When the words "French sea captain" and "Los Angeles" are mentioned in the same sentence, the name of former Mayor Joseph Mascarel comes to mind (for those of us who know local history, anyway).

But there were others.

One other French sea captain (and there were a few) who settled in Los Angeles was Charles Baric.

Captain Baric and his wife Sophie lived in the Plaza, close to the Old Plaza Church.

In early LA, roofs were commonly made of clay and reed wattle. In spite of the mild climate, they did still have to be waterproofed, and tar did the trick. One of the biggest sources of tar, if not THE biggest, was the La Brea Tar Pits. At one point, Captain Baric owned the land where the tar pits are located, and sold tar for roofing purposes. (Who understands the importance of waterproofing better than someone responsible for a ship?)

Records on Captain Baric are scarce (even Ancestry.com came up with nothing), but we do know he arrived in Los Angeles in 1834, was often called "Don Carlos", was a trader in addition to a ship's captain, and supported the Americans in the Mexican-American War.

The Barics' adobe home was later demolished to make way for a mixed-use building called the Plaza House.

Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Saturday, February 11, 2017

Sophie Baric's Gruesome Discovery

Sophie Baric* and her sea-captain husband, Charles Baric, lived in the Plaza, close to the Old Plaza Church. They were good friends with their neighbor Nicholas Finck, a German immigrant who ran a small general store out of his modest house.

In the days before trucks and delivery vans, LA's shop owners would have to go to the port at San Pedro to buy new stock from whichever ships had arrived. Whenever Finck had to go on a buying trip, he locked up the shop and left the key with the Barics for safekeeping.

One day in 1841, Sophie noticed that Finck's door wasn't open. Finck's door was ALWAYS open during business hours, unless he was down at the port.

But he couldn't be at the port. As the wife of a sea captain, Sophie knew when the trading vessels were in port. And she knew no trading vessels were docked at San Pedro that day. Finck certainly hadn't come by to drop off his key, either.

Three days passed. Finck's door remained shut. Finally, the tiny Frenchwoman decided to cross the plaza and see what was wrong. (Captain Baric was out of town.)

She couldn't see or hear anything through the keyhole. But she smelled something revolting.

The Los Angeles Herald, recounting the story in 1899, colorfully stated that "to her nostrils came an odor at once foul and forbidding that made her limbs to quake, her hair to creep, her gorge to rise, and her blood to curdle."

Sophie went straight to Don Manuel Requena (a member of the City Council), telling him she feared the worst. The councilman called upon Don Ygnacio Coronel. Coronel, an officer of the court, summoned three alguaciles (in modern English, police officers or bailiffs). When three rounds of knocking yielded no response, they broke down the door.

Poor Nicholas Finck. He was lying near his shop counter, still clutching his magnifying glass, in a pool of his own blood. Rigor mortis had set in, and he was already decomposing. The killers had fashioned a gun barrel into a bludgeon and beaten in Finck's head.

Finck had clearly been conducting business when he was murdered. The assailants had ransacked the shop and Finck's living quarters in the back (some items were clearly missing; many were just tossed around the tiny store). Bloody footprints were everywhere.

In the rear of the building, Don Coronel discovered Finck's mastiff - gaunt and weak (the killers had chained him in the rear courtyard with no food or water), but still alive.

The Herald commented:

Finck's mastiff proved instrumental in cracking the case. Don Requena and Don Coronel noticed the dog growling at one particular suspect, Santiago Linares. When they brought Linares close to the dog, the poor creature snarled and leapt onto him (and might have killed him, had he not been pulled away quickly).

Linares attempted to use his mistress, Eugenia Valencia, as his alibi. Which backfired horribly, since the officers sent to retrieve Eugenia discovered quite a few things stolen from Finck when they searched her home. Despite coming from a family of degenerate criminals, Eugenia cracked under pressure and confessed, implicating Linares, her brother Ascencio, Jose Duarte, and herself as the guilty parties.

Had Sophie not checked on her neighbor when she did, Finck's dog probably would have died, and the killers would very likely have gone on to murder someone else.

*Believe me, I have looked and looked for Sophie's maiden name. Even Ancestry.com came up with nothing.

In the days before trucks and delivery vans, LA's shop owners would have to go to the port at San Pedro to buy new stock from whichever ships had arrived. Whenever Finck had to go on a buying trip, he locked up the shop and left the key with the Barics for safekeeping.

One day in 1841, Sophie noticed that Finck's door wasn't open. Finck's door was ALWAYS open during business hours, unless he was down at the port.

But he couldn't be at the port. As the wife of a sea captain, Sophie knew when the trading vessels were in port. And she knew no trading vessels were docked at San Pedro that day. Finck certainly hadn't come by to drop off his key, either.

Three days passed. Finck's door remained shut. Finally, the tiny Frenchwoman decided to cross the plaza and see what was wrong. (Captain Baric was out of town.)

She couldn't see or hear anything through the keyhole. But she smelled something revolting.

The Los Angeles Herald, recounting the story in 1899, colorfully stated that "to her nostrils came an odor at once foul and forbidding that made her limbs to quake, her hair to creep, her gorge to rise, and her blood to curdle."

Sophie went straight to Don Manuel Requena (a member of the City Council), telling him she feared the worst. The councilman called upon Don Ygnacio Coronel. Coronel, an officer of the court, summoned three alguaciles (in modern English, police officers or bailiffs). When three rounds of knocking yielded no response, they broke down the door.

Poor Nicholas Finck. He was lying near his shop counter, still clutching his magnifying glass, in a pool of his own blood. Rigor mortis had set in, and he was already decomposing. The killers had fashioned a gun barrel into a bludgeon and beaten in Finck's head.

Finck had clearly been conducting business when he was murdered. The assailants had ransacked the shop and Finck's living quarters in the back (some items were clearly missing; many were just tossed around the tiny store). Bloody footprints were everywhere.

In the rear of the building, Don Coronel discovered Finck's mastiff - gaunt and weak (the killers had chained him in the rear courtyard with no food or water), but still alive.

The Herald commented:

The discovery of this murder was followed by wild excitement in the pueblo. The resident foreigners - that is, not Spanish-Americans - as usual, acted as if the crime were a result of race antagonism, rather than personal motive, and they called loudly for vengeance, and were not far from creating an incendiary uprising. Guards were posted to watch over the public safety, an ordinance was issued requiring citizens to be within doors by 10 o'clock at night and a volunteer guard was placed over the jail, besides which a small detachment of soldiers were sent thither from Santa Barbara.(Sooo...in other words, LA hasn't changed all that much.)

Finck's mastiff proved instrumental in cracking the case. Don Requena and Don Coronel noticed the dog growling at one particular suspect, Santiago Linares. When they brought Linares close to the dog, the poor creature snarled and leapt onto him (and might have killed him, had he not been pulled away quickly).

Linares attempted to use his mistress, Eugenia Valencia, as his alibi. Which backfired horribly, since the officers sent to retrieve Eugenia discovered quite a few things stolen from Finck when they searched her home. Despite coming from a family of degenerate criminals, Eugenia cracked under pressure and confessed, implicating Linares, her brother Ascencio, Jose Duarte, and herself as the guilty parties.

Had Sophie not checked on her neighbor when she did, Finck's dog probably would have died, and the killers would very likely have gone on to murder someone else.

*Believe me, I have looked and looked for Sophie's maiden name. Even Ancestry.com came up with nothing.

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Georges Le Mesnager: LA's Favorite Fighting Frenchman

Georges Le Mesnager arrived in California in 1867. He was sixteen years old.

In July of 1870, the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Travel time and expenses be damned, nineteen-year-old Georges immediately packed up and went back to France to enlist in the French Army and defend his homeland under General de Chanzy.

Georges returned to LA after the war ended, and became a U.S. citizen at age 21. He worked as a notary and court translator (remember, French was more commonly spoken than English in 1870s LA), owned a store on Commercial Street, and owned property at 1660 N. Main Street.

Georges married Concepción Olarra (sometimes styled "O'Lara"). It isn't clear whether she was Mexican, Spanish, or born in the New World to Spanish parents - and it's possible she had Irish ancestry. Unfortunately I cannot find any records of her birth or death. Records on Ancestry do show other Olarras (none of whom I could conclusively tie to Concepción) living in 19th century Mexico.

Letters published in La Crónica between 1876-1878 indicate that Concepción was probably a native Spanish speaker. This would not have been a deterrent to the multilingual Georges. They had four children: Louis, George, Louise, and Jeanne.

Georges' intelligence and linguistic abilities served him well when he became the editor of the weekly French-language newspaper Le Progres, founded in 1883 and headquartered on New High Street. Le Progrés was politically independent and so popular with Francophone readers (in spite of strong competition from L'Union Nouvelle) that copies of the newspaper trickled back to France. At least one other French Angeleno, Felix Violé, was inspired to move to Los Angeles after reading a copy of Le Progrés at the home of a relative with friends in California (but we'll get to the Violé family later).

Like so many of his countrymen in Southern California, Georges got into wine and liquor production. In fact, Georges soon had to give up editing Le Progrés because his wine business kept him too busy. His grapes were eventually grown in Glendale, but his Hermitage Winery stood at 207 N. Los Angeles Street, close to the heart of Frenchtown. (And now the site is the unattractive Los Angeles Mall. Doesn't seem like a fair trade, does it?)

He was acting president of the Légion Français for three years, but stepped down in 1895 (he was given the title of honorary president as a token of the Légion's gratitude).

In 1894, at the age of 43, Georges married Marie du Creyd Bremond. Marie was 32 and a fellow French immigrant. They had one child together: Evon.

Georges' real estate holdings had their own challenges. In 1896, he sued the city over a dispute regarding streets in the Mesnager housing tract. Two years later, he was threatened by a trigger-happy tenant, Emil Rombaud, and asked for police protection. The same year, the Le Mesnagers sued a different tenant for damaging a rented vineyard. And Georges' more unusual land holdings included partial ownership of the Ventura County islands of San Nicolas and Anacapa. (If you read Island of the Blue Dolphins in fourth grade, it's a fictionalized account of San Nicolas' last Native American inhabitant, Juana Maria.)

Georges bought a huge parcel of land in what is now Glendale, built a stone barn, and planted grapevines. These days, Deukmejian Wilderness Park preserves the land where the Le Mesnagers grew those grapes.

When Georges' stone barn was damaged by a fire and a flood, his son Louis converted it into a farmhouse. The Le Mesnager family lived in the stone house until 1968.

Georges was so well acquainted with "King of Calabasas" Miguel Leonis that he was one of two executors of Leonis' estate. (Georges made wine and liquor. Leonis liked to drink. What a coincidence.)

The French community held a huge celebration of Bastille Day's centennial on July 14, 1889. Georges Le Mesnager delivered a speech in French at the event.

On September 21, 1892, the French community celebrated the centennial of the French Republic. The celebration - even bigger and more spectacular than Bastille Day's centennial three years earlier - featured Georges as the French-language speaker of the day (this being multicultural LA, someone else gave a speech in English). According to Le Guide Français, published forty years later, "his eloquent and fiery speech still rings in the ears of the older members of the colony."

World War One broke out in 1914. Georges didn't hesitate to return to France and re-enlist in the French Army. He was 64 years old at the time.

Georges didn't even try to negotiate this with his family. It was too important to him. He simply told his oldest son, "Well, my dear Louis, I am leaving for the war. France needs every one of her sons."

Louis objected, "But you are too old to fight."

Georges didn't care. "I promised in 1870 to be there if France were invaded again, and I want to keep my promise."

Georges sent Marie to visit their daughter Louise in Catalina for a week. He asked their youngest daughter, Evon, to gently break the news to her mother when she returned. Marie was very upset, but reasoned "maybe it is all for the best" in a letter to Georges.

So, Georges traveled to New York and set sail for France. As soon as he arrived, he re-enlisted as a private and was assigned to the 106th Infantry.

It wasn't an easy task. French authorities were highly suspicious of anyone entering the country during wartime, and Georges was detained by police at the dock. According to the Ocala Evening Star, a gendarme laughed at his plan to rejoin the army. Georges simply reached into his pocket and took out his prized Legion d'honneur medal - the highest military or civilian honor a French citizen can receive.

"I came from America in 1870 and fought for France and they gave me this. I've come back to fight again."

With the Germans rapidly approaching Paris, soldiers were desperately needed. This was not the time to quibble over a willing volunteer's age. The gendarme kindly directed him to a recruiting station down the street.

The recruiter was hesitant. A 64-year-old private in the infantry was pretty much unheard of. But Georges showed the recruiter his Legion d'honneur medal, and he was on a troop train that very night.

After just seven days on the front, Georges was shot through the arm and hospitalized for a month. He was quickly promoted to sergeant for gallant conduct.

Georges spent months in the trenches at the seemingly endless battle of Verdun. One day, the unthinkable happened: the 106th ran dangerously low on ammunition.

The colonel asked for a volunteer to retrieve more ammunition. It was a suicide mission. But Georges volunteered, and in spite of the German army's best attempts to shoot him down, succeeded. For his courage, he was given the croix de guerre. The colonel told his regiment "Every soldier should have the courage and spirit of this veteran comrade."

One night, Georges was talking to his regimental adjutant when a German artillery shell passed between them, landed nearby, and exploded.

Both men survived, although the explosion sent them flying. Georges regained consciousness under a tree, retrieved parts of the spent artillery shell, brought them back to the trench, and showed them to his troops.

"It was nothing at all, nothing at all," he laughed. "Don't ever be afraid of a shell like this one. It's only the shell that hits you that you need to dread."

The colonel overheard this remark, and recommended Georges for further honors. He received another medal, the palme.

In a later battle, a massive German soldier tried to take out the aging Georges - who ran him through. For this, he received yet another medal, this one for bravery in hand-to-hand combat.

Georges' courage in the battles of Eparges, Chemin des Dames, and the trancheé de Calonne did not escape notice, and he was wounded five times during the war.

Georges' family knew nothing of this until Marie read about his heroics in a book published after the war's end. She told the Tonopah Daily Bonanza "It is characteristic of my husband that he should say nothing of being wounded. He never writes anything about himself. It is always about the bravery of others. The only information of personal nature I had from him was that his weight had decreased, but he always insisted he was well. He did write from a hospital, but stated he was there on business. He might be wounded a dozen times, but he never would tell us about it."

(That article, by the way, was unkindly titled "Old Man Runs Away From Home to Fight." The Ogden Standard also published Marie's comments under a different title.)

In 1916, Georges - now a Sergeant Major - was granted a leave of absence, and returned to Los Angeles. During his leave, he focused his energies on two important tasks: defending France from scapegoating, and raising funds for the wounded and maimed soldiers in his regiment. The French community and its supporters were very generous, and Georges was able to bring a good amount of money back to France when he rejoined his regiment.

Besides medals, Georges' leadership and courage earned him the praise of Generals Foch, Pershing, and de Castelnau. He was also appointed lieutenant flag bearer of the 106th Infantry.

As the war drew closer to an end, Georges - now a Lieutenant - was transferred to special duty under General Pershing. In this role, he acted as a liaison and translator for one of the French army divisions that trained with the American military. He led the Alsatian veterans when the army entered Strasbourg.

Georges told the Ocala Evening Star "I couldn't remain quiet when the war broke out. Ever since 1871 I had itched to get back at the Germans...It was one of the happiest days of my life when the United States, my country, joined in the war against Germany on the side of the country of my birth."

While Georges was away fighting for France, his family founded the Le Mesnager Land and Water Company. They secured partial rights to the Verdugo Wash stream, which supplied water to the vineyard.

Georges returned to Los Angeles after the war ended. After four years of the war to end all wars (need I mention he was 68 when it ended?), he'd earned a well-deserved rest. But he had one thing left to do.

After returning to his home in Echo Park, Georges founded the Section Nivelle des Véterans Français de Los Angeles - a society for LA's French war veterans. He also served as its first president.

Finally, Georges decided it was time to retire. He bought a mansion in the Verdugo Hills called Sans Souci ("without a care" in French), which should not be confused with the Sans Souci fantasy castle in Hollywood.

In 1921, Georges was partially paralyzed by an apoplectic stroke. He knew it was the beginning of the end, and decided to spend his last days in France. The following year, he returned to Mayenne with Marie and Evon. Georges bought another grand property: the Chateau de Kerleón.

At six a.m. on September 6, 1923, Georges stood up and died in his nurse's arms.

Georges was buried with full military honors. Every war veterans' association flew its flag at the funeral. This being small-town France, the funeral was held before the very altar where he had been baptized so many years earlier. Colonel Oblet recorded Georges' considerable military accomplishments on his tombstone.

The Chateau de Kerleón was, tragically, destroyed by Nazi bombing in World War II.

Incredibly, the Le Mesnagers' old stone house is still standing at 3429 Markridge Road in Glendale and is being converted into a nature center. There is also a Mesnagers Street in Los Angeles.

Surviving sites associated with the French community are RARE (as of today, I've mapped FOUR HUNDRED, only a handful of which still exist). And yet, somehow, it doesn't seem like enough.

I, for one, would pay good money to see Georges Le Mesnager's story on the silver screen (and I can't sit through war movies).

*Most sources Anglicize Georges' name to George. Since older resources give his name as Georges, which is the correct form in French anyway, I'm calling him Georges.

In July of 1870, the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Travel time and expenses be damned, nineteen-year-old Georges immediately packed up and went back to France to enlist in the French Army and defend his homeland under General de Chanzy.

Georges returned to LA after the war ended, and became a U.S. citizen at age 21. He worked as a notary and court translator (remember, French was more commonly spoken than English in 1870s LA), owned a store on Commercial Street, and owned property at 1660 N. Main Street.

Georges married Concepción Olarra (sometimes styled "O'Lara"). It isn't clear whether she was Mexican, Spanish, or born in the New World to Spanish parents - and it's possible she had Irish ancestry. Unfortunately I cannot find any records of her birth or death. Records on Ancestry do show other Olarras (none of whom I could conclusively tie to Concepción) living in 19th century Mexico.

Letters published in La Crónica between 1876-1878 indicate that Concepción was probably a native Spanish speaker. This would not have been a deterrent to the multilingual Georges. They had four children: Louis, George, Louise, and Jeanne.

Georges' intelligence and linguistic abilities served him well when he became the editor of the weekly French-language newspaper Le Progres, founded in 1883 and headquartered on New High Street. Le Progrés was politically independent and so popular with Francophone readers (in spite of strong competition from L'Union Nouvelle) that copies of the newspaper trickled back to France. At least one other French Angeleno, Felix Violé, was inspired to move to Los Angeles after reading a copy of Le Progrés at the home of a relative with friends in California (but we'll get to the Violé family later).

Like so many of his countrymen in Southern California, Georges got into wine and liquor production. In fact, Georges soon had to give up editing Le Progrés because his wine business kept him too busy. His grapes were eventually grown in Glendale, but his Hermitage Winery stood at 207 N. Los Angeles Street, close to the heart of Frenchtown. (And now the site is the unattractive Los Angeles Mall. Doesn't seem like a fair trade, does it?)

He was acting president of the Légion Français for three years, but stepped down in 1895 (he was given the title of honorary president as a token of the Légion's gratitude).

In 1894, at the age of 43, Georges married Marie du Creyd Bremond. Marie was 32 and a fellow French immigrant. They had one child together: Evon.

Georges' real estate holdings had their own challenges. In 1896, he sued the city over a dispute regarding streets in the Mesnager housing tract. Two years later, he was threatened by a trigger-happy tenant, Emil Rombaud, and asked for police protection. The same year, the Le Mesnagers sued a different tenant for damaging a rented vineyard. And Georges' more unusual land holdings included partial ownership of the Ventura County islands of San Nicolas and Anacapa. (If you read Island of the Blue Dolphins in fourth grade, it's a fictionalized account of San Nicolas' last Native American inhabitant, Juana Maria.)

Georges bought a huge parcel of land in what is now Glendale, built a stone barn, and planted grapevines. These days, Deukmejian Wilderness Park preserves the land where the Le Mesnagers grew those grapes.

When Georges' stone barn was damaged by a fire and a flood, his son Louis converted it into a farmhouse. The Le Mesnager family lived in the stone house until 1968.

Georges was so well acquainted with "King of Calabasas" Miguel Leonis that he was one of two executors of Leonis' estate. (Georges made wine and liquor. Leonis liked to drink. What a coincidence.)

The French community held a huge celebration of Bastille Day's centennial on July 14, 1889. Georges Le Mesnager delivered a speech in French at the event.

On September 21, 1892, the French community celebrated the centennial of the French Republic. The celebration - even bigger and more spectacular than Bastille Day's centennial three years earlier - featured Georges as the French-language speaker of the day (this being multicultural LA, someone else gave a speech in English). According to Le Guide Français, published forty years later, "his eloquent and fiery speech still rings in the ears of the older members of the colony."

World War One broke out in 1914. Georges didn't hesitate to return to France and re-enlist in the French Army. He was 64 years old at the time.

Georges didn't even try to negotiate this with his family. It was too important to him. He simply told his oldest son, "Well, my dear Louis, I am leaving for the war. France needs every one of her sons."

Louis objected, "But you are too old to fight."

Georges didn't care. "I promised in 1870 to be there if France were invaded again, and I want to keep my promise."

Georges sent Marie to visit their daughter Louise in Catalina for a week. He asked their youngest daughter, Evon, to gently break the news to her mother when she returned. Marie was very upset, but reasoned "maybe it is all for the best" in a letter to Georges.

So, Georges traveled to New York and set sail for France. As soon as he arrived, he re-enlisted as a private and was assigned to the 106th Infantry.

It wasn't an easy task. French authorities were highly suspicious of anyone entering the country during wartime, and Georges was detained by police at the dock. According to the Ocala Evening Star, a gendarme laughed at his plan to rejoin the army. Georges simply reached into his pocket and took out his prized Legion d'honneur medal - the highest military or civilian honor a French citizen can receive.

"I came from America in 1870 and fought for France and they gave me this. I've come back to fight again."

With the Germans rapidly approaching Paris, soldiers were desperately needed. This was not the time to quibble over a willing volunteer's age. The gendarme kindly directed him to a recruiting station down the street.

The recruiter was hesitant. A 64-year-old private in the infantry was pretty much unheard of. But Georges showed the recruiter his Legion d'honneur medal, and he was on a troop train that very night.

After just seven days on the front, Georges was shot through the arm and hospitalized for a month. He was quickly promoted to sergeant for gallant conduct.

Georges spent months in the trenches at the seemingly endless battle of Verdun. One day, the unthinkable happened: the 106th ran dangerously low on ammunition.

The colonel asked for a volunteer to retrieve more ammunition. It was a suicide mission. But Georges volunteered, and in spite of the German army's best attempts to shoot him down, succeeded. For his courage, he was given the croix de guerre. The colonel told his regiment "Every soldier should have the courage and spirit of this veteran comrade."

One night, Georges was talking to his regimental adjutant when a German artillery shell passed between them, landed nearby, and exploded.

Both men survived, although the explosion sent them flying. Georges regained consciousness under a tree, retrieved parts of the spent artillery shell, brought them back to the trench, and showed them to his troops.

"It was nothing at all, nothing at all," he laughed. "Don't ever be afraid of a shell like this one. It's only the shell that hits you that you need to dread."

The colonel overheard this remark, and recommended Georges for further honors. He received another medal, the palme.

In a later battle, a massive German soldier tried to take out the aging Georges - who ran him through. For this, he received yet another medal, this one for bravery in hand-to-hand combat.

Georges' courage in the battles of Eparges, Chemin des Dames, and the trancheé de Calonne did not escape notice, and he was wounded five times during the war.

Georges' family knew nothing of this until Marie read about his heroics in a book published after the war's end. She told the Tonopah Daily Bonanza "It is characteristic of my husband that he should say nothing of being wounded. He never writes anything about himself. It is always about the bravery of others. The only information of personal nature I had from him was that his weight had decreased, but he always insisted he was well. He did write from a hospital, but stated he was there on business. He might be wounded a dozen times, but he never would tell us about it."

(That article, by the way, was unkindly titled "Old Man Runs Away From Home to Fight." The Ogden Standard also published Marie's comments under a different title.)

In 1916, Georges - now a Sergeant Major - was granted a leave of absence, and returned to Los Angeles. During his leave, he focused his energies on two important tasks: defending France from scapegoating, and raising funds for the wounded and maimed soldiers in his regiment. The French community and its supporters were very generous, and Georges was able to bring a good amount of money back to France when he rejoined his regiment.

Besides medals, Georges' leadership and courage earned him the praise of Generals Foch, Pershing, and de Castelnau. He was also appointed lieutenant flag bearer of the 106th Infantry.

As the war drew closer to an end, Georges - now a Lieutenant - was transferred to special duty under General Pershing. In this role, he acted as a liaison and translator for one of the French army divisions that trained with the American military. He led the Alsatian veterans when the army entered Strasbourg.

Georges told the Ocala Evening Star "I couldn't remain quiet when the war broke out. Ever since 1871 I had itched to get back at the Germans...It was one of the happiest days of my life when the United States, my country, joined in the war against Germany on the side of the country of my birth."

While Georges was away fighting for France, his family founded the Le Mesnager Land and Water Company. They secured partial rights to the Verdugo Wash stream, which supplied water to the vineyard.

Georges returned to Los Angeles after the war ended. After four years of the war to end all wars (need I mention he was 68 when it ended?), he'd earned a well-deserved rest. But he had one thing left to do.

After returning to his home in Echo Park, Georges founded the Section Nivelle des Véterans Français de Los Angeles - a society for LA's French war veterans. He also served as its first president.

Finally, Georges decided it was time to retire. He bought a mansion in the Verdugo Hills called Sans Souci ("without a care" in French), which should not be confused with the Sans Souci fantasy castle in Hollywood.

In 1921, Georges was partially paralyzed by an apoplectic stroke. He knew it was the beginning of the end, and decided to spend his last days in France. The following year, he returned to Mayenne with Marie and Evon. Georges bought another grand property: the Chateau de Kerleón.

At six a.m. on September 6, 1923, Georges stood up and died in his nurse's arms.

Georges was buried with full military honors. Every war veterans' association flew its flag at the funeral. This being small-town France, the funeral was held before the very altar where he had been baptized so many years earlier. Colonel Oblet recorded Georges' considerable military accomplishments on his tombstone.

The Chateau de Kerleón was, tragically, destroyed by Nazi bombing in World War II.

Incredibly, the Le Mesnagers' old stone house is still standing at 3429 Markridge Road in Glendale and is being converted into a nature center. There is also a Mesnagers Street in Los Angeles.

Surviving sites associated with the French community are RARE (as of today, I've mapped FOUR HUNDRED, only a handful of which still exist). And yet, somehow, it doesn't seem like enough.

I, for one, would pay good money to see Georges Le Mesnager's story on the silver screen (and I can't sit through war movies).

*Most sources Anglicize Georges' name to George. Since older resources give his name as Georges, which is the correct form in French anyway, I'm calling him Georges.

Thursday, January 12, 2017

The Forgotten Beaudry Brother

We've covered Prudent Beaudry. But Victor, the youngest of the eight Beaudry siblings, is completely forgotten today.

Like his older brothers before him, Victor was born in Quebec in 1829 and educated in the best schools Montreal and New York had to offer. And like the rest of his brothers, he had a head for business and spoke fluent English. Since he arrived rather late in his parents' lives, Victor faced a challenge his brothers did not: he was only three years old when their father died.

In the late 1840s (sources disagree on whether it was before or after the Gold Rush began), Victor (now in his late teens) moved to San Francisco and established a successful shipping and commission business. Prudent, who was thirteen years older than Victor, later joined him, and the brothers then got into the ice business.

By 1850*, Victor was living in Los Angeles. He got back into the ice business with Damien Marchesseault, harvesting ice in the San Bernardino mountains and shipping it via mule train to Los Angeles. From the port of San Pedro, some of their ice was shipped to saloons in the faraway, but no less thirsty, city of San Francisco. Their ice house is long gone, but the area is still called Ice House Canyon. Victor also did some mining in the San Gabriel Valley and co-founded the Santa Anita Mining Company with Marchesseault in 1858. From 1855 to 1861, Victor managed Prudent's many business interests, at one point remodeling the aging Beaudry Block into Southern California's finest commercial building. He became a U.S. citizen in 1858 (beating older brother Prudent to citizenship by five years).

Three years later, Victor received a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and joined the First Regiment of Infantry in the United States Army, fighting for the Union cause. He remained in the Army until the bitter end of the Civil War, suffering health problems for much of his life as a result of his wartime experiences.

After the war, several of Victor's good friends from the Army were stationed at Camp Independence in Inyo County, and suggested he open a store there. This was a natural enough task for Victor, since he came from a family of successful merchants.

Victor soon acquired an interest in the Cerro Gordo silver mines, partnering with Mortimer Belshaw. Due to the mines' prodigious output (An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County puts the figure at 5,000,000 pounds of bullion per year), 400 mules were needed to haul the bullion 200 miles to San Pedro, where it would be sent via ship to San Francisco. Remi Nadeau (who had started his empire by borrowing $600 from Prudent to buy a freight wagon and mules) formed the Cerro Gordo Freighting Company with Victor and Belshaw. Years later, when Nadeau liquidated most of his freighting company's equipment, it was largely purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company - which just so happened to be partially owned by the Beaudry brothers. But we'll get into the details when we get to Remi Nadeau.

Because the Cerro Gordo mines stimulated so much business in the area (and on the route to LA), the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad was built. Before too long, the Southern Pacific Railroad also branched out to the Mojave Desert.

Victor returned to Montreal in 1872. The following year, he married the Sheriff of Montreal's daughter, Mary Angelena Le Blanc. Before long, the couple had five children (Victor, Oscar, Abel, Alva, and Mathilda). Victor returned to Los Angeles with his wife and children in 1881, building a house at 405 Temple Street (near Montreal Street, which was later renamed Hill Street) and working with Prudent in real estate development. You know this story. Angelino Heights, Temple Street Cable Railway, half of modern-day downtown...I won't rehash it here. Victor's name appeared in the real estate section of local newspapers almost as often as Prudent's (mostly regarding properties in the Angelino Heights and Beaudry Water Works tracts). The April 8, 1883 Los Angeles Daily Herald even lists Victor as the seller of Beaudry Park to the Los Angeles Infirmary (aka St. Vincent's Hospital).

Over the years, city directories and voter rolls simply listed Victor's occupation as "capitalist".

The Beaudrys returned to Montreal in 1886. Victor had experienced health issues since his stint in the Army, and by this time was suffering from inflammatory rheumatism. He passed away in Montreal on March 7, 1888. Prudent was notified by telegram that evening, and Victor's obituary appeared in the following morning's Los Angeles Herald.

For a few years after his death, Prudent and F.W. Wood, executors of Victor's estate, slowly liquidated Victor's impressive real estate holdings. (In November 1888, they were sued over an alleged one-fourth interest in the Old Cemetery tract Victor held. One of the plaintiffs was George S. Patton Sr. - General Patton's father.) Prudent is well known to local historians as a prodigious developer and real estate agent, but Victor's real estate interests were nothing to sneeze at.

The house on Temple Street is long gone. Today, the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels takes up most of the block. The former site of Victor's house is very close to the Cathedral's gift shop.

When Victor is remembered at all, he is remembered as Prudent's brother. While partnering with Prudent made him even wealthier, Victor accomplished quite a lot on his own and with different business partners. He should be remembered for his own merits, not merely for being the baby brother of two mayors.

*One source says Victor spent a few years in Nicaragua for business purposes. It does sound like something a Beaudry would do - however, I can't find a proper source citation, and the older sources say 1850. In the absence of proof, I'll leave 1850 as the date.

Wednesday, January 4, 2017

Joseph Mascarel and the Lazard Street Poltergeist

Despite his gruff, no-nonsense demeanor, former Mayor Joseph Mascarel was not immune to odd occurrences. The September 6, 1889 edition of the Los Angeles Daily Herald details a bizarre three-night incident at the Mascarel residence. At that point, the former mayor lived at 99 Lazard Street (incidentally, Lazard Street was named after another prosperous French businessman - Solomon Lazard, who we will meet again later).

One night around 9pm, after Mascarel and his common-law second wife, Maria, had gone to bed, three loud raps were heard on the rear door of their house. He later described it as sounding like the back door had been slammed violently three times in rapid succession. However, the back door, and the screen door in front of it, were closed and locked.

Mascarel called out "Who is there?" (the article didn't specify whether he spoke in French or Spanish) and checked the back porch. Finding no one there (and it was a brightly moonlit night), he went back to bed. The raps promptly repeated - this time louder and more distinct, and the raps continued for longer. The last rap rattled the windows and woke everyone in the house. Again, no one was on the back porch.

Mascarel tried leaving the inside back door open, hoping to catch the culprit. Ten to fifteen minutes later, the rapping began again. This time Mascarel stepped onto the back porch before the rapping ended - and again, no one was there.

The following morning, Maria and the couple's children insisted the strange noises must have been the work of spirits, intending to warn him or deliver a message. Mascarel had never encountered a ghost in his 73 years on Earth and wasn't about to start believing in them.

That night, the mysterious rapping noises resumed. This time they were loud enough to wake several neighbors - some of whom went inside the house to see for themselves. Nothing happened when anyone stood close to the door, but as soon as the coast was clear, the loud banging resumed.

The following day, Mascarel told this strange story to an acquaintance on the police force. (One of his daughters from his first marriage just so happened to be the wife of a police officer.) Two officers were dispatched to watch the house that night.

Meanwhile, some members of Mascarel's family insisted he consult a medium (which he was certainly not going to do). However, a neighbor took it upon herself to do so. The medium reported that the elderly former mayor could be near the end of his life, and that he should write his will as soon as possible. (Given what we know about Mascarel's unconventional domestic situation and his adult children's nasty squabbles over his large estate, I think it's safe to say that psychic was paid off.) Mascarel declined to speak with her directly.

That night, with two LAPD officers hiding in the bushes behind the house, the rapping began again. The officers ran for the porch, and a tall man dressed in black with white whiskers made a run for it. They nearly caught the man, who cursed and shouted something in French before escaping. The strange raps never happened again.

The next day, the "ghost" was all anyone in the neighborhood could talk about. Many neighbors speculated that it had all been a ruse by Mascarel's children to frighten him into changing his will (why am I not surprised?).

I wouldn't be surprised if it was also intended to scare him into finally legally marrying Maria (Mascarel's first wife, Serilda, had died in 1887).

Unfortunately, the tough, 73-year-old ex-mayor proved impossible to scare.

One night around 9pm, after Mascarel and his common-law second wife, Maria, had gone to bed, three loud raps were heard on the rear door of their house. He later described it as sounding like the back door had been slammed violently three times in rapid succession. However, the back door, and the screen door in front of it, were closed and locked.

Mascarel called out "Who is there?" (the article didn't specify whether he spoke in French or Spanish) and checked the back porch. Finding no one there (and it was a brightly moonlit night), he went back to bed. The raps promptly repeated - this time louder and more distinct, and the raps continued for longer. The last rap rattled the windows and woke everyone in the house. Again, no one was on the back porch.

Mascarel tried leaving the inside back door open, hoping to catch the culprit. Ten to fifteen minutes later, the rapping began again. This time Mascarel stepped onto the back porch before the rapping ended - and again, no one was there.

The following morning, Maria and the couple's children insisted the strange noises must have been the work of spirits, intending to warn him or deliver a message. Mascarel had never encountered a ghost in his 73 years on Earth and wasn't about to start believing in them.

That night, the mysterious rapping noises resumed. This time they were loud enough to wake several neighbors - some of whom went inside the house to see for themselves. Nothing happened when anyone stood close to the door, but as soon as the coast was clear, the loud banging resumed.

The following day, Mascarel told this strange story to an acquaintance on the police force. (One of his daughters from his first marriage just so happened to be the wife of a police officer.) Two officers were dispatched to watch the house that night.

Meanwhile, some members of Mascarel's family insisted he consult a medium (which he was certainly not going to do). However, a neighbor took it upon herself to do so. The medium reported that the elderly former mayor could be near the end of his life, and that he should write his will as soon as possible. (Given what we know about Mascarel's unconventional domestic situation and his adult children's nasty squabbles over his large estate, I think it's safe to say that psychic was paid off.) Mascarel declined to speak with her directly.

That night, with two LAPD officers hiding in the bushes behind the house, the rapping began again. The officers ran for the porch, and a tall man dressed in black with white whiskers made a run for it. They nearly caught the man, who cursed and shouted something in French before escaping. The strange raps never happened again.

The next day, the "ghost" was all anyone in the neighborhood could talk about. Many neighbors speculated that it had all been a ruse by Mascarel's children to frighten him into changing his will (why am I not surprised?).

I wouldn't be surprised if it was also intended to scare him into finally legally marrying Maria (Mascarel's first wife, Serilda, had died in 1887).

Unfortunately, the tough, 73-year-old ex-mayor proved impossible to scare.

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

He Built This City: Mayor Prudent Beaudry

Possessing boundless energy, exceptional business sagacity and foresight, Prudent Beaudry amassed five fortunes and lost four in his ventures, which were gigantic for that time, and would be considered immense today.

Have a seat, everyone...the lifetime I'm chronicling this week is best described as "epic".

Jean-Prudent Beaudry was born July 24, 1816 in Mascouche, Quebec - close to Montreal. When he was a young boy, the family moved to the neighboring town of Saint-Anne-des-Plaines.

There were five Beaudry brothers (and three Beaudry sisters). All of the Beaudry brothers worked hard and got rich, but Prudent, Jean-Louis, and Victor would make the history books. (Victor, the only other Beaudry to settle in Los Angeles, will be covered in another entry, because this one is going to be LONG.)

The Beaudrys, an industrious family of traders, sent their sons to good schools in Montreal and New York. Prudent and his brothers had the benefits of a great education and English fluency when they went into business for themselves.

Which they did, many times over.

Prudent started out in his father's mercantile business, then went to work at a different mercantile house in New Orleans, returning to Canada in 1842 to partner with one of his brothers. By 1844, he left the business to join Victor, the youngest Beaudry brother, in San Francisco. The Gold Rush was a few years away, but Victor had already established a profitable shipping and commission business in the city. Before long, the brothers were in the ice business (Victor later partnered with another future mayor, Damien Marchesseault, in distributing ice harvested in the San Bernardino Mountains). Perhaps not surprisingly for a native of Quebec, Prudent also got into the syrup business. Two years later, after Prudent had lost most of his money on real estate speculation (and more of it when insufficiently insured stock was destroyed in a fire), Los Angeles beckoned.

I'll let Le Guide Francais take it from here:

Starting with $1,100 in goods and $200 cash in a small store on Main Street, where the City Hall now stands, it is said that he cleared $2,000 in thirty days, which enabled him to take a larger store on Commercial Street. From that time on, Prudent Beaudry was one of the preeminent men of the economic, social, and political life of the Southwest.(The book, just to clarify, refers to the current City Hall, not the old Bell Block down the street. After Beaudry vacated the Commercial Street shop, Harris Newmark moved in. Ironically, Beaudry sold his dry goods business to Newmark twelve years later.)

Having earned a well-deserved vacation, Prudent left Los Angeles for Paris in 1855. The chief items on his itinerary were seeing the Exposition Universelle and consulting the great French oculist Dr. Jules Sichel. Prudent visited Montreal on his return trip to visit his brother Jean-Louis, who would serve as Mayor of Montreal for a total of ten years between 1862 and 1885. The Beaudrys, needless to say, were just as prominent in business, politics, and society in Quebec as they were in Southern California.

While Prudent was away, Victor was capably managing his brother's business interests. Prudent had purchased a building on the northeast corner of Aliso and Los Angeles Streets in 1854 for $11,000. Victor spent $25,000 - an absolute fortune at the time - on remodeling and improving the building. In this case, it was money well spent. After the Beaudry Block was improved, it was considered the finest building in Southern California for the time. Rents increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Prudent returned to Los Angeles in 1861 (Victor had been offered a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and found it difficult to manage his brother's business interests at the same time). He continued in the mercantile business until 1865. Due to stress, he retired...but not for long. The Beaudrys just weren't capable of being unproductive.

In 1867, Prudent Beaudry made one of his greatest real estate investments. The steep hill above New High Street, which he purchased at a Sheriff's Department auction for the pittance of $55 (I can't believe it either), was known as Bunker Hill. It would soon become famous for its Victorian mansions.

This purchase set Beaudry on a path that made him California's first realtor and first large-scale developer, in addition to an urban planner. Before long, he was buying extensive tracts of land, dividing them into lots, and selling them, working out of an office opposite the Pico House. One 20-acre tract, between Charity (Grand) and Hill from Second to Fourth, cost $517 and netted $30,000. Another tract, consisting of 39 acres bordered by Fourth, Sixth, Pearl (Figueroa) and Charity (Grand), earned $50,000.

The Beaudry brothers (smartly) kept buying land. They predicted - correctly, and beyond their wildest dreams - that after railroad lines connected Los Angeles to San Francisco and the East Coast, new settlers would pour into Southern California in droves. (If they could only see how right they were!) Prudent also bought land in modern-day Arcadia and near the Sierra Nevada mountains (building aqueducts to redirect mountain streams to his properties), and helped to found the cities of Pasadena and Alhambra.

One newspaper advertisement from 1873 lists 83 (yes, 83!) separate lots for houses, in addition to two full city blocks, multiple city tracts, and large land parcels in Rancho San Pedro, Verdugo Ranch, and the Warner and de la Hortilla land grants. A similar ad from 1874 notes, in bold, which of the streets with lots for sale had already had water pipes installed. It's no wonder Beaudry was able to keep his real estate business going every time he lost most (or all) of his money.

Severe flooding in January 1868 had undone nearly all of Jean-Louis Sainsevain and Damien Marchesseault's hard work on the city's primitive water system. As a developer, Beaudry was very concerned about improving the city for its residents. On July 22, 1868, a 30-year contract for the water system was granted to the newly-established Los Angeles City Water Company. The three partners in the Company were Dr. John Griffin, French-born businessman Solomon Lazard, and, of course, Prudent Beaudry (most of the employees were also of French extraction - chief amongst them, Charles Lepaon, Charles Ducommun, and Eugene Meyer - more on them in the future).

The Los Angeles City Water Company replaced Sainsevain and Marchesseault's leaky wood pipes with 12 miles of iron pipes, and continued to regularly make improvements on the water system until the contract expired 30 years later (the city purchased the system for $2 million - in 1898 dollars!). Although nothing could cancel out the previous water problems or Marchesseault's tragic suicide, the city of Los Angeles finally had a reliable water system that wouldn't turn streets into sinkholes. (If you live in Los Angeles and you like having running water, thank a Frenchman. Seriously, you guys owe us.)

You're probably wondering how Prudent managed to supply water to his hilltop property. In those days, hills weren't desirable places to build homes because water had to be transported in barrels via trolley or other vehicle. The city water company wasn't interested in solving the problem. But in case you haven't noticed yet, Prudent was smart, resourceful, and didn't give up easily. He knew that if running water was available, prospective homeowners would be more likely to consider hilltop lots and pay a good price for them. So he constructed a huge reservoir and a pump system that supplied water from LA's marshy lowlands to Bunker Hill. The pump system worked perfectly - and so did his plan. (I'll bet every land speculator in Southern California wished they had thought of that.)

Before long, Bunker Hill became THE place to build grand homes. At least two of its fabled Victorian mansions were built for other French Angelenos - entrepreneur Pierre Larronde and model citizen Judge Julius Brousseau.

Let it be known, however, that Beaudry developed for everyone. It's true that he built mansions and had a keen interest in architecture, but he also built modest homes on small lots for working families. And because he made modest properties available for small monthly payments, he made home ownership possible for buyers with lower incomes. He made considerable improvements to his land - paving roads, planting trees, and providing for water usage.

And Beaudry just kept developing land for the rest of his life. This Lost LA article includes an 1868 map showing five tracts recently developed by Beaudry.

The Bellevue tract included a garden he dubbed "Bellevue Terrace". This early park rose 70 feet above downtown, boasting hundreds of eucalyptus and citrus trees. Beaudry eventually put the site up for sale. The State of California bought it to develop a Los Angeles campus of the State Normal School, which would later become UCLA. When UCLA moved to Westwood in the 1920s, the hill was graded down and replaced with Central Library.

A few miles away, where North Beaudry Avenue meets Sunset Boulevard, there is an oval-shaped parcel of land that currently holds a church, a restaurant, and The Elysian apartment building. In the early 1870s, this was Beaudry Park - another garden paradise on a hill, boasting citrus groves and eucalyptus trees (and vineyards!). But the Beaudrys put it on the market a decade later. The Sisters of Charity snapped it up in 1883, building a newer facility and relocating St. Vincent's Hospital (sometimes called the Los Angeles Infirmary) here.

Beaudry owned a large tract containing one block of stagnant, foul-smelling marshland. No one wanted to build on the land, and it wasn't ideally suited to building anyway. In 1870, Beaudry got the idea to drain the marsh and turn the land into a public park. Naturally, he spearheaded the plan. Originally called Los Angeles Park, the land was renamed Central Park in the 1890s...and was renamed again later.

You know this park. There's a good chance you've been there (and there's a VERY good chance you absolutely hate its current incarnation).

Give up yet?

It's Pershing Square. (It used to be a very nice park. Trust me on this.)

Beaudry's dedication to developing, planning, and improving the city got him started in politics. He was elected to the Los Angeles Common (City) Council for three one-year terms (1871, 1872, and 1873). In 1873, he became the first president of the city's new Board of Trade. His name appeared in Los Angeles newspapers frequently throughout the 1870s and 1880s - mostly in the real estate sections (and in a bankruptcy case...the Temple and Workman Bank failed and took most of his money with it).

In 1874, Prudent Beaudry became Los Angeles' third French mayor, serving two terms. At the same time, his brother Jean-Louis Beaudry was serving as mayor of Montreal.

After finishing his second term, Beaudry bought the local French-language newspaper, L'Union. (I will cover LA-based French newspapers - three or four are known to have existed - at a later date.) Beaudry was already a director of the Los Angeles City and County Printing and Publishing Company.

Nearly all of Los Angeles' Victorian houses have been torn down over the years. However, neighborhoods like Angelino Heights still have Victorian-era homes. Guess who developed Angelino Heights? That's right - Prudent and Victor Beaudry (architect Joseph Newsom designed many of the houses). Carroll Avenue, beloved by preservationists for its high concentration of surviving Victorian homes (kitsch king Charles Phoenix even includes it on his annual Disneyland-themed DTLA tour as "Main Street USA"), is well within the original boundaries of Angelino Heights.

In the 1880s, Angelino Heights was one of LA's earliest suburbs. Cars would not be commonly used for quite some time. To serve the transit needs of potential home buyers, the Beaudry brothers (with several other real estate promoters) built the Temple Street Cable Railroad. This streetcar ran along Temple Street from Edgeware to Spring (it was soon extended to Hoover Street) every ten minutes and ran for 16 hours each day, making transportation fast and simple for residents of Angelino Heights and Bunker Hill. The Pacific Electric Railway eventually purchased the line (switching from cable cars to electric trolleys in 1902), and in time it passed to the Los Angeles Railway. The Temple Street Cable Railroad - far and away the most successful streetcar line in the city's history - ran from 1886 to 1946. SIXTY YEARS. Which is especially impressive considering the Pacific Electric Railway didn't even exist until 1901, and its less-traveled streetcar lines were converted to bus routes in 1925.

Funnily enough, Beaudry had sued the Los Angeles Railway in 1891. He claimed the Railway had excavated First and Figueroa Streets without the proper authority, rendered the streets useless, and blocked access to his property. (He also occasionally sued people who damaged his properties. Can you blame the guy? Building a city is hard work.)

When "Crazy Remi" Nadeau decided to liquidate most of his freighting company's equipment, it was purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company...which counted Prudent and Victor Beaudry among its shareholders. In the 1880s, the Beaudrys began to take on fewer and fewer projects, but they both remained vocal supporters of developing and improving Los Angeles.

Prudent Beaudry passed away on May 29, 1893, a week after suffering a paralytic stroke (Victor had passed away in 1888, with Prudent acting as executor of his sizable estate). An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County stated:

Prudent Beaudry, in particular, has the record of having made in different lines five large fortunes, four of which, through the act of God, or by the duplicity of man, in whom he had trusted, have been lost; but even then he was not discouraged, but faced the world, even at an advanced age, like a lion at bay, and his reward he now enjoys in the shape of a large and assured fortune. Of such stuff are the men who fill great places, and who develop and make a country. To such men we of this later day owe much of the beauty and comfort that surround us, and to such we should look with admiration as models upon which to form rules of action in trying times.Beaudry died a wealthy man (despite losing his fortune FOUR times), but ironically, he might have died even wealthier. A 1905 article in the Los Angeles Herald stated that nearly forty years previously (i.e. in the 1860s), he had begun to dig a well on one of his hilltop properties. After several hundred feet, he struck a deposit that "looked and smelled like tar." He promptly abandoned the half-dug well. That's right - Beaudry struck oil. But he wasn't looking for oil and had no use for it. Had he made the same discovery a few decades later, things may have been a little different.

The late Mayor's body was returned to his native Quebec. Like the rest of his family, he is buried at Notre Dame des Neiges (Canada's largest, and arguably most beautiful, cemetery). He never married and had no children, so his estate went to the other Beaudry siblings and their families.

Prudent Beaudry's importance as an urban planner and city developer is almost completely forgotten today. His work lingers in the names of Beaudry Avenue, Bellevue Avenue, and various other French-named streets in tracts he developed long ago. (Hill Street was once called Montreal Street in honor of the brothers' hometown - it isn't clear when it was renamed.)

(And, thankfully, Angelino Heights is still standing. I will lose my last remaining shreds of faith in humanity if something bad happens to those precious few surviving Victorians.)

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

The Warren Buffett of Early LA: Mayor Joseph Mascarel

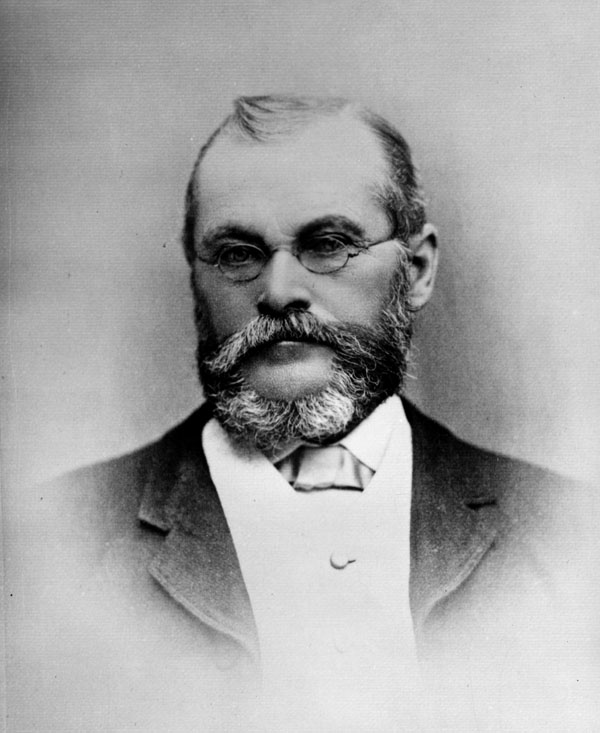

Joseph Mascarel, second French mayor of Los Angeles, on a small information kiosk outside the French Hospital.

Joseph Mascarel was born in the French seaport of Marseille on April 1, 1816. At the tender age of 8 (that's not a typo), he first glimpsed the port of San Pedro while serving as a cabin boy. Legend has it that he swore to one day live in California.

In 1827, 11-year-old Joseph was a cadet on the Jeannette, bound for Hawaii and Tahiti. The Jeannette made a stop in San Pedro, where one of the passengers - Jean-Louis Vignes - did some trading in port before the ship left for Hawaii. (It isn't clear if Vignes and Mascarel became acquainted on this voyage.)

Mascarel continued to sail around the world, working on ships and trading on the side. By 1844, he had saved enough money to buy the Jeannette. Mascarel, now 28 and the ship's captain, sailed his ship back to San Pedro, sold it, and bought an entire city block with the profits. (Specifically, Main to Los Angeles Streets at Commercial Street - on the northern edge of the original Frenchtown.) He also purchased forty acres of farmland in modern-day Hollywood, north of Gower Street, and grew tomatoes. (It's so funny to think of tomato plants growing along Gower Street today.) Mascarel lived in an old adobe house on Main Street for many years, but don't bother looking for it today...the corner where it once stood is now (drumroll please...) a parking lot adjoining Olvera Street. (The sheer number of Frenchtown sites that have since become parking lots is really beginning to depress me. But I digress.)

Mascarel was accompanied by a friend from Marseille - M. Lemontour. In fact, Mascarel had assisted Lemontour with travel expenses. Lemontour worked for Mascarel until he had paid him back, then moved on to Mexico City (Los Angeles, still a small and sleepy pueblo, wasn't as exciting as Lemontour liked). Many years later, Lemontour had become a wealthy Mexican official, and he met up with his old friend Mascarel to catch up and trade stories.

Although there was a growing French community by 1844, the vast majority of Angelenos were Mexican or Spanish. Mascarel - who was one of the few Caucasians to settle in Sonora Town - learned to speak Spanish fluently and was soon dubbed "Don José" by his neighbors. He also became a part owner of Los Angeles' first bakery (Angelenos weren't paranoid about carbs yet). Before too long, he was in the wine industry, got into mining, and distributed lime. A Chatsworth History program states that in 1845, he worked for Jean-Louis Vignes as a cooper.

In spite of his gruff, stern exterior and imposing presence (he was over six feet tall and weighed about 200 pounds - enormous for a Frenchman), Mascarel was a decent and generous man, and became a very popular local figure.

Mascarel got into some trouble in 1847. California was still part of Mexico, and Mascarel was one of a band of volunteer soldiers supporting the United States. The volunteers were captured and detained at Rancho Los Cerritos (i.e. modern-day Long Beach). However, they were in luck: their host was Don Juan Temple, an Anglo settler who had been appointed alcalde (mayor) of Los Angeles by Commodore Stockton. Temple responded by bringing two barrels of wine to Rancho Los Cerritos, plus his family for company, to ease the volunteers' "captivity". Needless to say, a good time was had by all.

The volunteers had to promise not to bear arms against the Californios in order to secure their release. Mascarel and Louis Robidoux (founder of Jurupa/Riverside) decided to obey the letter of their promise rather than its spirit. Robidoux supplied General Frémont's troops with flour from his grist mill, and Mascarel provided vegetables and livestock.

Supporting the United States was a potentially risky endeavor for Mascarel. His new bride, Serilda Lugo, was related to a prominent Californio family - the Alvarados of San Juan Capistrano. (Records disagree on whether Serilda was Native American, Spanish, or mixed race.) I have yet to find any reference to Mascarel having trouble with his in-laws, but the couple got along well enough to have eight children.

In 1853, Mascarel decided to visit France. He took $40,000 with him (about $1.2 million today) and left Serilda behind to manage his business (besides wine, farming, and mining, he was an avid investor and speculator). Mysteriously, Mascarel needed Serilda to send money for his return trip three years later. To this day, no one knows how Mascarel managed to lose such a large amount of money (my best guess would be a bad investment). Fortunately, Serilda was more than capable of managing Mascarel's business interests on her own.

In 1861, Mascarel and a business partner constructed a block of buildings along the south side of Commercial Street between Main and Los Angeles Street. The Mascarel-Barri block, which replaced several crumbling adobe buildings, was divided in 1865.

Another Frenchman, Damien Marchesseault, had served several terms as Mayor. His re-election streak was broken only by Joseph Mascarel, who served as Mayor from 1865-1866.

Mascarel was a very tough mayor. He responded to the city's abysmally high rate of violent crime by banning residents from carrying any weapons whatsoever (even slingshots were prohibited). This wasn't his most popular move (LA was still the Wild West), but Mascarel was often credited with maintaining order in a divided Los Angeles. Although California was a Union state, many of Los Angeles' white inhabitants were Southerners, the city leaned Confederate (read Los Angeles in Civil War Days if you don't believe me), and the Civil War was raging. Keeping the peace with a populace divided over a highly contentious war is quite a task.

Mascarel was held in high esteem by French, Spanish, and Mexican Angelenos. However, the growing Anglo minority took issue with Mascarel's inability to speak English. In fact, the April 23, 1866 edition of the Los Angeles Weekly News included a savage classified ad: "Wanted. A Candidate for Mayor who can read and speak the English language, by Many Citizens." (This may not have been an entirely fair demand, considering that the vast majority of Angelenos were native Spanish speakers, French was the second most common language, and English would remain a distant third for some time.)

Still, Mascarel's political career wasn't quite over. He was popular enough to be elected to the City Council seven times between 1867 and 1881. In later years, he would lend support to others who ran for office.

While serving as Mayor, Mascarel signed a significant land grant to the Pioneer Oil Company, the first of Southern California's many oil companies. (One of Pioneer's organizers was Charles Ducommun, a Francophone Swiss watchmaker we'll meet again later.)

According to an account by Horace Bell, Mascarel quietly kept a close eye on Mayor Joel Turner and the City Council. He dutifully reported their corrupt dealings, which included interfering with the water system, to the Grand Jury, which promptly indicted Turner and the councilmen. Turner was sentenced to ten years in prison. He never served a day of his sentence (can't win them all), but control over the Los Angeles River was taken out of the Mayor's hands and given back to the water commissioners. (Good thing, too - in those days, Angelenos were still raising crops and livestock. The city could easily have lost most of its food sources.)

In 1871, Mascarel helped to found the Farmers' and Merchants' Bank, serving as one of its trustees (by this time, the city directory listed his occupation as "capitalist"). According to an old newspaper obituary for one of Mascarel's granddaughters, he owned a cannon (courtesy of the Mexican-American War) and placed it at the corner where the first Farmers' and Merchants' Bank originally stood. This cannon was later moved to Exposition Park.

Serilda Lugo Mascarel passed away in 1887. Mascarel and his family soon took out an ad in the newspaper thanking their friends and acquaintances for their kindness and support.

It isn't clear when Joseph Mascarel met his second wife, Maria Jesus Benita Feliz. Nor is it clear when they moved in together and began their common-law marriage. But we do know that they didn't legally marry until 1896 (Mascarel's children with Serilda vocally opposed the marriage and son-in-law J. P. Goytino successfully blocked issuance of a marriage license). Maria had been very ill, and the belated marriage ceremony was carried out in the Catholic Church (a license was not necessary in this case). A Los Angeles Times article published just two days later stated that the 80-year-old former mayor and his 60-year-old bride had been "for all intents and purposes" living as a married couple for thirty years and had several adult children. This very likely means that Joseph and Serilda chose to separate in or before 1866. (Believe it or not, there was a time when divorce was rare in LA.) The 1870 federal census indicates that Serilda and her seven surviving children were no longer living with Joseph.

I should note that Mascarel was one of the wealthiest men in Los Angeles at the time. In spite of his penchant for quietly donating large sums of money to charitable causes, he was worth over a million dollars (and in 1896, that was a LOT of money). The Times noted that Goytino opposed the marriage due to concerns over inheritance of property. (In some ways, LA hasn't changed all that much.)

Joseph Mascarel died of heart failure on October 6, 1899, at his home on Lazard (now Ducommun) Street. He was 83 years old. Mascarel left behind Maria, children from both wives, grandchildren from his first marriage, and the remainder of his fortune. (The bulk of this money was willed to Mascarel's grandchildren from his marriage to Serilda. Maria's children promptly contested the will.) Mascarel had owned land in four counties, but began to give it away to to friends and loved ones in his later years. A solemn high mass was held at the Old Plaza Church in his honor.

Joseph Mascarel is buried at Calvary Cemetery. His headstone lists his first name as "José". The headstone is otherwise in English - ironic, given that he neither spoke nor read the language.

A Los Angeles Daily Herald article from 1889 states "Everybody knows who Jose Mascarel is, as as he lacks but little of being one of the oldest settlers of this city." Today, he has faded from LA's collective memory. A street was named for the former mayor and investor, but it is misspelled as "Mascarell Street."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)