Every Angeleno knows William Mulholland is credited with bringing water to Los Angeles.

Few, if any, are aware that for about forty years, French and French-Canadian Angelenos fought hard to bring safer and more reliable water to the growing city.

Some of those battles ended in muddy sinkholes. One of them ended in a scandalous death. And one of them ultimately prevailed, successfully creating the forerunner for the modern-day Department of Water and Power. (And they managed to do it without stealing water from struggling Native American farmers. Just saying.)

Join me on Sunday, August 2, at noon to learn about these remarkable Angelenos and their efforts - successful and not - to provide water to the City of Angels. Tickets are affordably priced at just $5.

Tales from Los Angeles’ lost French quarter and Southern California’s forgotten French community.

Showing posts with label Los Angeles City Water Company. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Los Angeles City Water Company. Show all posts

Friday, July 17, 2020

Monday, April 9, 2018

The Most Trusted Citizen in 1850s LA was a Jewish Frenchman

|

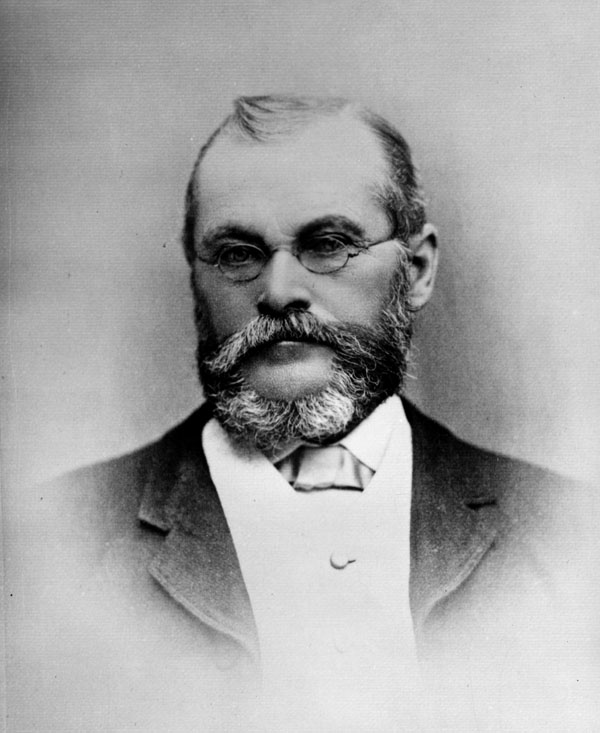

| Don Solomon Lazard |

Imagine, for a moment, that it's the 1850s and you've just arrived in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles has only been part of the United States for a few years (and some would argue it's part of the US in name only). Theft and murder are common. There are no banks (yet). You're carrying a few pieces of jewelry and just enough money to rent a room and start a small business. The ship to San Pedro and the long ride into town weren't cheap, and you can't afford to get robbed.

Who can you trust?

If you asked law-abiding locals who they would trust with cash and valuables, the answer would probably be "Don Solomon".

Solomon Lazard was from Lorraine. After stints in New Orleans and San Francisco working for his cousins' business, Lazard Frères (which was a dry goods company at the time), he decided to open his own dry goods business in San Diego. Unfortunately, sleepy little San Diego was too small of a town to support even a modest shop. Following the advice of a well-traveled sailor, Lazard decided to move his store to Los Angeles.

By 1853, Lazard and his cousin Maurice Kremer had set up shop in Mellus' Row, near the western corner of Los Angeles and Aliso Streets. Aliso Street was a very active business district in the 1850s, and the two cousins also benefitted from residents of San Gabriel, El Monte, and San Bernardino taking Aliso Street into town.

Soon enough, Lazard was elected to the City Council. He was a Third Lieutenant in the Los Angeles Guards (a volunteer militia - Los Angeles didn't have a military base yet). Lazard served on the Committee on Police, Committee on Streets, Committee on Lands, the Library Association, and the Chamber of Commerce. In 1856, he served on the Grand Jury. Two years later, he was appointed to supervise the local election.

Lazard was active in the Hebrew Benevolent Society, heading the Society's Committee on Charity and eventually serving as its President. (The Hebrew Benevolent Society is now known as Jewish Family Service of Los Angeles.) When a deadly smallpox outbreak swept through Los Angeles in 1863 - disproportionately affecting Mexican and Native American Angelenos - the Committee on Charity, under Lazard's leadership, donated $150 (about $2900 today) and collected additional funds to help care for indigent patients.

Early LA didn't really have banks. The town was too lawless to appeal to most bankers, even when business was booming. But locals needed safe places to store money and valuables.

Lazard and Kremer were merchants, not bankers. But they had spotless reputations and a large safe. It didn't take long for their customers to ask if they could leave their gold and silver with Lazard and Kremer for safekeeping. Lazard later partnered with Timothy Wolfskill in a general store. A few years later, Solomon's brother Abraham came to Los Angeles and joined the family business.

Harris Newmark relates a story about Lazard's professional ethics: Austrian immigrant Mathias "Mateo" Sabichi had left $30,000 with Lazard. No one had heard from Sabichi in so long that Lazard's employees thought he would never come for it. But Sabichi eventually returned to town, and upon presenting the certificate of deposit, was able to claim every cent.

It's hardly surprising that Lazard was known as "Don Solomon". He was such a popular local figure that he often floor-managed balls and fandangos and served as pallbearer for at least one local industrialist's funeral.

Towards the end of 1860, Lazard was arrested in his native France. He had returned home to visit his mother, and, as French law dictated, had registered with the local police. Young French men were legally required to complete a term of military service, and Lazard had left home at age seventeen without having done so. In spite of the fact that he was now a U.S. citizen, Lazard was court-martialed and sentenced to a stint in prison.

Lazard was in luck, however: the newly-appointed American minister to France, Charles J. Faulkner, worked to secure his release, and Emperor Napoleon III intervened. (Ironically, Faulkner - a Southerner who was arrested in early 1861 for trying to secure weapons for the Confederacy - was the author of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.) Lazard did have to pay a fine, but he was able to return to Los Angeles in early 1861.

A street in the heart of Frenchtown was named Lazard Street. It was later changed to Ducommun Street (Ducommun Yard, home base for Ducommun Industries, was bordered by the street on one side - the site is now a Little Tokyo bus depot). A different Lazard Street exists today - it's a short residential cul-de-sac in San Fernando. (Side note: I was pleasantly surprised to see Cinderella Ranch houses on Lazard Street. I am obsessed with them.) Mayor Joseph Mascarel lived at 99 Lazard Street (the old one downtown) during the last years of his life.

|

| Lazard Street sign in San Fernando |

Lazard's store - which sold French, English, and American-made dry goods, boots, shoes, clothing, and groceries (boasting in an 1852 newspaper advertisement that they would always sell goods at the lowest market prices for cash and pay the highest price for gold dust) - prospered to the point of becoming LA's earliest department store. City of Paris was a fixture of downtown Los Angeles and the city's French community for years.

As time marched on, LA got bigger, and water management got to be a bigger problem. Marchesseault and Sainsevain weren't successful, but the Los Angeles City Water Company - founded by Prudent Beaudry, Solomon Lazard, and Dr. John S. Griffin - prevailed. Although Beaudry is known for his work as a developer and his successful efforts to bring water to his hilltop properties, he didn't helm the City Water Company. It was Solomon Lazard who held the office of President. When the Company's 30-year lease expired, the city bought the City Water Company - now the Department of Water and Power - for $2 million. (That's about $60 million today.) The water contract specified, among other points, that the Company would replace all the wooden pipes with twelve miles of iron pipes, erect an ornamental fountain in the Plaza (replacing the ugly old reservoir tank that stood on the site), place a fire hydrant at each intersection, and provide water free of charge to public schools, city hospitals, and jails.

Don Solomon, described as an "old pioneer" when he passed away in 1916 at the ripe old age of 89, was survived by his wife and four of their six children. He is buried at Home of Peace Memorial Park in East Los Angeles.

As for his extended family's dry-goods firm, Lazard Frères got into banking after Solomon left. The company is now a publicly-traded investment bank known simply as Lazard (NYSE: LAZ). Some sources (including my copy of Le Guide Francais) credit Solomon with founding Lazard Frères; however, Lazard states that their Los Angeles branch didn't open until 2003. Oddly, a 1987 Los Angeles Times article points to a planned LA office opening soon, claiming it would be the firm's first office in California since the San Francisco branch closed in 1906.

(Edited to add: I originally planned to write about J.B. Leonis this week. In light of the fact that 85-year-old Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll was brutally murdered in her apartment in Paris recently, I put J.B. on the back burner. LA's French community was not a monoculture, and this Franco-American blogger values the Lazards, Kremers, Meyers, Loebs etc. just as much as the Beaudrys, Pellissiers, Brousseaus, Mesmers, etc. Although I am not Jewish, I am from a heavily Jewish neighborhood, and bigotry of any kind really. pisses. me. off.

Rant over. I'm going to bed.)

Monday, January 1, 2018

Excerpts from "Frenchtown! The Musical": Part 2

If you read my first installment of this theatrical theme, you know there isn't *really* a musical about Frenchtown. My short-term objective is to write a book, my long-term objective is a museum. But who knows, the process may make a playwright out of me yet...

(The curtain opens on a stage split between two different locations and two different years.

Stage Right, a marquee reads "City Hall, 1867." The scene is Mayor Damien Marchesseault's office.

Stage Left, a marquee reads "Marchesseault Street, 1868." The scene is a brick office building.

Damien Marchesseault and Jean-Louis Sainsevain enter, stage right. Sainsevain is carrying rolled-up technical drawings.

Prudent Beaudry, Solomon Lazard, and Dr. Griffin enter, stage left. Beaudry is carrying a notebook, Griffin is carrying a few medical texts.

Marchesseault (spoken): Sainsevain, if anyone in Los Angeles is up to the task, it's you.

Sainsevain (spoken): I tried four years ago, Mayor. I could use some help.

Beaudry (spoken): Gentlemen, Marchesseault tried.

Lazard and Griffin (spoken, removing their hats): Poor Marchesseault.

Song: Water!

Marchesseault (sung): This town needs water.

Sainsevain (sung): We're parched.

Marchesseault: The zanjas just don't cut it.

Sainsevain: No one likes a filthy ditch.

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry (sung): This town needs water.

Lazard (sung): Fresh, clean water.

Beaudry: No more mud and garbage.

Griffin: Clean and safe and sanitary.

Beaudry, Lazard, and Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: Dryden's water wheel was a start.

Sainsevain: The judge wasn't thinking big enough.

Marchesseault: You're an engineer.

Sainsevain: You want a new one? But of course!

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: Let's keep the reservoirs to start.

Lazard: We'll need those during drought years.

Beaudry: Keep them close to town (spoken) but not on prime real estate.

Griffin: Lined with bricks to keep the dirt out.

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: We need pipes!

Sainsevain: We can't get pipes! We're too remote!

Marchesseault: We'll make our own.

Sainsevain: From what, the sycamores outside?!

Marchesseault (spoken): That's it!

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: Our predecessors meant well but they couldn't cut the mustard

Lazard: Beaudry, it was a disaster

Beaudry: Never send a politician to do a businessman's job

Griffin: Or a doctor's!

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: We've got trouble, Sainsevain

Sainsevain: Another sinkhole? Damn it!

Marchesseault: Downtown is a muddy mess

Sainsevain: Did I become an engineer for this?

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: The world is watching, gentlemen

Lazard: We've got to get it right

Beaudry: It's a 30-year contract

Griffin: But everyone expects results

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: I've borrowed from everyone I know

Beaudry: We're on the right track, gentlemen

Sainsevain: I'm about to lose the vineyard

Lazard: Together we can make it work

Marchesseault, Sainsevain, Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin (in unison): Los Angeles needs water!

(The curtain opens on a stage split between two different locations and two different years.

Stage Right, a marquee reads "City Hall, 1867." The scene is Mayor Damien Marchesseault's office.

Stage Left, a marquee reads "Marchesseault Street, 1868." The scene is a brick office building.

Damien Marchesseault and Jean-Louis Sainsevain enter, stage right. Sainsevain is carrying rolled-up technical drawings.

Prudent Beaudry, Solomon Lazard, and Dr. Griffin enter, stage left. Beaudry is carrying a notebook, Griffin is carrying a few medical texts.

Marchesseault (spoken): Sainsevain, if anyone in Los Angeles is up to the task, it's you.

Sainsevain (spoken): I tried four years ago, Mayor. I could use some help.

Beaudry (spoken): Gentlemen, Marchesseault tried.

Lazard and Griffin (spoken, removing their hats): Poor Marchesseault.

Song: Water!

Marchesseault (sung): This town needs water.

Sainsevain (sung): We're parched.

Marchesseault: The zanjas just don't cut it.

Sainsevain: No one likes a filthy ditch.

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry (sung): This town needs water.

Lazard (sung): Fresh, clean water.

Beaudry: No more mud and garbage.

Griffin: Clean and safe and sanitary.

Beaudry, Lazard, and Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: Dryden's water wheel was a start.

Sainsevain: The judge wasn't thinking big enough.

Marchesseault: You're an engineer.

Sainsevain: You want a new one? But of course!

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: Let's keep the reservoirs to start.

Lazard: We'll need those during drought years.

Beaudry: Keep them close to town (spoken) but not on prime real estate.

Griffin: Lined with bricks to keep the dirt out.

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: We need pipes!

Sainsevain: We can't get pipes! We're too remote!

Marchesseault: We'll make our own.

Sainsevain: From what, the sycamores outside?!

Marchesseault (spoken): That's it!

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: Our predecessors meant well but they couldn't cut the mustard

Lazard: Beaudry, it was a disaster

Beaudry: Never send a politician to do a businessman's job

Griffin: Or a doctor's!

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: We've got trouble, Sainsevain

Sainsevain: Another sinkhole? Damn it!

Marchesseault: Downtown is a muddy mess

Sainsevain: Did I become an engineer for this?

Marchesseault and Sainsevain: We need water!

Beaudry: The world is watching, gentlemen

Lazard: We've got to get it right

Beaudry: It's a 30-year contract

Griffin: But everyone expects results

Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin: We need water!

Marchesseault: I've borrowed from everyone I know

Beaudry: We're on the right track, gentlemen

Sainsevain: I'm about to lose the vineyard

Lazard: Together we can make it work

Marchesseault, Sainsevain, Beaudry, Lazard, Griffin (in unison): Los Angeles needs water!

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

He Built This City: Mayor Prudent Beaudry

Possessing boundless energy, exceptional business sagacity and foresight, Prudent Beaudry amassed five fortunes and lost four in his ventures, which were gigantic for that time, and would be considered immense today.

Have a seat, everyone...the lifetime I'm chronicling this week is best described as "epic".

Jean-Prudent Beaudry was born July 24, 1816 in Mascouche, Quebec - close to Montreal. When he was a young boy, the family moved to the neighboring town of Saint-Anne-des-Plaines.

There were five Beaudry brothers (and three Beaudry sisters). All of the Beaudry brothers worked hard and got rich, but Prudent, Jean-Louis, and Victor would make the history books. (Victor, the only other Beaudry to settle in Los Angeles, will be covered in another entry, because this one is going to be LONG.)

The Beaudrys, an industrious family of traders, sent their sons to good schools in Montreal and New York. Prudent and his brothers had the benefits of a great education and English fluency when they went into business for themselves.

Which they did, many times over.

Prudent started out in his father's mercantile business, then went to work at a different mercantile house in New Orleans, returning to Canada in 1842 to partner with one of his brothers. By 1844, he left the business to join Victor, the youngest Beaudry brother, in San Francisco. The Gold Rush was a few years away, but Victor had already established a profitable shipping and commission business in the city. Before long, the brothers were in the ice business (Victor later partnered with another future mayor, Damien Marchesseault, in distributing ice harvested in the San Bernardino Mountains). Perhaps not surprisingly for a native of Quebec, Prudent also got into the syrup business. Two years later, after Prudent had lost most of his money on real estate speculation (and more of it when insufficiently insured stock was destroyed in a fire), Los Angeles beckoned.

I'll let Le Guide Francais take it from here:

Starting with $1,100 in goods and $200 cash in a small store on Main Street, where the City Hall now stands, it is said that he cleared $2,000 in thirty days, which enabled him to take a larger store on Commercial Street. From that time on, Prudent Beaudry was one of the preeminent men of the economic, social, and political life of the Southwest.(The book, just to clarify, refers to the current City Hall, not the old Bell Block down the street. After Beaudry vacated the Commercial Street shop, Harris Newmark moved in. Ironically, Beaudry sold his dry goods business to Newmark twelve years later.)

Having earned a well-deserved vacation, Prudent left Los Angeles for Paris in 1855. The chief items on his itinerary were seeing the Exposition Universelle and consulting the great French oculist Dr. Jules Sichel. Prudent visited Montreal on his return trip to visit his brother Jean-Louis, who would serve as Mayor of Montreal for a total of ten years between 1862 and 1885. The Beaudrys, needless to say, were just as prominent in business, politics, and society in Quebec as they were in Southern California.

While Prudent was away, Victor was capably managing his brother's business interests. Prudent had purchased a building on the northeast corner of Aliso and Los Angeles Streets in 1854 for $11,000. Victor spent $25,000 - an absolute fortune at the time - on remodeling and improving the building. In this case, it was money well spent. After the Beaudry Block was improved, it was considered the finest building in Southern California for the time. Rents increased from $300 per month to $1,000 per month.

Prudent returned to Los Angeles in 1861 (Victor had been offered a contract to supply the Army of the Potomac and found it difficult to manage his brother's business interests at the same time). He continued in the mercantile business until 1865. Due to stress, he retired...but not for long. The Beaudrys just weren't capable of being unproductive.

In 1867, Prudent Beaudry made one of his greatest real estate investments. The steep hill above New High Street, which he purchased at a Sheriff's Department auction for the pittance of $55 (I can't believe it either), was known as Bunker Hill. It would soon become famous for its Victorian mansions.

This purchase set Beaudry on a path that made him California's first realtor and first large-scale developer, in addition to an urban planner. Before long, he was buying extensive tracts of land, dividing them into lots, and selling them, working out of an office opposite the Pico House. One 20-acre tract, between Charity (Grand) and Hill from Second to Fourth, cost $517 and netted $30,000. Another tract, consisting of 39 acres bordered by Fourth, Sixth, Pearl (Figueroa) and Charity (Grand), earned $50,000.

The Beaudry brothers (smartly) kept buying land. They predicted - correctly, and beyond their wildest dreams - that after railroad lines connected Los Angeles to San Francisco and the East Coast, new settlers would pour into Southern California in droves. (If they could only see how right they were!) Prudent also bought land in modern-day Arcadia and near the Sierra Nevada mountains (building aqueducts to redirect mountain streams to his properties), and helped to found the cities of Pasadena and Alhambra.

One newspaper advertisement from 1873 lists 83 (yes, 83!) separate lots for houses, in addition to two full city blocks, multiple city tracts, and large land parcels in Rancho San Pedro, Verdugo Ranch, and the Warner and de la Hortilla land grants. A similar ad from 1874 notes, in bold, which of the streets with lots for sale had already had water pipes installed. It's no wonder Beaudry was able to keep his real estate business going every time he lost most (or all) of his money.

Severe flooding in January 1868 had undone nearly all of Jean-Louis Sainsevain and Damien Marchesseault's hard work on the city's primitive water system. As a developer, Beaudry was very concerned about improving the city for its residents. On July 22, 1868, a 30-year contract for the water system was granted to the newly-established Los Angeles City Water Company. The three partners in the Company were Dr. John Griffin, French-born businessman Solomon Lazard, and, of course, Prudent Beaudry (most of the employees were also of French extraction - chief amongst them, Charles Lepaon, Charles Ducommun, and Eugene Meyer - more on them in the future).

The Los Angeles City Water Company replaced Sainsevain and Marchesseault's leaky wood pipes with 12 miles of iron pipes, and continued to regularly make improvements on the water system until the contract expired 30 years later (the city purchased the system for $2 million - in 1898 dollars!). Although nothing could cancel out the previous water problems or Marchesseault's tragic suicide, the city of Los Angeles finally had a reliable water system that wouldn't turn streets into sinkholes. (If you live in Los Angeles and you like having running water, thank a Frenchman. Seriously, you guys owe us.)

You're probably wondering how Prudent managed to supply water to his hilltop property. In those days, hills weren't desirable places to build homes because water had to be transported in barrels via trolley or other vehicle. The city water company wasn't interested in solving the problem. But in case you haven't noticed yet, Prudent was smart, resourceful, and didn't give up easily. He knew that if running water was available, prospective homeowners would be more likely to consider hilltop lots and pay a good price for them. So he constructed a huge reservoir and a pump system that supplied water from LA's marshy lowlands to Bunker Hill. The pump system worked perfectly - and so did his plan. (I'll bet every land speculator in Southern California wished they had thought of that.)

Before long, Bunker Hill became THE place to build grand homes. At least two of its fabled Victorian mansions were built for other French Angelenos - entrepreneur Pierre Larronde and model citizen Judge Julius Brousseau.

Let it be known, however, that Beaudry developed for everyone. It's true that he built mansions and had a keen interest in architecture, but he also built modest homes on small lots for working families. And because he made modest properties available for small monthly payments, he made home ownership possible for buyers with lower incomes. He made considerable improvements to his land - paving roads, planting trees, and providing for water usage.

And Beaudry just kept developing land for the rest of his life. This Lost LA article includes an 1868 map showing five tracts recently developed by Beaudry.

The Bellevue tract included a garden he dubbed "Bellevue Terrace". This early park rose 70 feet above downtown, boasting hundreds of eucalyptus and citrus trees. Beaudry eventually put the site up for sale. The State of California bought it to develop a Los Angeles campus of the State Normal School, which would later become UCLA. When UCLA moved to Westwood in the 1920s, the hill was graded down and replaced with Central Library.

A few miles away, where North Beaudry Avenue meets Sunset Boulevard, there is an oval-shaped parcel of land that currently holds a church, a restaurant, and The Elysian apartment building. In the early 1870s, this was Beaudry Park - another garden paradise on a hill, boasting citrus groves and eucalyptus trees (and vineyards!). But the Beaudrys put it on the market a decade later. The Sisters of Charity snapped it up in 1883, building a newer facility and relocating St. Vincent's Hospital (sometimes called the Los Angeles Infirmary) here.

Beaudry owned a large tract containing one block of stagnant, foul-smelling marshland. No one wanted to build on the land, and it wasn't ideally suited to building anyway. In 1870, Beaudry got the idea to drain the marsh and turn the land into a public park. Naturally, he spearheaded the plan. Originally called Los Angeles Park, the land was renamed Central Park in the 1890s...and was renamed again later.

You know this park. There's a good chance you've been there (and there's a VERY good chance you absolutely hate its current incarnation).

Give up yet?

It's Pershing Square. (It used to be a very nice park. Trust me on this.)

Beaudry's dedication to developing, planning, and improving the city got him started in politics. He was elected to the Los Angeles Common (City) Council for three one-year terms (1871, 1872, and 1873). In 1873, he became the first president of the city's new Board of Trade. His name appeared in Los Angeles newspapers frequently throughout the 1870s and 1880s - mostly in the real estate sections (and in a bankruptcy case...the Temple and Workman Bank failed and took most of his money with it).

In 1874, Prudent Beaudry became Los Angeles' third French mayor, serving two terms. At the same time, his brother Jean-Louis Beaudry was serving as mayor of Montreal.

After finishing his second term, Beaudry bought the local French-language newspaper, L'Union. (I will cover LA-based French newspapers - three or four are known to have existed - at a later date.) Beaudry was already a director of the Los Angeles City and County Printing and Publishing Company.

Nearly all of Los Angeles' Victorian houses have been torn down over the years. However, neighborhoods like Angelino Heights still have Victorian-era homes. Guess who developed Angelino Heights? That's right - Prudent and Victor Beaudry (architect Joseph Newsom designed many of the houses). Carroll Avenue, beloved by preservationists for its high concentration of surviving Victorian homes (kitsch king Charles Phoenix even includes it on his annual Disneyland-themed DTLA tour as "Main Street USA"), is well within the original boundaries of Angelino Heights.

In the 1880s, Angelino Heights was one of LA's earliest suburbs. Cars would not be commonly used for quite some time. To serve the transit needs of potential home buyers, the Beaudry brothers (with several other real estate promoters) built the Temple Street Cable Railroad. This streetcar ran along Temple Street from Edgeware to Spring (it was soon extended to Hoover Street) every ten minutes and ran for 16 hours each day, making transportation fast and simple for residents of Angelino Heights and Bunker Hill. The Pacific Electric Railway eventually purchased the line (switching from cable cars to electric trolleys in 1902), and in time it passed to the Los Angeles Railway. The Temple Street Cable Railroad - far and away the most successful streetcar line in the city's history - ran from 1886 to 1946. SIXTY YEARS. Which is especially impressive considering the Pacific Electric Railway didn't even exist until 1901, and its less-traveled streetcar lines were converted to bus routes in 1925.

Funnily enough, Beaudry had sued the Los Angeles Railway in 1891. He claimed the Railway had excavated First and Figueroa Streets without the proper authority, rendered the streets useless, and blocked access to his property. (He also occasionally sued people who damaged his properties. Can you blame the guy? Building a city is hard work.)

When "Crazy Remi" Nadeau decided to liquidate most of his freighting company's equipment, it was purchased by the Oro Grande Mining Company...which counted Prudent and Victor Beaudry among its shareholders. In the 1880s, the Beaudrys began to take on fewer and fewer projects, but they both remained vocal supporters of developing and improving Los Angeles.

Prudent Beaudry passed away on May 29, 1893, a week after suffering a paralytic stroke (Victor had passed away in 1888, with Prudent acting as executor of his sizable estate). An Illustrated History of Los Angeles County stated:

Prudent Beaudry, in particular, has the record of having made in different lines five large fortunes, four of which, through the act of God, or by the duplicity of man, in whom he had trusted, have been lost; but even then he was not discouraged, but faced the world, even at an advanced age, like a lion at bay, and his reward he now enjoys in the shape of a large and assured fortune. Of such stuff are the men who fill great places, and who develop and make a country. To such men we of this later day owe much of the beauty and comfort that surround us, and to such we should look with admiration as models upon which to form rules of action in trying times.Beaudry died a wealthy man (despite losing his fortune FOUR times), but ironically, he might have died even wealthier. A 1905 article in the Los Angeles Herald stated that nearly forty years previously (i.e. in the 1860s), he had begun to dig a well on one of his hilltop properties. After several hundred feet, he struck a deposit that "looked and smelled like tar." He promptly abandoned the half-dug well. That's right - Beaudry struck oil. But he wasn't looking for oil and had no use for it. Had he made the same discovery a few decades later, things may have been a little different.

The late Mayor's body was returned to his native Quebec. Like the rest of his family, he is buried at Notre Dame des Neiges (Canada's largest, and arguably most beautiful, cemetery). He never married and had no children, so his estate went to the other Beaudry siblings and their families.

Prudent Beaudry's importance as an urban planner and city developer is almost completely forgotten today. His work lingers in the names of Beaudry Avenue, Bellevue Avenue, and various other French-named streets in tracts he developed long ago. (Hill Street was once called Montreal Street in honor of the brothers' hometown - it isn't clear when it was renamed.)

(And, thankfully, Angelino Heights is still standing. I will lose my last remaining shreds of faith in humanity if something bad happens to those precious few surviving Victorians.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)