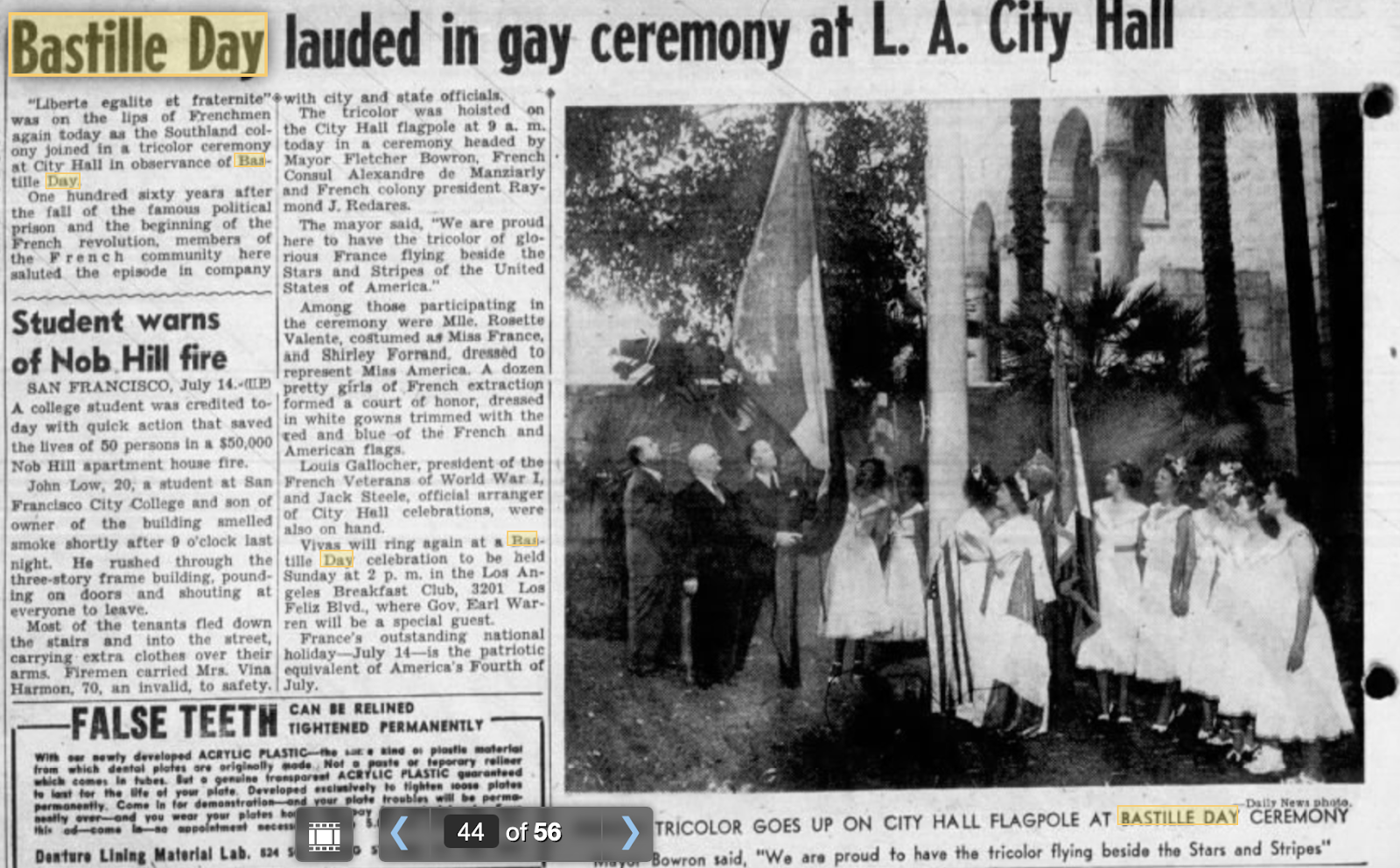

| Los Angeles Daily News, 1949 |

Los Angeles Times, 1951  |

| Los Angeles Times, 1957 |

|

| Highland Park News-Herald and Journal, 1957 |

|

| Los Angeles Times, 1960 |

Bastille Day was a big enough event to merit an annual flag ceremony at City Hall and draw a crowd of thousands to the Colony’s celebration. That certainly isn't the case now, and I fully expect Mayor Garcetti to ignore Bastille Day again, as Mayors of Los Angeles have tended to do for years.