Georges Le Mesnager arrived in California in 1867. He was sixteen years old.

In July of 1870, the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Travel time and expenses be damned, nineteen-year-old Georges immediately packed up and went back to France to enlist in the French Army and defend his homeland under General de Chanzy.

Georges returned to LA after the war ended, and became a U.S. citizen at age 21. He worked as a notary and court translator (remember, French was more commonly spoken than English in 1870s LA), owned a store on Commercial Street, and owned property at 1660 N. Main Street.

Georges married Concepción Olarra (sometimes styled "O'Lara"). It isn't clear whether she was Mexican, Spanish, or born in the New World to Spanish parents - and it's possible she had Irish ancestry. Unfortunately I cannot find any records of her birth or death. Records on Ancestry do show other Olarras (none of whom I could conclusively tie to Concepción) living in 19th century Mexico.

Letters published in

La Crónica between 1876-1878 indicate that Concepción was probably a native Spanish speaker. This would not have been a deterrent to the multilingual Georges. They had four children: Louis, George, Louise, and Jeanne.

Georges' intelligence and linguistic abilities served him well when he became the editor of the weekly French-language newspaper

Le Progres, founded in 1883 and headquartered on New High Street.

Le Progrés was politically independent and so popular with Francophone readers (in spite of strong competition from

L'Union Nouvelle) that copies of the newspaper trickled back to France. At least one other French Angeleno, Felix Violé, was inspired to move to Los Angeles after reading a copy of

Le Progrés at the home of a relative with friends in California (but we'll get to the Violé family later).

Like so many of his countrymen in Southern California, Georges got into wine and liquor production. In fact, Georges soon had to give up editing

Le Progrés because his wine business kept him too busy. His grapes were eventually grown in Glendale, but his Hermitage Winery stood at 207 N. Los Angeles Street, close to the heart of Frenchtown. (And now the site is the unattractive Los Angeles Mall. Doesn't seem like a fair trade, does it?)

He was acting president of the Légion Français for three years, but stepped down in 1895 (he was given the title of honorary president as a token of the Légion's gratitude).

In 1894, at the age of 43, Georges married Marie du Creyd Bremond. Marie was 32 and a fellow French immigrant. They had one child together: Evon.

Georges' real estate holdings had their own challenges. In 1896, he sued the city over a dispute regarding streets in the Mesnager housing tract. Two years later, he was threatened by a trigger-happy tenant, Emil Rombaud, and asked for police protection. The same year, the Le Mesnagers sued a different tenant for damaging a rented vineyard. And Georges' more unusual land holdings included partial ownership of the Ventura County islands of San Nicolas and Anacapa. (If you read

Island of the Blue Dolphins in fourth grade, it's a fictionalized account of San Nicolas' last Native American inhabitant, Juana Maria.)

Georges bought a huge parcel of land in what is now Glendale, built a stone barn, and planted grapevines. These days, Deukmejian Wilderness Park preserves the land where the Le Mesnagers grew those grapes.

When Georges' stone barn was damaged by a fire and a flood, his son Louis converted it into a farmhouse.

The Le Mesnager family lived in the stone house until 1968.

Georges was so well acquainted with "King of Calabasas" Miguel Leonis that he was one of two executors of Leonis' estate. (Georges made wine and liquor. Leonis liked to drink. What a coincidence.)

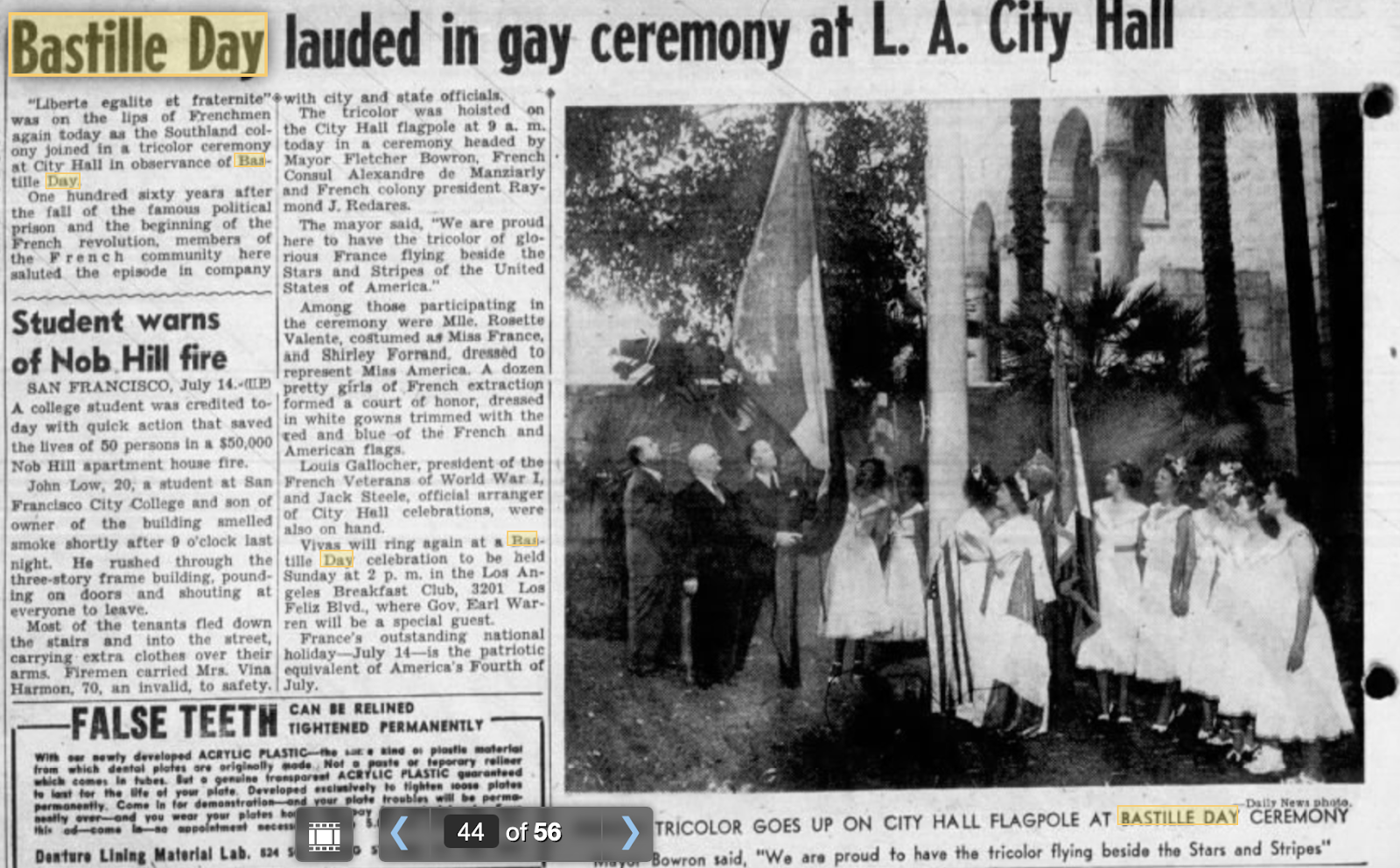

The French community held a huge celebration of Bastille Day's centennial on July 14, 1889. Georges Le Mesnager delivered a speech in French at the event.

On September 21, 1892, the French community

celebrated the centennial of the French Republic. The celebration - even bigger and more spectacular than Bastille Day's centennial three years earlier - featured Georges as the French-language speaker of the day (this being multicultural LA, someone else gave a speech in English). According to

Le Guide Français, published forty years later, "his eloquent and fiery speech still rings in the ears of the older members of the colony."

World War One broke out in 1914. Georges didn't hesitate to return to France and re-enlist in the French Army.

He was 64 years old at the time.

Georges didn't even try to negotiate this with his family. It was too important to him. He simply told his oldest son, "Well, my dear Louis, I am leaving for the war. France needs every one of her sons."

Louis objected, "But you are too old to fight."

Georges didn't care. "I promised in 1870 to be there if France were invaded again, and I want to keep my promise."

Georges sent Marie to visit their daughter Louise in Catalina for a week. He asked their youngest daughter, Evon, to gently break the news to her mother when she returned. Marie was very upset, but reasoned "maybe it is all for the best" in a letter to Georges.

So, Georges traveled to New York and set sail for France. As soon as he arrived, he re-enlisted as a private and was assigned to the 106th Infantry.

It wasn't an easy task. French authorities were highly suspicious of anyone entering the country during wartime, and Georges was detained by police at the dock. According to the

Ocala Evening Star, a gendarme laughed at his plan to rejoin the army. Georges simply reached into his pocket and took out his prized

Legion d'honneur medal - the highest military or civilian honor a French citizen can receive.

"I came from America in 1870 and fought for France and they gave me this. I've come back to fight again."

With the Germans rapidly approaching Paris, soldiers were desperately needed. This was not the time to quibble over a willing volunteer's age. The gendarme kindly directed him to a recruiting station down the street.

The recruiter was hesitant. A 64-year-old private in the infantry was pretty much unheard of. But Georges showed the recruiter his

Legion d'honneur medal, and he was on a troop train that very night.

After just seven days on the front, Georges was shot through the arm and hospitalized for a month. He was quickly promoted to sergeant for gallant conduct.

Georges spent months in the trenches at the seemingly endless battle of Verdun. One day, the unthinkable happened: the 106th ran dangerously low on ammunition.

The colonel asked for a volunteer to retrieve more ammunition. It was a suicide mission. But Georges volunteered, and in spite of the German army's best attempts to shoot him down, succeeded. For his courage, he was given the

croix de guerre. The colonel told his regiment "Every soldier should have the courage and spirit of this veteran comrade."

One night, Georges was talking to his regimental adjutant when a German artillery shell passed between them, landed nearby, and exploded.

Both men survived, although the explosion sent them flying. Georges regained consciousness under a tree, retrieved parts of the spent artillery shell, brought them back to the trench, and showed them to his troops.

"It was nothing at all, nothing at all," he laughed. "Don't ever be afraid of a shell like this one. It's only the shell that hits you that you need to dread."

The colonel overheard this remark, and recommended Georges for further honors. He received another medal, the

palme.

In a later battle, a massive German soldier tried to take out the aging Georges - who ran him through. For this, he received yet another medal, this one for bravery in hand-to-hand combat.

Georges' courage in the battles of Eparges, Chemin des Dames, and the trancheé de Calonne did not escape notice, and he was wounded five times during the war.

Georges' family knew nothing of this until Marie read about his heroics in a book published after the war's end. She told the

Tonopah Daily Bonanza "It is characteristic of my husband that he should say nothing of being wounded. He never writes anything about himself. It is always about the bravery of others. The only information of personal nature I had from him was that his weight had decreased, but he always insisted he was well. He did write from a hospital, but stated he was there on business. He might be wounded a dozen times, but he never would tell us about it."

(That article, by the way, was unkindly titled "Old Man Runs Away From Home to Fight." The

Ogden Standard also published Marie's comments under a different title.)

In 1916, Georges - now a Sergeant Major - was granted a leave of absence, and returned to Los Angeles. During his leave, he focused his energies on two important tasks: defending France from scapegoating, and raising funds for the wounded and maimed soldiers in his regiment. The French community and its supporters were very generous, and Georges was able to bring a good amount of money back to France when he rejoined his regiment.

Besides medals, Georges' leadership and courage earned him the praise of Generals Foch, Pershing, and de Castelnau. He was also appointed lieutenant flag bearer of the 106th Infantry.

As the war drew closer to an end, Georges - now a Lieutenant - was transferred to special duty under General Pershing. In this role, he acted as a liaison and translator for one of the French army divisions that trained with the American military. He led the Alsatian veterans when the army entered Strasbourg.

Georges told the

Ocala Evening Star "I couldn't remain quiet when the war broke out. Ever since 1871 I had itched to get back at the Germans...It was one of the happiest days of my life when the United States, my country, joined in the war against Germany on the side of the country of my birth."

While Georges was away fighting for France, his family founded the Le Mesnager Land and Water Company. They secured partial rights to the Verdugo Wash stream, which supplied water to the vineyard.

Georges returned to Los Angeles after the war ended. After four years of the war to end all wars (need I mention he was 68 when it ended?), he'd earned a well-deserved rest. But he had one thing left to do.

After returning to his home in Echo Park, Georges founded the Section Nivelle des Véterans Français de Los Angeles - a society for LA's French war veterans. He also served as its first president.

Finally, Georges decided it was time to retire. He bought a mansion in the Verdugo Hills called Sans Souci ("without a care" in French), which should not be confused with the Sans Souci fantasy castle in Hollywood.

In 1921, Georges was partially paralyzed by an apoplectic stroke. He knew it was the beginning of the end, and decided to spend his last days in France. The following year, he returned to Mayenne with Marie and Evon. Georges bought another grand property: the Chateau de Kerleón.

At six a.m. on September 6, 1923, Georges stood up and died in his nurse's arms.

Georges was buried with full military honors. Every war veterans' association flew its flag at the funeral. This being small-town France, the funeral was held before the very altar where he had been baptized so many years earlier. Colonel Oblet recorded Georges' considerable military accomplishments on his tombstone.

The Chateau de Kerleón was, tragically, destroyed by Nazi bombing in World War II.

Incredibly, the Le Mesnagers' old stone house is still standing at 3429 Markridge Road in Glendale and is being converted into a nature center. There is also a Mesnagers Street in Los Angeles.

Surviving sites associated with the French community are RARE (as of today, I've mapped FOUR HUNDRED, only a handful of which still exist). And yet, somehow, it doesn't seem like enough.

I, for one, would pay good money to see Georges Le Mesnager's story on the silver screen (and I can't sit through war movies).

*Most sources Anglicize Georges' name to George. Since older resources give his name as Georges, which is the correct form in French anyway, I'm calling him Georges.